Playground in the woods

At Deep Portage in northern Minnesota, adults take a tip from the kids.

© Beth Gauper

As adults, we sometimes forget how great it is to be a kid.

People give you toys to play with. They show you new games and explain things in interesting ways. They feed you freshly baked cookies and s'mores.

Kids take it for granted. But I didn't one January, when I got to stay at Deep Portage Learning Center, in the woods north of Brainerd.

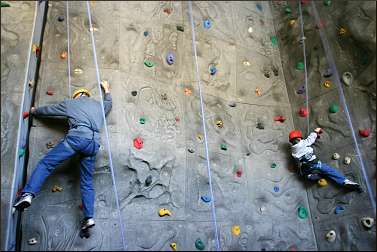

Deep Portage is the largest of Minnesota's environmental-learning centers, with seven lakes and nearly 10 square miles of forest set on rolling glacial moraine. There's a handsome cedar and fieldstone lodge with an indoor climbing wall.

There's an orienteering course in the woods, plus snowshoeing and 11 miles of groomed trails for skiing.

There's ice fishing, broomball and curling on the lakes.

Basically, Deep Portage is a big playground, and it's open to everyone.

Schoolchildren from around the state get to use it during the week, when they stay for several days at a time. They play voyageur games, build quinzees in the snow and learn how to track animals and use a compass.

On weekends, the center is open to adults, who can do exactly the same things. But they also can relax by the fire with a thriller, have a glass of wine, stay up late playing board games or go out to watch the stars.

Kid-style fun with grown-up freedom: It's the perfect combo.

"It's just wonderful to come up and do as much as you want to," says Linda Paige of Grand Rapids, Minn., who came to play and ski during a winter weekend with 20 members of her kayaking club, the Paddle Pushers.

Deep Portage can't afford to advertise much, but in 2004, director Dale Yerger bought a Ginzu groomer and started promoting Deep Portage as "Minnesota's best-kept secret in Nordic ski destinations."

"We've been working for a couple of years to get the word out," he said. "Of course, if we get two or three feet of snow, it could get people thinking."

© Beth Gauper

There was an inch of fresh snow when we were there, and some guests did ski on Big Deep Lake. But there was so much else offered that many of us decided to tag along with the six young naturalists, like the big kids we were.

The first evening, after a dinner of homemade chili and corn chowder, we went on a night hike with Katie Colvin and Bekah Holman, and on Bass Pond, Colvin had us pretend we were pirates, covering one eye with our hands while looking into her flashlight.

When we uncovered our eye, the night suddenly seemed much brighter.

"What were the pirates looking for?" Colvin asked. "Treasure. And where was it? Down in the hold, where it's dark. Pirates wore patches so they could go into the dark and find the treasure."

On the trail, she handed out crayons and told us to write our names and the color of the crayon. Only one person got the color right.

"It has to do with the rods and cones in our eyes," Colvin said. "The cones are for color, and they're not doing a very good job because they need a lot of light. The rods are working overtime because there's not very much light."

The next morning, after a breakfast of eggs, potatoes and lemon-poppyseed cake, we went out to play games — pretending we were Indian boys hunting rabbits with heavy sticks, except we tossed our sticks at coffee cans; trying to throw tomahawks into a stump, a skill needed by hunters and sawyers; and flinging spears with the help of an atlatl, an Aztec word for spear-thrower.

Then we followed naturalist Casey Stanley to the observation tower — "55 feet of fun," he said — for a wind-whipped view of the terrain, where glaciers pushed rubble into hills and dumped chunks of ice that became ponds.

The next activities were ice-fishing and climbing.

On the climbing wall, six rope lines dangled over three stories of brightly colored and oddly shaped knobs that, to my surprise, were not always easy to grasp.

On my second climb, naturalist Stanley helped by calling out Twister-style instructions: "Left foot on yellow," and "look for the white coconut."

We didn't exactly scale the wall like monkeys, but we did it. Shelly Greenwood of Andover, Minn., was as worn-out but exhilarated as I was: "I hadn't done that before, but I think I'd like to do more," she said.

© Beth Gauper

Meanwhile, the ice-fishing group had seen a lot of ice, but no fish.

"I'm glad I had the experience, but I don't think I need to do it again," said Karen Gromala of St. Paul.

We got our competitive juices flowing on the orienteering course, where naturalist Becca Zaffke sent four teams tearing through the woods with compasses, two-way radios, a topo map and a sheet listing the number of paces and compass setting required to find six numbered poles.

My team found the first four poles, usually 30 paces and to the right of where we thought they'd be, but we came up blank on the fifth, and so did another team.

We crashed around in the brush for a while, but it was getting dark, so we gave up and called for directions back to the lodge. When we asked where the darn thing was, naturalist Laura Nordaas was sympathetic.

"It's on a rise, but everything's on a rise," she said. "Don't feel bad; it's one of the toughest ones to find."

For dinner, the Deep Portage cooks had prepared pork tenderloin, mashed potatoes and gravy, green beans and chocolate cake. Afterward, Nordaas went out to build a bonfire and offered s'mores, but nobody budged.

We were finished with the outdoors that day; the kayakers were hunkered down in front of the dining-hall fire, and many of the rest of us were playing Taboo and Yahtzee.

By morning, the temperature had plunged to 15 below, but we still went on an animal-signs hike through the bog with educator Tyler Behrends.

Winter is the only time anyone can go through it, he said, as we walked over spongy beds of bog grass and followed narrow channels where stagnant water would collect in spring.

Beavers had built lodges in the bog, and we checked three lodges until we found someone at home — we knew because we could see puffs of beaver breath coming out of a vent. It was one of the coolest animal signs we'd ever seen.

On the way back, we found not only deer beds among the pine needles but the deer themselves, and Behrends saw a snowshoe hare hopping away.

© Beth Gauper

But we still were thinking about beavers, and at the lodge, we gathered in the theater and Behrends showed us amazing underwater footage of beavers from the BBC series "The Life of Mammals."

At Deep Portage, everyone's a friend of animals, but that goes hand-in-hand with hunting. The center was founded in 1973 on tax-forfeited county land, with help from the Izaak Walton League, and in summer the staff teaches hunting and fishing to youths as well as adults.

"Sometimes, when we say 'environmental learning center,' it conjures up preservation, tree-hugging and scratching Bambi between the ears," said director Yerger. "So then people are shocked that we teach kids how to shoot deer — and clean and butcher them, too."

The Deep Portage schedule includes programs on rifle-sighting, bird-banding and gun-dog training. And people from the community or nearby resorts often come by to join naturalist hikes or have wild mushrooms identified.

"We try to have a great diversity," Yerger says. "The common thread is environmental literacy, outdoor skills and education."

The campus makes its guests so comfortable that people who stay there sometimes forget it's a school, not a resort.

"People ask me about Jacuzzis and hot tubs, and I always say, 'Hmm, that sounds a little resorty,' " Yerger said. "We're really more of a ski camp."

Trip Tips: Deep Portage Learning Center near Hackensack, Minn.

Getting there: It's about 3½ hours from the Twin Cities, an hour north of Brainerd.

Accommodations: Guests stay in 27 dorm-style rooms, some disabled-accessible, that sleep six to 10 and each have a full bathroom. Bedding, pillows and towels are not provided.

The rate for a two-night, three-day weekend includes six buffet-style meals. Refrigerators are available for guests' use. The lodge will open for a non-scheduled weekend if it's reserved by a group of 20 or more.

Nature programs: They're held throughout the year and are open to the public, $5.

Information: Deep Portage, 888-280-9908.

For information on other ELCs, see Minnesota's environmental learning centers.