Road trip: Northeast Iowa

In these scenic bluffs, extraordinary people lived and worked.

© Beth Gauper

There's something inspiring about a certain pocket of northeast Iowa.

It's nurtured a a beloved children's-book author, a famous composer and two brilliant woodcarvers. It's stirred battalions of people who create art, preserve heirloom seed and carry on Norwegian culture.

There are a lot of stories in these hills and valleys on the edge of the Driftless Area, which escaped the flattening effects of the glaciers.

In Burr Oak, Laura Ingalls Wilder spent a year far from the prairie. Pa managed a hotel and saloon, Ma emptied chamberpots and 9-year-old Laura sought peace and quiet in the cemetery.

They were so poor the doctor's wife tried to adopt Laura; after the hotel owner's son put a bullet through the door while attacking his wife, the family fled, their debts unpaid.

On the ridges around Decorah, Diane and Kent Whealy began propagating morning glories and tomatoes from seeds her great-grandparents brought from Bavaria in the 1870s.

They founded Seed Savers Exchange to preserve and share heirloom seeds, and now thousands visit the gardens and orchards of its 890-acre Heritage Farm.

Decorah thrived on an influx of Norwegians. They founded Luther College in 1861 and Vesterheim, their "home in the west," in 1877.

It's now the nation's largest museum dedicated to a single immigrant group. Artists and musicians gravitated to the picturesque town and made it a center of culture.

Genius found a foothold in Spillville, where Antonin Dvorak spent the summer of 1893 writing his "American" String Quartet. On a farm, Frank and Joseph Bily spent three decades sculpting musical clocks, one of which Henry Ford tried, and failed, to buy for $1 million.

This is Iowa, but it's not flat, and it's not dull. Little more than two hours from the Twin Cities, it's fertile ground for exploration.

The scenery starts just south of Rochester, where outcrops of golden limestone start to jut from roadsides. The Amish settled here, and when we passed through Canton one fall, we stopped to stock up on the cashew crunch, baked goods and jams that Amish women sell from their buggies.

© Beth Gauper

Burr Oak: bad memories for Laura

Burr Oak is only a few minutes away, just across the state border. In 1876, the stagecoach and wagon crossroads already was starting to fade, but it was a town, and the Ingalls family, including future author Laura, was uncomfortable there.

Laura's beloved Pa already had failed twice, moving from the Big Woods near Pepin to eastern Kansas, where he built a house on land he didn't own, then back to Wisconsin and west to Walnut Grove, Minn., where a grasshopper invasion was in progress.

Then they traveled to Burr Oak, where Pa helped manage the 1856 Masters Hotel; along the way, Laura's infant brother Freddie died.

Today, the hotel is the Laura Ingalls Wilder Park and Museum. It shows several of her possessions — plus a suit worn by her teacher and many items like those she mentioned in her books, including wooden butter molds, twists of slough grass used for heating and a three-footed "spider" kettle.

There's a copy of the test she had to take to become a teacher and a copy of her unpublished autobiography "Pioneer Girl," which does mention Burr Oak.

And there's a photo of Mrs. Eunice Hall Starr, the doctor's wife who tried to adopt Laura and give her a better life.

The books paint a rosy picture of life on the frontier, and it was even rosier in the hit TV series "Little House on the Prairie." So the many people who follow the Laura Ingalls Wilder route around the Midwest often are surprised to see that reality for the Ingallses was much harsher.

"I love all kinds of pioneer stories, but I don't think I would have made a very good pioneer," said Arlene Schoeneck of Shakopee, Minn., who was touring the Master's Hotel with her husband, Don.

After the disastrous year in Burr Oak, often called "the missing link" because Laura never wrote about it in her "Little House" books, the family returned to Walnut Grove, then moved on to De Smet, S.D.

Rural Decorah: heirloom seeds

Not far down U.S. 52, immigrants from Germany and Norway were working farms on the ridges and valleys around Decorah.

A century later, their great-grandchildren realized many of their vegetables and fruits were disappearing, and they began to collect the seeds and share them with other gardeners.

Today, Seed Savers Exchange preserves more than 25,000 endangered varieties at its 890-acre Heritage Farm, where visitors can hike on trails, tour gardens and buy heirloom seeds and garden gifts at the visitors center.

© Beth Gauper

The center's displays and the racks of colorful seed packets are eye candy for adventurous gardeners like Mary Lewman-Stork of Carroll, Iowa, who picks something new every year.

That year, she grew fat snake gourds that grew off the trellis, hit the ground and started growing back up; next year, she plans to grow prehistoric-looking dinosaur gourds and bulé gourds that look like giant wart-covered apples.

"I grow them just to amaze my friends," she said. "I like to keep them guessing about what I'm going to grow next."

Megan Rutter of rural Canton has an heirloom apple and pear orchard and was at Seed Savers looking for melon seeds. She's a frequent visitor, she said.

"It's addictive, seeds are addictive," she said. "The pictures are bad — I see them and say, 'Oh, I want to grow that.'"

