Paddling the Chicago River

After years of neglect, this urban waterway has become a place to play.

© Beth Gauper

The Chicago River never has run clear.

Before settlers arrived, it was a lethargic prairie river that ran through a swamp the Potawatomi called Checaugou — for "swamp weed," or "wild onion."

Then factories and slaughterhouses turned it into a sewer. At the confluence of the main branch with the north and south branches, Bubbly Creek was named for the methane gas that rose from decomposing carcasses on the river bottom.

When it fouled Lake Michigan, source of the city's drinking water, city officials reversed the river and sent Chicago's filth to Peoria.

But in the 1980s, after being dredged, straightened, dumped on and dyed, the Chicago River finally started getting some respect — and a much-needed cleaning.

Now, sightseeing excursions ferry tourists past downtown landmarks, and architecture cruises are packed with rubberneckers.

Water taxis take commuters and tourists to Chinatown and the Willis Tower. Yachts and sailboats glide out of the marinas of South Branch condos and boat clubs, vying for space with barges and, increasingly, canoes and kayaks.

One year, I got in a canoe myself, joining a Friends of the Chicago River expedition.

The group champions the river's 156 miles and reasons that, if people would just get out on the river, they'll grow to love it and want to protect it.

It's worked; the organization now has thousands of members and volunteers, including former Minnesotan Mark Sorteberg.

"Growing up near the Rum River, I never thought of canoeing; it was just something you did with six or eight other guys and a case of beer, zigzagging all around," said Sorteberg, a volunteer weekend guide. "Then I came on a tour just like this one, and I became a river groupie."

Today, he doesn't mind paddling through a landscape filled by skyscrapers rather than trees: "You've seen one tree, you've seen 'em all," he joked.

© Beth Gauper

In a flotilla of 14 canoes, we left from the Ogden Slip, once a loading dock in the world's fourth busiest port and now an upscale neighborhood of townhouses and cafes.

We paddled past Navy Pier and the locks that limit the flow of Lake Michigan into the river; the city had been quickening the river's flow by adding lake water but had to stop when it was sued by surrounding states in the 1920s.

Once on the main branch, we glided under the Lake Shore Drive bridge, its deck crowded with bicyclists and walkers, and past Centennial Fountain, whose water cannon shot off across the water just behind us.

People were strolling along the banks on the Riverwalk; in 1990, the City Council began requiring new buildings to sit at least 30 feet from the river, to allow space for a public walkway.

Soon one of the most famous vistas in Chicago opened up before us: the neo-Gothic Tribune Tower, Wrigley Building and other buildings that cluster around the Michigan Avenue bridge. At State Street, two sailboats were waiting; as we passed, half of the bridge opened to let them through.

At Wolf Point, named not for wildlife but for a tavern, we reached the confluence of the main branch with the north and south branches and infamous Bubbly Creek.

The Chicago River wasn't much of a river, but when a canal connected it to the Des Plaines River in 1848, it became the critical link between the East Coast and the Mississippi, what tour guides call "the golden funnel."

A great city grew, and factories and slaughterhouses found it convenient to throw waste and carcasses into the river. In his 1906 expose "The Jungle," Upton Sinclair described spots where "the grease and filth have caked solid, and the creek looks like a bed of lava."

That's what flowed into Lake Michigan, from which the city drew its drinking water. Typhoid and cholera killed thousands, and in 1885, after heavy rains washed human sewage into the lake, more than 90,000 people died within days.

Finally, city officials dealt with the problem — by reversing the river.

With their effluent now flowing toward Peoria and St. Louis, Chicagoans felt little urgency to clean up the river. It was ignored until the early 1980s, when the city, prodded by the newly formed Friends of the Chicago River, started to take action.

Chicago's official flag, ironically, pays tribute to the river: Its two light-blue stripes represent the north and south branches of the Chicago River. Of course, the river never has been blue.

Today, it's teal green, but clean enough that kingfishers and turtles live alongside it, as well as fish that even, according to the EPA, can be eaten once a month.

