The people's park

For generations, Itasca has been a sacred spot to Minnesotans.

© Beth Gauper

In Minnesota's early days, creating a park was no picnic.

As the public admired the towering pines around Lake Itasca, loggers dreamed of the miles of board feet they could produce.

"No measure was ever more unreasonably harassed and opposed," wrote park founder Jacob Brower. But in 1891, the Legislature gave the people their first state park by one vote.

Unfortunately, the loggers got most of the trees.

They might have done them all in if it hadn't been for people like 24-year-old Mary Gibbs, who in 1903 became North America's first female park commissioner after the death of her father.

That spring, with rising water threatening to swamp Itasca's pines, she asked loggers to open their dam gates to lower water levels, as required by law.

The armed superintendent threatened to shoot her if she put her hand on the levers, but she did anyway, famously declaring, "I will put my hand there, and you will not shoot it off, either."

Water levels went down, but soon logging lawyers got a court order to keep her away from the dam, and she resigned her post. Under the new park commissioner, logging around Itasca continued for another 14 years.

Things worked out in the end — that is, it's hard to imagine how the public could adore Itasca State Park any more than it already does.

"It's a memory maker," says Terri Dinesen, manager of another Minnesota state park who was visiting Itasca on her weekend off. "It's just one of those mile-marker, gotta-come-back kind of things."

Only the second state park in the nation, after Niagara Falls in New York, Itasca contains more than a quarter of the state's old-growth pines outside the Boundary Waters. That draws Minnesotans, who tramp through the groves inhaling the heady perfume of pine.

© Beth Gauper

But they also join the pilgrimage to the source of the Mississippi, which draws people from around the world.

A line of boulders marks the point at which the river trickles out of the lake and begins its 2,318-mile journey to the Gulf of Mexico, and few schoolchildren from Minnesota or anywhere else can resist picking their way across the boulders so they can shout, "I walked across the Mississippi!"

"I grew up thinking of it as a rite of passage, somewhere between baptism and confirmation," says Gene Merriam, former commissioner of Minnesota's Department of Natural Resources.

For many years, the headwaters was marked only by a 1930s plaque; now, there's also a center named for Mary Gibbs, with a restaurant, gift shop and plaza lined with exhibits, many featuring Gibbs' turn-of-the-century photographs.

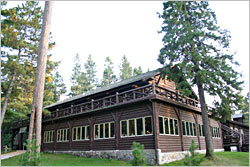

Almost from the beginning, Itasca was known as "Minnesota's Own Resort." Gibbs' last act as commissioner was ordering the logs for Douglas Lodge, a rustic but genteel hostelry that had its own post office until 1952.

Log guest cabins also were built, and people on a budget could stay at the Bear Paw Campground, which still holds the ice house where campers stocked their coolers with lake ice packed in sawdust.

Itasca is still Minnesota's own resort, the highlight of a summer. Of all Minnesota's state parks, it has by far the most overnight visitors.

Luckily, it takes just a weekend to see many of Itasca's highlights. Here are the top five.

Explore the headwaters

The new exhibits answer some perennial questions: Who discovered the true source of the Mississippi? Why was it so hard to find?

© Beth Gauper

After the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the U.S. needed to fix its western boundaries, so the race was on to find the start of the Mississippi. In 1798, English surveyor David Thompson claimed it was Turtle Lake, near Bemidji.

Lt. Zebulon Pike said it was Leech Lake, Lewis Cass said it was Cass Lake and Giacomo Beltrami said it was Lake Julia.

But a young man who had been on Cass' 1820 exhibition noticed that Cass Lake had two inlets, and in 1832, he returned to Cass Lake and asked an Ojibwe man named Ozawindib to lead him to the river's real source.

Henry Schoolcraft got the credit and concocted a name for the lake by putting together parts of two Latin words, verITAS CAput, or "true head."

But as one of the exhibits notes, Schoolcraft was simply one of the few explorers smart enough to ask someone who knew.

Even so, Schoolcraft's claim was disputed until 1888, when Jacob Brower was sent by the Minnesota Historical Society to survey the lake. A drought that year showed him that the five creeks flowing into Lake Itasca had nearly dried up, but the one flowing out stayed fairly constant.

