Life on Mille Lacs

Minnesota's big lake is a capital of both walleyes and Ojibwe culture.

© Beth Gauper

Big Mille Lacs is up north, but it isn't a wilderness lake. It's more like a big pond, its vast surfaces dotted with powerboats, its depths thoroughly probed.

A highway rings its 100 miles of shore, the better for boat access. Its air is laced with the perfume of gasoline, minnows and frying oil; the lake wouldn't be known as the Walleye Factory if it weren't.

But fishermen arrived only recently. Woodland tribes were the first to thrive on its shores.

When French explorers arrived, the Dakota were living there; by the mid-1700s, they had been replaced by the Ojibwe.

The Ojibwe hung onto the land after Europeans arrived, earning themselves the name "Non-Removables." Now, they celebrate their heritage at the splendid Mille Lacs Indian Museum and at the biggest event of the year, a traditional powwow in August.

Their predecessors, the Dakota, called themselves "the people who live by the water of the Great Spirit." French fur traders renamed their Spirit Lake, calling it Mille Lacs, or 1,000 Lakes, referring to the whole region.

The French also mistranslated the Spirit Water, or Mde Wakan, that flowed from the lake, calling it the Rum River.

This Dakota band, the Mdewakanton, fished for walleye and pike, hunted in the rolling, wooded hills and tapped maples for their sugar.

There was wild rice in the marshes and smaller lakes; when the people learned to parch green rice for storage, around 800 A.D., they began to establish year-round villages.

At the largest village, Izatys, explorer Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut, planted the French arms in 1679.

The Ojibwe arrived in the 1700s and, according to their oral tradition, forced the Dakota out of northern Minnesota in an epic 1745 battle. The Ojibwe spent the next two centuries trying to hang onto the land, as white loggers and settlers made their own claims.

Today, they share the shoreline with fishermen, who claim their own spiritual connection to this 20- by 14-mile lake, affectionately known as the walleye factory.

In the spring and summer, armadas of small boats make the bays look like the beaches of Normandy. In the winter, more than 5,000 icehouses pop up, forming a village known as Frostbite Flats.

© Beth Gauper

Here, fishing is a way of life. The shore is lined with giant fiberglass walleyes, boat launches, ma-and-pa resorts and shacks advertising Bait-Gas-Grocery — the true essentials of life on Mille Lacs.

Tiny Garrison is the nominal capital, with its motels, restaurants and 15-foot walleye at water's edge.

Ojibwe land starts to the south, past Wigwam Bay. Into the 1950s, local Ojibwe stationed themselves along the road in summer, making a meager living by selling handmade baskets, blueberries and souvenirs to tourists, displaying their wares on lines running between trees.

They're still making a living from tourists, but now their source of income is the Grand Casino Mille Lacs, which lights the night sky from a hill above the highway.

The casino, which includes a hotel and restaurants, has earned millions, which the band has plowed into tribal schools, clinics and roads in the spirit of shawanima, the common good.

Across the road, Ojibwe culture is preserved and displayed at the Mille Lacs Indian Museum, run by the Minnesota Historical Society in cooperation with the Mille Lacs band.

Ojibwe artisans often work at the museum, demonstrating the arts of beading, sweetgrass basketry or flute-making. Videos show fancy dancers at powwows and wild-ricers thwacking the grain into canoes.

A computer that translates English words into the soft, cushioned syllables of Ojibwe is a huge draw for children, who watch, fascinated, as it turns "candy" into ziinzibaakewadooz(n)s and "blueberry pie" into miinan, for blueberries, and another 85 letters that explain how the pie is made.

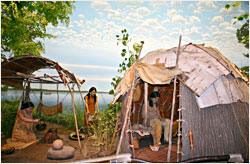

But the Four Seasons room is the centerpiece. Life-size figures enact the seasonal cycle, tapping and stirring syrup over a fire in the spring sugaring camp and making nets of stinging nettles in the summer fishing wigwam.

They gathered and parched rice in the fall wild-rice camp, and carved pipes and mended inside the winter tipi, insulated with cattail mats and banked in snow and leaves.

Overhead, geese honk and owls call according to the season. Guides, some of whose relatives were the models for the figures, tell about Ojibwe innovations, from early wildlife conservation to the first disposable diapers, lined with dry moss and completely biodegradable.

© Beth Gauper

The museum also includes exquisite examples of Ojibwe artistry — birchbark tobacco trays, basswood boxes, beaded bandolier bags — many from the collection of Harry and Jeannette Ayer, who ran a trading post on the reservation from 1918 to 1959.

Next door, their restored 1925 Trading Post now is the museum gift shop, with contemporary craftwork for sale.

Three miles farther south on U.S. 169, clusters of campers' tents at Mille Lacs-Kathio State Park echo the many wigwams that once stood here.

