Minnesota's Boundary Waters

For canoeists, this vast wilderness is the promised land.

© Lauren Gagner

Along Minnesota's northern border with Canada, more than 200,000 people a year find an increasingly rare commodity — absolute wilderness.

The million-acre Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness is barely changed since voyageurs used its chain of lakes and rivers to push deep into the continent's interior.

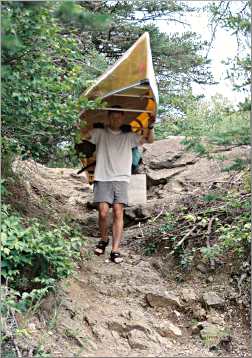

Today, the foot trails over which they carried canoes and 180-pound packs are used by vacationers, who wind their way from lake to lake in search of the perfect combination of woods, water and solitude.

As they paddle along the glassy waters of more than 1,000 lakes, they may see moose, lynx, otters and beaver, who have rebounded from near-extinction at the hands of trappers.

In the evening, at nearly 2,200 campsites, they listen for the trill of loons and the howl of wolves, whose numbers also have rebounded.

It's the stuff of memories, to be fondly savored back in civilization.

To people who consider the Midwest flyover land, the BWCA puts Minnesota on the map. National Geographic Traveler listed it as one of 50 Places of a Lifetime/The World's Greatest Destinations, along with the Grand Canyon and Big Sur.

In the book "1,000 Places to See Before You Die," it's the only Minnesota entry.

Whenever I travel outside the Midwest, people I meet always scan their brains for whatever they know about Minnesota, then ask, "Have you been to the Boundary Waters?"

When I finally took a week to paddle there, I was surprised. The portages I'd imagined as grassy paths through the forest were muddy up-and-down trails studded with boulders and choked with tree roots; the first day, we carried our gear over nearly two miles of them.

And once we were at the campsite, everything took a lot of time — filtering water, washing dishes off in the woods, protecting food from the chipmunk we knew was lurking and any bear that might be.

Being in the Boundary Waters is work. But there's no place better.

Some people love the BWCA for its solitude, some for its scenery. As it turned out, I loved the water.

Once I realized I could swim anywhere, any time, I took to the black, glassy water, sometimes floating motionlessly to watch loons, sometimes diving underwater to feel the rush of cool, clean water along my skin.

There are few weeds here, because there is so little soil. Glaciers ground up the softer rock and carried it down to Iowa.

What's left is a stripped-down landscape of sky, spruce and outcroppings of greenstone and granite, among the hardest and oldest rock on Earth.

© Beth Gauper

All that rock and water create acoustics worthy of an orchestra hall. We could hear every ringing note of loon calls; over the week, we heard their whole lexicon, and wished desperately for a dictionary.

We heard the howls of wolves on one side of lake, and the answers from the other. When people a mile away started singing and playing a guitar, we could pick out words.

The Boundary Waters are serene, but hardly silent. At night, the sawing of crickets provides white noise, along with the steady squeaking of bark beetles and the whine of mosquitoes, revving up like tiny Harleys.

One evening, while we were eating dinner under clear skies, we heard a hum, like faraway traffic, and looked up. It grew louder, but we saw nothing; then, a wall of mist rounded the corner of the next bay like a horizontal waterfall.

As we watched, puzzled, a few drops fell on our heads, and the skies opened. Twenty minutes later, we got a rainbow.

People sometimes make fewer appearances than wildlife, sometimes more. When we paddled onto Tuscarora Lake, the first eight campsites were occupied, but we saw only an occasional far-off canoe until the last day, when a canoe came to explore our bay.

We saw more people the day we canoed through four small lakes on our way to Little Saganaga, but not many: two fishermen in the shadows of Saganaga's cliffs, a family playing on the rapids between Crooked and Tarry lakes.

We met the family a day later, during a sudden downpour on the Owl Lake portage. They hadn't looked like typical BWCA types, in their baggy T-shirts and cotton pants, but Rick and Elaine Wrack of Avon, Minn., had been coming every year for 30 years.

"We met on a high-school trip to the BWCA, and we've been coming here ever since," Rick Wrack said. "And I'll keep coming till my bones are creaking."

"And then we'll have to drag them here," added their 12-year-old nephew, Tim Marshall of Laporte, Minn.

They'd also been in the BWCA during the deadly blow-down of 1999, Elaine Wrack said. "So this is nothing, just a little water," she said, cheerfully stuffing her pack as the rain soaked her clothes.

There is, of course, no typical BWCA visitor. The first person we saw, on the portage to Tuscarora, was wearing a birchbark top hat.

The last people we saw were teen-age girls shrieking and bobbing atop the water, wearing their life vests "like diapers," they told us when we asked.

There's not really a "right" way to be in the Boundary Waters. Torsten and I packed ultra light, bringing only some dried apricots for a treat. But after I got back, a friend of my niece's told me about a different approach.

