A jumpin' joint

A Norwegian village in southwest Wisconsin has a longtime love affair with ski jumping.

© Beth Gauper

In Westby, Norwegians take their love of tradition to extreme heights.

The high ridges and deep coulees south of La Crosse drew so many Norwegian immigrants in the 19th century that the area around Westby became known as "America's little Gudbrandsdal," after the valley in Norway.

The Norwegians had left their homes, but not their customs. Today, Norwegian flags fly from lampposts, and the visitors center is a stabbur, a top-heavy wood building used in Norway since the Middle Ages.

In May, the trolls and folk costumes come out for the annual celebration of Syttende Mai, the Norwegian constitution day. Norwegian-Americans and even Norwegians from Norway seek out its imports store.

"They say, 'Oh, you have it all, you have the real Norway here,' " says Jana Dregne of Dregne's Scandinavian Gifts.

One tradition is a lot harder to maintain, but the folks of Westby have done it for a century. The town has only 2,000 people, but in February, it puts on a ski-jumping tournament that draws athletes from around the nation to its carefully groomed Olympic-size hill.

It's one of only a few in the United States: Park City, Lake Placid, Steamboat Springs . . . and then there's little Westby.

"The hard-core guys get together and just start working," said Randy Mikkelson, manager of the Snowflake Ski Club clubhouse.

In the summer, they make sure the hill's dimensions are just so. In the winter, they draw water from a well at the top of the hill and cover it with artificial snow, better than natural snow because it's denser, cleaner and resists melting.

Then the whole town turns out for the tournament in February, turning the flat floor of Timber Coulee into a big tailgate party. People sit in chairs around bonfires, grilling bratwurst. The mayor gives a speech. The local princesses speak. Children are set loose on a snow pile spiked with money.

It's a typical small-town festival. And then the jumping starts.

I've never been to a Winter Olympics, but I'm pretty sure you can't watch from the top of the jump. You can in Westby.

You can walk right up and watch as the young athletes hurl themselves off a scaffold and down the 118-meter hill, the equivalent of jumping off a 41-story skyscraper.

It's quite a sight, the parade of neon-suited jumpers flying by at 55 mph, but it's the sound that's so mesmerizing: When a jumper picks just the right moment to take off, snapping from a crouch into a nearly horizontal V, the resulting thwump of air against gut is like the buzz of a giant, very angry bumblebee.

© Beth Gauper

"Whoa, what a wicked sound," said a man watching near me.

Skiers from Austria, Slovenia, Ukraine, Finland, Sweden, Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic and Norway have competed.

When Westby was a stop on the Continental Cup circuit, the town paid half their travel expenses, splitting them with Iron Mountain, Mich., just over the Wisconsin border, to which the skiers go next for a tournament on its 133-meter hill.

Skiers stay the week with local families, and by tournament time, they've got a ready-made cheering section. Andrea Eitland had hosted the Czech team for six years and called them "our guys."

"We get so attached to them, we usually cry when they leave," she said.

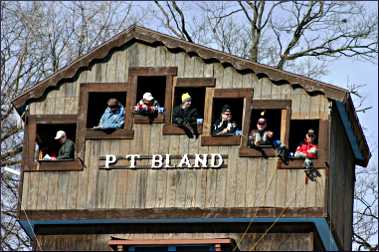

The view is magnificent from the top, but on cold days many spectators stay in their cars, honking wildly after good jumps. Judges watch from the seven windows of the stabbur on the side of the hill, evaluating style and grace, and markers measure distance.

After the skiers land and glide out of the chute, the Snowflake princesses run up to get photos of themselves with the skiers — the cute ones, anyway.

The year I went, two Olympians were jumping with the U.S. Ski Team. There was triumph, as a Slovenian set a hill record.

And there was humiliation, when skiers botched their landings and sank to their knees, cradling their heads in disgust.

But there weren't a lot of people to see it. Fifty years ago, the event drew 20,000 spectators; now, it's down to 3,000.