It was easy to catch the bug. On the spot, we decided to plant an ornamental vegetable garden, so Rutter helped us pick out purple basil, purple-and-white striped beans, golden beets, sweet marjoram with white flowers and a pink-and-orange Swiss chard called Five-Color Silverbeet.

© Beth Gauper

Decorah : Norwegian heritage

Norwegians settled Decorah, and their cultural center is Westerheim, or "home in the west."

The museum on Water Street was founded even as Norwegian immigration to America was peaking. It now occupies nearly a square block and includes a stone mill, a church, a school, a blacksmith shop and several houses, including one brought from Norway.

People come from all over to see the exhibits, listen to lectures and take classes from renowned artists who have elevated rural folk crafts to high art.

There were intricately painted ale cups and porridge boxes, chip-carved plates, knifes with tooled-leather sheaths, a triangular birch hat box with burnt decor and ironwork latches — practical items, but all so lovely.

"I think in cold, dark Norway, to make every day beautiful, that was something special," said Joan Leuenberger of Vesterheim.

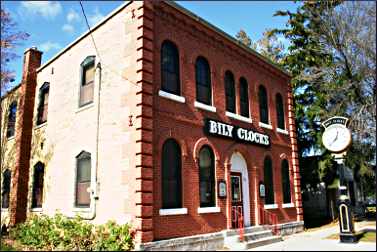

Spillville: Dvorak and two inspired woodcarvers

Only 15 minutes from Decorah, two self-taught bachelor farmers were creating beauty of their own. They spent long winters carving fantastic clocks — more accurately, huge wooden scenes packed with moving figures, with a time-keeping mechanism attached.

At first, they carved lacy Gothic-style clocks reminiscent of European cathedrals; their 1915-16 Apostles Clock featured the 12 apostles parading over a panel of Prague, where their parents were born.

But within a decade, Frank and Joseph Bily had forged a distinct American style, often using the warm gold butternut wood found on their farm.

© Beth Gauper

Their American Pioneer History Clock plays "America the Beautiful" and features 57 historical figures; they were asked to take it to the 1933 Chicago World's Fair and refused. Henry Ford offered $1 million for it, and they refused.

They made a Travel Clock, with relief carvings of Viking ships and zeppelins; a Statuary Clock, with such heroes as Kant, Michelangelo, Ibsen, Zebulon Pike and Pioneer Women; and the Village Blacksmith Clock, inspired by Longfellow's poem of the same name.

All of the carvings came from pictures they found in books or on postcards, including the Little Brown Church of the Vale in nearby Nashua.

"They never traveled more than 35 miles from home, and the Little Brown Church was 40 miles away," said guide Ray Oblander.

Tourists beat a path to their door, and the brothers showed the clocks for a fee of 10 cents. They never sold any of them, planning to leave them to their unmarried sister for her care after their deaths.

"But she died first, and they were so upset they were going to burn the clocks," said guide Adella Kuhn. "Luckily, their neighbors talked them out of it."

Tours of the Bily Clocks Exhibit are accompanied by the music of Antonin Dvorak, who lived in the brick building in 1893. The upstairs floor is devoted to the Czech composer, who came to New York to head the National Conservatory for two years but missed his homeland.

After listening to his assistant's stories of growing up in Spillville, he decided to take his family there for the summer.

"The teacher and parish priest and everything is Czech, and so I shall be among my own folk," he wrote. "How good it will be."

He got up at 4 each morning and walked along the Turkey River, listening to the birds; the song of the scarlet tanager became part of his "American" string quartet, written in Spillville. He went fishing with local boys, played cards with old-timers and played organ for the 7 a.m. mass at St. Wenceslaus.

He listened avidly to the music of Kickapoo Indians who came to perform a medicine show; that, too, appeared in his quartet. And when Dvorak later wrote his famous "New World" symphony, the little Czech village in Iowa became part of music history.

This rolling landscape has inspired a remarkable array of people over the years. Today, tourists are reaping the rewards.

Trip Tips: Northeast Iowa

When to go: Hours at many businesses and attractions are reduced after Christmas; call in advance.

Laura Ingalls Wilder Park & Museum in Burr Oak: It's open daily from May through October, then Thursdays-Saturdays to mid-October. Hours are subject to change; call before visiting. 563-735-5916.

Seed Savers Heritage Farm: It's six miles north of Decorah, on North Winn Road off U.S. 52. It's open to visitors daily from March through October. 563-382-5990.

Vesterheim Norwegian-American Museum in Decorah: It's open daily. 563-382-9681.

Bily Clocks/Dvorak Exhibit in Spillville: It's open daily from May through October, and other times by appointment. 563-562-3569.

Lodging and dining: Decorah has many places to stay and fine places to eat. For more, see A pocket of Norway.

Nightlife: There's always something going on around town or at Luther College, often at its Center for the Arts.

Information: Decorah tourism, 800-463-4692.