She'd been to the Boundary Waters that month, too, but she and her six girlfriends had carried in foam fun noodles, blow-up rafts, boxed wine and Bop-It electronic party games. They were particularly glad, she said, to have the rafts.

Next time, I'm bringing chocolate bars.

© Beth Gauper

Planning a trip

The easiest way for a beginner to go to the Boundary Waters is with a group or a friend who has good gear to share — lightweight tent, stove and water filter, in addition to the lightweight sleeping bag, sleeping pad, Duluth pack and Nalgene bottles you'll each need.

We own a good fiberglass canoe, but we splurged and rented a lightweight Kevlar canoe that turned out to be a godsend on the grueling, 1½-mile Tuscarora portage, which we did in a single trip — 40 minutes, compared with the two hours it took two men we met.

It's even easier to drive up to Ely or the North Shore with a credit card and let someone else take care of everything.

"Unless you go in with someone who has all the gear, I'd say spend the money to go with an outfitter," says wilderness expert Tom Kaffine. "They are pricey, but they'll let you know if you like it or not, before you buy all the gear."

The thing that makes the Boundary Waters truly egalitarian, however, is that it doesn't cost anything to be there, beyond the permit. Gear doesn't have to be expensive. And trips needn't be backbreaking treks deep into the interior.

The Friends of the Boundary Waters suggests seven two-day routes that are good introductions to canoe camping in the BWCAW. And here are six good five-day routes.

Some people, like my niece's friend, make just one short portage and then set up a base camp.

Those people, however, sacrifice solitude and privacy, and it can be hard to find a campsite.

There's a lot to consider when planning a BWCA trip. Luckily, there are dozens of guidebooks and plenty of people willing to give advice at outdoors and sporting goods stores.

The Friends of the Boundary Waters offer a step-by-step planning guide.

At the U.S. Forest Service stations in Tofte, Grand Marais, Ely and Cook, rangers are good sources of advice.

They'll supply handy tips on gear, suggesting things many canoeists don't think about bringing, such as a collapsible wash basin, an extra paddle and boots for portages.

They also give safety tips. Rangers often are concerned about fire danger created by dead stumps from blow-downs.

January is the time to reserve a permit if you're on your own and want to use one of the more popular entry points — that is, one near the shortest and easiest portages that lead to the largest variety of lakes.

But if you can't plan that far ahead, don't worry. We didn't get our permit until two weeks before we left in August, and we ended up with a secluded campsite on a beautiful lake. And outfitters always have plenty of permits for their customers.

The important thing is to go out and get your feet wet.

Trip Tips: Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness

When to go: Early June generally is the height of black-fly season, depending on how early spring arrives. Bring hats with netting, available at outfitters.

July and August are peak season, but expect some bugs. May and September can be sunny and warm or it can snow; anything is possible.

Who can go: Nine people and four watercraft are the maximum allowed per party.

Camping: It's first-come, first-served, and allowed only at designated sites, which have fire grates and wilderness latrines.

© Beth Gauper

Entry points: There are 64 overnight-entry points from the perimeter of the BWCA, including the North Shore, the Gunflint Trail, Ely and the Lake Vermilion area.

Routes: Possibilities are endless. The Friends of the Boundary Waters suggest these four loops, and also offers a trip-planning tool.

Making a reservation: Reserve early for the best choice of entry permits into the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. For stays between May 1 and Sept. 30, entry permits can be reserved, first-come, first-served, starting the last Wednesday of January at Recreation. gov, 877-444-6777.

You may want to list alternate leaders on your permit, so others can pick them up if needed.

Fees: The non-refundable reservation fee is $6 for overnight trips as well as day-use motorized trips to designated lakes.

Per-person, per-trip user fees are $16, $8 for children to age 17.

Getting a permit: They can be picked up at 70 resorts, outfitters, YMCA camps, bait shops and Forest Service offices, as specified by the person making the reservation.

These stations also issue non-reserved permits, if available. Credit cards are required for balance due; only Forest Service offices can accept cash and checks.

Self-issuing permits: Forms for day use or overnight trips between Oct. 1 and April 30 can be picked up at main entry points, at outfitters and Superior National Forest offices and by mail. Carry a copy during the trip.

Maps: You'll need to carry a map. They're available from outfitters or from the W.A. Fisher Co, 218-741-9544, or McKenzie Maps, 800-749-2113.

What to bring: Browse in outdoors stores for the basics: lightweight tent, stove, water filter, sleeping bag, sleeping pad, pack and Nalgene bottles.

The Piragis Boundary Waters catalog out of Ely shows all kinds of goodies and dozens of books.

Outfitters: Contact Ely, 800-777-7281, or Cook County (Tofte area and Gunflint Trail), 218-387-2524.

Information: See the U.S. Forest Service's BWCAW Trip Planning Guide or call 218-626-4300 for a copy.