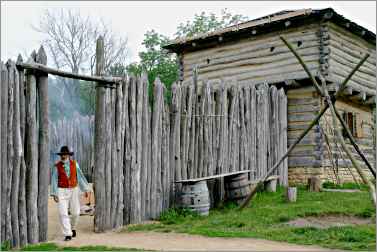

Black Hawk on the Apple River

Near Galena, a fort interprets a Sauk leader who has gripped imaginations since 1832.

© Beth Gauper

Just 15 minutes from the tourist playground of Galena, a young woman scrubs a cast-iron pot with a corncob.

Another woman sews the ticking for a straw mattress. Over an open fire, a man carefully pours molten lead into a mold, which he opens to reveal a shiny new musket ball.

Today, the village of Elizabeth, Ill., sits on U.S. 20, the well-trod path that brings hordes of Chicagoans to this picturesque corner of Illinois, across the Mississippi River from Dubuque.

But in 1832, it was an isolated lead-mining settlement whose residents had followed the Apple River up from the Mississippi.

In April, they heard that the legendary Sauk leader Black Hawk and 1,200 followers had returned to their homeland at present-day Rock Island, Ill.

In May, they heard that Black Hawk had headed north and killed a dozen militiamen near present-day Rockford, Ill.

In a panic, the settlers threw a log palisade around two cabins, creating a small fort.

In June, a militia captain named Abraham Lincoln and his men camped there overnight. And on June 24, Black Hawk and about 150 warriors attacked it.

Only a few men were inside to defend it. But a woman named Elizabeth Armstrong rallied the women, who steadily reloaded muskets as soon as the men fired. In less than an hour, Black Hawk decided he was outgunned and left to plunder nearby houses.

Fifteen years later, the fort was torn down and used as barn lumber. But in 1995, its site was rediscovered, and the fort was rebuilt as the Apple River Fort State Historic Site.

It was the only fort Black Hawk attacked during the four-month "war," which enhanced the fortunes of many politicians, including President Andrew Jackson, who was up for re-election.

Of course, the government won. But in time, the war was recognized as a shameful debacle, and the little fort in Elizabeth tells the story.

"Everybody loves a good drama, and this is a great one," says site manager Susan Gordy. "Black Hawk is the greatest underdog ever. But sadly, within our history, underdogs don't get that sympathy unless really bad things happen to them."

False promises

The Sauk and Mesquakie, or Fox, had flourished in southern Wisconsin and western Illinois, cultivating fields of corn and hunting.

© Beth Gauper

But in 1804, four Sauk men, who had traveled to St. Louis on another matter, were persuaded to sign a treaty that ceded 51 million acres of land to the U.S. government for $2,234 plus $1,000 per year in goods and the use of their land until the government sold it to settlers.

The men were not chiefs, and tribal councils had not authorized a sale. By 1829, when the U.S. land office sold the land around the main Sauk village of Saukenuk, where Rock Island now stands, most of the treaty signers had died.

Its terms and boundaries were unclear to the Sauk, and debts to traders had swallowed the small annuities paid to the them.

"What right had these people to our village and our fields which the Great Spirit had given us to live upon?" Black Hawk said. "My reason teaches me that land cannot be sold."

He and his band returned to plant corn in 1830, but when they came in 1831, militiamen were called to drive them away.

In 1832, on the strength of promises of help from other tribes and the British, with whom he had fought in the War of 1812, Black Hawk again returned.

But by the time he found the promises were false, a military force of soldiers and volunteers had mobilized against him.

Black Hawk fled north and tried to surrender near Rockford, but overexcited militiamen fired on his unarmed scouts.

When Black Hawk appeared, they panicked and ran; the subsequent deaths of a dozen white men sparked war fever, with belligerent politicians and newspaper editors demanding revenge.

Another surrender attempt was thwarted by lack of an interpreter. Undisciplined volunteers (Lincoln left earlier and later ridiculed other soldiers' claims to fame) killed, among others, an old blind Sauk and a grieving warrior sitting on the grave of his wife.

By the time the band finally reached the Mississippi, south of La Crosse, Wis., only 500 members remained. Before they could cross, the armed steamboat Warrior appeared.