© Beth Gauper

The direction in which the stream flowed had fooled everyone. From Itasca, the river flows north to Lake Bemidji, then heads east through Cass Lake and Lake Winnibigoshish.

"It's hard to convince people the river flows north," an Itasca naturalist said. "I've actually had people argue with me about it. It's a weird concept."

Early explorers also were fooled by the swamplike nature of the first 50 river miles; the river barely has a current after spring's high waters. Canoeists regularly get lost there.

Every year, canoeists, kayakers and bicyclists start cross-country treks at the head-waters; swimmers have made the trip at least once.

But most people at the headwaters are content to pick their way across the boulders that separate lake from river or to wade for a few yards through the pristine water.

Today, the channel is lined with grasses and wildflowers, and pebbles cover its bottom. This is a gussied-up version of the nascent Mississippi. In its natural state, it was a muddy swamp, before 1930s Civilian Conservation Corps crews revamped it with tons of rock and fill.

Cruise the lake on the Chester Charles

© Beth Gauper

Don't miss this narrated 1½-hour trip around the lake. Guides are savvy about nature and park history and have an unerring eye for wildlife, picking out loons, deer, herons and eagles for passengers to watch.

Our guide was Kim Coborn, who said passengers on 85 percent of her trips see bald eagles. As she drew the boat closer, an eagle hopped onto a downed tree, where it sat for a while before flapping away.

Eagles know a steady flow of tourists into the park means a ready source of roadkill, so they'll stick around until nearby farmers start to clear their fields and it's easier for them to find mice. "They're not a very ambitious bird," she said.

Interspersed with the steady narration is the Ojibwe point of view as well as Ojibwe words — migizi, eagle; shingobee, pine; manoomin, wild rice.

Passing the headwaters, which would have been hidden behind grasses in Schoolcraft's day, Coborn remarked on the agent's luck.

"If it hadn't been for Ozawindib and his people, Schoolcraft may never have found the source," she said. "You can no more say Schoolcraft discovered Itasca than you can say Christopher Columbus truly discovered America."

Ride around the park on a bike

© Beth Gauper

This is the best way to see the park and to get from one place to another. Five miles of twisting and rolling paved bike path follow the East Arm of Lake Itasca, past Douglas Lodge, Preachers Grove and through Bear Paw Campground.

On the North Arm, it passes the Pioneer Cemetery, the beach and the 1893 ruins and replica of Theodore Wegmann's cabin and general store, where the early settler sold postcards, candy and ice cream to tourists.

Passing the headwaters, the path joins Wilderness Drive, which soon becomes one-way. Gliding under a canopy of trees, cyclists can stop to see the largest white pine and the largest red pine, as well as hike half a mile to Bohall Lake.

Near the end of the drive, a half-mile gravel path leads to the Aiton Heights Fire Tower, which takes climbers above the treetops.

The loop is 17 miles, a great way to spend an afternoon. Itasca Sports Rentals supplies very nice mountain bikes from its spot on the lake, near the beach.

Be careful when many people, especially children, are using the bike path, whose ups and downs often obscure oncoming traffic.

Hike the trails

© Beth Gauper

From the headwaters, the mile-long Schoolcraft Trail follows the other side of the North Arm, ending at Hill Point, where a timber fence protects an Ojibwe cemetery.

From the point, hikers can gaze upon Schoolcraft Island, where, on his short but fateful trip to the lake, the Indian agent had lunch, put up a flag and hurried off to fulfill the official purpose of his visit, which included vaccinating Ojibwe children for smallpox.

To get a sense for what northern Minnesota was like before the loggers came, hike the half-mile Bohall Trail to Bohall Lake, off Wilderness Drive. There are more giant pines along the Nicollet Trail, which starts off Wilderness Drive near Elk Lake.

The most popular trail is the Dr. Roberts Nature Trail, which starts from the lakeshore at the foot of Douglas Lodge. It's a two-mile loop, first passing across a bog on its way to the Old-Timer's Cabin, which a CCC crew built with four giant logs in the winter of 1933-34.

In spring, hikers can spot showy lady's-slippers along the trail, where special features are marked by numbers explained in a take-along guide.

Visit the Jacob V. Brower Visitors Center

This handsome center near the south entrance is filled with all kinds of park memorabilia.