"When I grew up, you would not even think of coming in to park a vehicle, because there were so many people you could hardly find standing room," said NanJean Hoff of Windsor, Wis., who came wearing a vintage raccoon coat that stood out amid the parkas and camouflage jackets.

"We have world-class skiers coming; why would you not come down and watch them? I just think it's a treasure."

© Beth Gauper

But ski-jumping is an expensive sport, and young Americans have other things to do. Westby hasn't had a jumper of its own for years.

Westby physician P.T. Bland, who perhaps had done more than anyone to maintain Westby's place in the ski-jumping firmament, was 84 that year and watching from a warm truck.

"It'll come around," he said. "We've got the Norwegian heritage, we've got the hills, you can't find a better place. This is what we do. Westby is identified with ski jumping."

Bland became a world-renowned ski-hill designer by accident, after a Norwegian visited in 1967 and saw that skiers were flying too high.

"He said, 'Your hill is bad, you have to learn how to fix it,' " Bland said. "So I went to Norway and talked to this crusty old guy, and I said, 'Why don't you write a book about designing ski hills?' and he said, 'Doctor, why don't you write a book about being a doctor?' " Bland persisted, learned hill-design mechanics and went on to consult around the world and chair the U.S. Ski Association jump-design committee for two decades.

"I'm not Norwegian, I've never jumped, but I'm your man for ski hills," he said.

© Beth Gauper

As the afternoon waned, shadows crept toward the hill and men in crampons climbed up to place pine boughs around the K point, easier for skiers to see than the spray-painted red lines that show where the hill begins to flatten out.

After the last skier had jumped, the unofficial winners were announced, and a cannon at the bottom of the hill was fired twice. The German coach caught it all with his camcorder and shook his head, muttering, "This is crazy."

Anyone who comes for the tournament should check out the town, too. I'd go back just for the truly excellent Valentine's sweetheart cookies from the Westby bakery,; after I tasted them, I went back for another dozen.

It was the same story at the Westby Cooperative Creamery, founded in 1903: I went in for aged Cheddar and came out with three pounds of especially good Amish cashew crunch from Hidden Ridge Farm.

You can get a cappuccino at the sunny espresso bar of the Westby Pharmacy and shop for imported goods at Dregne's. In Poplar Coulee, west of Timber Coulee, there's snowshoeing on five miles of trails at Norskedalen Nature and Heritage Center, which has a visitor center, arboretum and restored Norwegian pioneer homestead to explore.

The coulees are beautiful in winter, when shifting shadows highlight their sinuous, snow-covered curves. It's easy to see why the Norwegians loved these tucked-away valleys, so well-suited for their favorite sport.

"Wherever you live in the world, you've got to take something out of it," said P.T. Bland, the honorary Norwegian. "The tournament is a great prescription for the community. Plus, it's a lot of fun."

Trip Tips: Westby, Wisconsin

Getting there: La Crosse is three hours from St. Paul; Westby is another half-hour.

To get to Timber Coulee, take Wisconsin 27 north from Westby, then County Road P west.

Snowflake Ski-Jumping Competition: It's the first weekend in February. Pork sandwiches, brats and other food are sold at the hill.

Accommodations: The Westby House B&B, just off main street, is an 1890s Victorian and adjacent guest house with seven rooms and suites.

Norskedalen rents its 1870s Per and Anna Paulsen Cabin for two-night weekends for up to six. It has a full kitchen and remodeled bathroom.

Twenty minutes west of Westby on U.S. 14/61, near La Crosse, the Wilson Schoolhouse Inn is a beautifully restored 1917 schoolhouse with a lavishly equipped kitchen, two bedrooms and two bathrooms. It has a queen, two twins and two pull-out sofas.

Norskedalen: This open-air heritage museum is three miles north of Coon Valley off County Road P and open daily in winter except the second and fourth Saturdays; from May through October, there are guided tours.

Ski jumping elsewhere: Many of the Westby skiers go on to compete in Iron Mountain, Mich., just over the Wisconsin border. The Continental Cup tournament at the 133-meter Pine Mountain jump also is a great spectator event.

Information: Westby tourism.

For more about the area and the people who settled in it, see Valleys of Vernon County.