When the Sauks approached it to surrender, they were greeted by cannon fire.

It became known as the Bad Axe Massacre. At its end, only 150 remained of the original band of at least 1,200 people.

"It was a horrid sight to witness little children wounded and suffering," wrote witness John A. Wakefield. "It was enough to make the heart of the most hardened being on Earth ache."

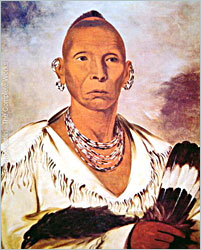

Mighty warrior

Apple River Fort tells both sides of the story. One May weekend, costumed interpreters were going about their chores, and visitors were welcome to ask about frontier life and the war.

"I don't think I'd want Black Hawk attacking me," said volunteer Robert Lopp, who was making musket balls from locally mined galena ore. "There were 200 of them up there in what used to be the garden, yelling and screaming."

© Beth Gauper

"It was a scary time," said interpreter Janice Myelle. "The folks were afraid. They knew Black Hawk; they knew he was a mighty warrior."

The settlement later was named for Elizabeth Armstrong, who led the defense — at least, that's the official story.

"There were three Elizabeths at the fort, so it depends on who you're descended from," Myelle says.

Gordy finds it interesting that women figured so prominently in the conflict. The Sauk women were the cultivators, and they were unhappy with the hard, unbroken sod in Iowa.

"The Native American women said to Black Hawk, 'We will follow you, if we can grow corn in our own fields,' " Gordy said. "And here at the fort, you have that girlpower, 'We're going to fire those guns.' "

In the visitors center, a film re-enacts the events at Apple River and continues the story. At the Mississippi, Black Hawk urged his band to follow him north rather than try to cross.

After the massacre, he was caught by the Ho-Chunk and turned over to Col. Zachary Taylor, who later became president of the United States, and a guard named Jefferson Davis, who became president of the Confederacy.

Black Hawk was taken to the East, where his appearances drew so many people, Gordy says, Andrew Jackson canceled campaign stops that coincided with his.

"People had been told he was the scourge of the prairie, and then they bring in this 65-year-old man in white man's clothes who doesn't look very scary," she says. "That's when you start getting this sentiment that he's this noble savage."

After the war, hotels, bridges, railroad lines and even towns and counties were named for the Sauk leader. So were typewriter ribbons, rye whisky, soda and cigars.

"A lot of military commanders had respect for him," Gordy said. "He had only 500 warriors, and it took 16 weeks for the entire U.S. Army to find him."

The Tyranena Brewing Co. in Lake Mills, Wis., makes a beer named for him: "We celebrate this Sauk leader and his courage with our BlackHawk Porter, the kind of beer that make you say, Ma-ka-tai-she-kia-kiak (Black Sparrow Hawk)!"

In Prairie du Chien, Wis., a bronze sculpture of Black Hawk was the first piece installed in the Mississippi River Sculpture Park on St. Feriole Island.

At least four books about the Sauk leader were published around the anniversary, including "Black Hawk: The Battle for the Heart of America" by Kerry Trask, who spoke during the fort's commemoration.

Black Hawk was a brilliant military strategist and a family man, devoted to his people and to his wife, who survived him. Despite the culture gap, many white people found it easy to relate to him.

"Rock River was a beautiful country," he said. "I loved my towns, my cornfields, and the home of my people. I fought for it."

Trip Tips: Apple River Fort in northwest Illinois

Getting there: Elizabeth is just 15 minutes east of Galena on U.S. 20.

Hours: Apple River Fort is open Wednesday-Sunday from May through October and Thursday-Saturday from November through April. It's free, but donations are welcome.

Black Hawk sites in Wisconsin: The last part of Black Hawk's flight through Wisconsin is marked by explanatory plaques.

The Vernon County towns of Retreat and Victory are named for the conflict.

The trail ends in Blackhawk Park on the river flats north of De Soto, site of the Bad Axe Massacre. There, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers maintains campsites, a pavilion and playground.

For a Black Hawk Trail brochure, call Viroqua Partners at 608-637-2575.

For more, see Road trip: Black Hawk's trail.