© Beth Gauper

Once we had paddled past the art-nouveau Civic Opera House, the Merchandise Mart, Willis Tower and other skyscrapers along the South Branch, we turned our heads back for a view of the city, an island of glass and steel now framed by green.

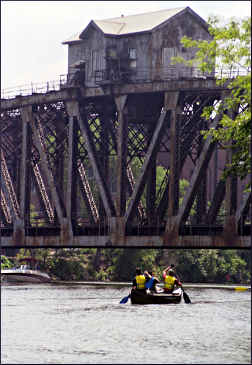

We had lunch on a grassy bank across from the Amtrak service center, just upriver from an enormous twin trestle bridge, one of them reared back onto a tangle of metal that was as artful as a Louise Nevelson sculpture.

There's a certain beauty in industrial architecture — in the mysterious nuts, bolts pipes and cranks of the Fisk Generating Station; in a nifty little guardhouse suspended over the water next to an old plastic factory; in the heavy trunnion bascule bridges.

The bridges rise like a seesaw — bascule is French for seesaw — while pivoting on an axle, or trunnion; they're so finely balanced only a small motor is needed to lift them.

I saw a family of geese paddling near a clump of wild yellow iris, and mallards sitting next to a concrete retaining wall, covered by a lacy tangle of pink crown vetch.

There was only one patch of litter, just down from the South Branch Marina; wind brings much of it, especially plastic bags.

Then we passed Ping Tom Memorial Park, with its big red-and-yellow pagoda, and cruised into Bridgeport, a working-class neighborhood that was home to the Daleys and three other mayors from 1933-1979 and 1989-2011.

The North Branch, which heads north through parks and forest preserves, is more scenic: "You have no clue you're in a metro area with a million people within two miles," says guide Karen Harrer.

Sorteberg, however, prefers the industrial South Branch: "I think for a lot of guides, the South Branch is the favorite," he says. "It's more challenging; there's a lot of wave action."

But guide Diane Judge said she was just glad people have stopped perceiving the Chicago River as nothing but a sewer.

"I've lived in Chicago all my life," she says, "and it's all wonderful."

Trip Tips: Paddling the Chicago River

© Beth Gauper

Canoe trips: Friends of the Chicago River offers canoe trips and also public events.

Boat rentals: Chicago River Canoe & Kayak rents boats on the North Branch of the river, two miles west of Wrigley Field at 3400 N. Rockwell, just south of Addison Street, and also in Skokie and Winnetka.

Kayak Chicago rents kayaks for paddling on the North Branch, by the North Avenue Bridge near Goose Island.

Urban Kayaks rents boats on the Riverwalk at Columbus and Wacker and on the lakefront at Monroe Harbor.

Launch cruises: Wendella Boats gives 1½-hour narrated boat tours of the Chicago River and Lake Michigan all day from its dock on the northwest corner of the Michigan Avenue bridge.

Mercury Chicago's Skyline Cruiseline also offers three Chicago River and Lake Michigan cruises, one by night and one that allows dogs, from its dock on the southeast corner of the Michigan Avenue bridge.

Water taxis: The Chicago Water Taxi takes passengers between Michigan Avenue and Chinatown.

Shoreline Sightseeing offers water taxis along the river from the Ogden Slip near Navy Pier to the Willis (Sears) Tower and also on Lake Michigan to the Museum Campus.

Architecture tours: From May through late November, Chicago Architecture Center river cruises are held several times daily from the Michigan Avenue Bridge.

Tickets should be reserved well in advance for summer weekends, either at the CAF centers, river ticket booth, city visitor centers or from TicketMaster, 800-982-2787.

Wendella Boats also gives a daily 75-minute Chicago River Architecture Tour. The dock is at the Michigan Avenue Bridge.

Kayak Chicago gives three-hour architecture/history tours of downtown Chicago from the river on weekends from May through October.

For more, see Skyscraper city.

Planning your trip: If you want a hotel with a Chicago River view, several are clustered around the Michigan Avenue bridge, including the Club Quarters at Wacker, which has great views from its art-deco Mather Tower; its neighbor, Hotel 71.

For more planning information, see Chicago as you like it and our other Chicago stories.