There's the Douglas Lodge's lady's-slipper china and its original guest book, with such comments as a 1924 entry: "For one who sees nothing but cornfields, the pines are a wonderful treat."

The famous standoff at the dam site is chronicled, with a letter of support to Gibbs from the aging Jacob Brower: "I sincerely hope the reports in the papers concerning your energetic defense of the beauties of Itasca Park are correct . . . Someone ought to assert the rights of the state against such threatened destruction as has been attempted."

There's an Ojibwe birchbark lodge and a canvas tent with early camping supplies. There's an exhibit on the 1930s CCC camps, whose crews built roads, planted trees and stocked fish, and the VCC crew of veterans who built the stone Forest Inn.

On one wall, an electronic quiz asks visitors what determines the beginning of the river.

Most, it turns out, agree with Joseph Nicollet, who thought that a river begins at the farthest point upstream where the first drop of water flows, rather than with Henry Schoolcraft and Jacob Brower, who thought it was the farthest point upstream where the flow first constitutes a river.

In Itasca, there's always room for argument.

Trip Tips: Lake Itasca State Park in northern Minnesota

© Beth Gauper

Getting there: It's 3½ to 4 hours north of the Twin Cities.

*Events: Check for lantern-lit ski, snowshoe and hiking evenings, concerts and other naturalist programs.

When to go: The park is at its best in every season. Hiking is best in fall, when bugs are down and leaves change color. Look for peak maple-basswood-birch colors this week and peak oak-aspen colors between the first and second weeks of October.

It's just as lovely in winter, when pine boughs are draped in snow and 13 miles of trails are groomed for skiing.

For more, see Itasca in winter.

In spring, orchids and other wildflowers bloom along trails.

Sports rental : By the boat landing, Itasca Sports rents canoes, kayaks, bikes, paddleboats and pontoon boats, and it sells fishing tackle, snacks and basic camping goods.

Cruises: Coborn's Lake Itasca Tours are held from Memorial Day weekend through the first week of October.

© Lauren Gagner

Accommodations: Except for the Four-Season Suites, the Headwaters Inn and five Bert's Cabins that stay open for the November deer-hunting season, park lodgings in the park close in October.

Lodging reservations for park lodgings can be made 120 days in advance at 866-857-2757.

Campsite reservations in Itasca are among the hardest to get, after Split Rock, Temperance River and Tettegouche state parks. However, some of Itasca's campsites are designated first-come, first-served.

The best bet in winter are the 12 two-room Four-Season Suites, near Douglas Lodge in two buildings that sit on either side of a large asphalt parking lot.

There's no view, but the suites are attractively furnished and have cable TV, kitchenettes, WiFi and screened, concrete-floored porches.

The log Headwaters Inn on Lake Itasca, the former park headquarters and then a Hostelling International hostel, now is operated by the park and offers six bedrooms with full beds, $85. Guests share three bathrooms, a large kitchen, dining room and great room with a stone wood-burning fireplace.

The 1905 Douglas Lodge has suites and rooms with shared baths. The 1910 Clubhouse has 10 bedrooms. The two-bedroom Historic East Cabin has a fireplace, heat and air-conditioning.

The very popular Itasca Ozawindib Lake Cabin sleeps up to eight; bring bedding.

Housekeeping cabins sleep four and have a toilet but no shower, $103. Cabins of various sizes come without kitchens, but some have fireplace and screened porch.

© Beth Gauper

Group lodgings include the 10-bedroom, six-bath Clubhouse, which sleeps 21 and has a fireplace and screened porch overlooking Lake Itasca but no kitchen.

The Lake Ozawindib group center of up to 75 includes a large dining hall, a counselor cabin that sleeps five and a shower building.

A mile from the headwaters, on Wilderness Drive, the park also operates Bert's Cabins, a collection of 12 log housekeeping cabins in a lovely grove of red pines.

Seven of the cabins are open from Memorial Day weekend through the first week of October, and five are open from the fishing opener in May through the second weekend of deer firearms season in November.

Dining: Douglas Lodge is a very pleasant place to have a meal. It's best to stick to basics - the burgers, the salad bar, the roast pork or turkey dinners.

For lunch, eat in the cafeteria of the Mary Gibbs Mississippi Headwaters Center, which serves sandwiches, soups and desserts.

Information: Itasca State Park, 218-266-2100.