The park — Kathio is a corrupted version of Izatys — straddles the Rum River as it begins its twisting run down to the Mississippi, and remnants of villages from 800 A.D. have been found along Ogechie, Shakopee and Onamia lakes, through which it runs.

On Ogechie, the park has re-created a palisaded village from traces found in one place, one of 19 prehistoric sites in the park.

In 1680, Father Louis Hennepin spent six months here with the Dakota, who found him and members of his expedition while they were camping on Lake Pepin. He spent the time taking notes for an adventure book, which became a best-seller in France.

© Beth Gauper

Today, hikers and skiers flock to the state park, Minnesota's fourth-largest. It has 35 miles of hiking trails, but it really becomes a playground in winter, when skiers head out on 20 miles of tracked cross-country trails.

Snowmobilers have 19 miles of groomed track, nearly all at a healthy remove from the ski trails. There's a popular sledding and tubing hill just outside the parks trail center, where logs crackle merrily on a raised round hearth.

Its annual candlelight ski, when volunteers set out more than 400 luminaries along 3¼ miles of trails, is one of the best-attended events in Minnesota parks. Hundreds of people show up to glide through bogs and glens, given a fairy-tale aura by the glowing bags.

The 11-mile, paved Soo Line Trail connects Mille Lacs Kathio to Father Hennepin State Park, just outside the town of Isle on the lake's southeast corner.

It's a smaller park, but its shady lakefront campsites, within earshot of the lapping water, are highly prized. Boat access and a long swimming beach are just steps away.

Isle is at the lake's southeast corner, where another fiberglass walleye proclaims "The Walleye Capital of the World." It's a claim that's not refuted around here.

Trip Tips: Mille Lacs Lake in Minnesota

Getting there: It's 20 miles east of Brainerd and 100 miles north of the Twin Cities on U.S. 169.

Powwows: The Mille Lacs Indian Museum holds a powwow on Memorial Day, and the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe traditional powwow is in August.

The public is welcomed. For tips on protocol, see Powwow primer.

For more, see Heritage travel: Dakota and Ojibwe and Ojibwe or Chippewa, Dakota or Sioux?

Mille Lacs Indian Museum: It's three miles north of the park on U.S. 169. Demonstrations and classes are held on weekends. Admission is $10, $8 for children ages 5-17. No admission is required at the trading post.

Mille Lacs-Kathio State Park: This large camping park is eight miles north of Onamia on the southwest corner of the lake, a half-mile off 169 on Minnesota 26. It has an interpretive center and many naturalist activities, especially in archery, fishing and canoeing.

There's a swimming beach and rental of canoes, kayaks and rowboats for paddling on the Rum River and Ogechie and Shakopee lakes.

The park also is a popular winter destination, with 20 miles of groomed cross-country skiing trails and a sledding hill with warming house.

© Beth Gauper

Father Hennepin State Park: This small park occupies a point just west of Isle and has a large swimming beach, fishing piers, hiking trails and campgrounds.

Bicycling: The paved, 11-mile Mille Lacs Soo Line Trail cuts through countryside on Mille Lacs' south shore, between the old depot behind Onamia's Main Street to the playing field in Isle.

Unfortunately, riders on the adjoining ATV trail spew gravel and rocks, some of them palm-size, onto the trail.

From Onamia, it's a six-mile ride on County Road 26/27 to Mille Lacs-Kathio State Park. In Isle, Father Hennepin State Park adjoins the town, and riders can use its beautiful lakeside trails and beach.

Accommodations: The large Grand Casino Mille Lacs Hotel is across the highway from the museum and has restaurants and an indoor pool with large whirlpool spa.

Mille Lacs Kathio State Park rents five year-round camper cabins, one of them handicapped-accessible.

In Garrison, the Garrison Inn & Suites has an indoor pool.

There are many lakeside resorts. Two of the larger ones that cater to fishermen and snowmobilers are Eddy's Lake Mille Lacs Resort, a half-mile from Kathio, and McQuoid's Inn east of Isle, with motel rooms, cabins and condos.

Izatys Resort, on the south shore, is centered on two 18-hole golf courses and a full-service marina. Ask for package specials. There are indoor and outdoor pools and a supervised children's program.

The best place for families on a budget is Camp Onomia, a Lutheran retreat center with an indoor pool and two saunas that's four miles south of Mille Lacs-Kathio on Minnesota 26.

It caters to groups and is in high demand for family reunions. But rooms, all with private bath, may be available to individual families on weekends. Bedding and towels are not provided but can rented.

Nightlife: Grand Casino Mille Lacs frequently presents nationally known performers in concert.

Information: Mille Lacs tourism, 888-350-2692.