Road trip: Black Hawk's trail

A sorry episode in U.S. history is recounted along the scenic byways of southwest Wisconsin.

© Beth Gauper

In 1804, the clock began to tick for the Sauk and Fox tribes of southern Wisconsin and western Illinois.

That year, their chiefs signed a treaty ceding their lands in exchange for $1,000 per year in goods and the use of the land until the government sold it to settlers.

Tribal councils had not authorized the sale, and the chiefs soon regretted it, but they kept the bargain.

But over the years, most of the signers died. Terms and boundaries became unclear to current chiefs. Debts to traders swallowed the small annuities paid to the tribe, even as settlers and rival Sioux began to squeeze Sauk hunting grounds.

Then, in 1829, the U.S. land office sold the land around the main Sauk village of Saukenuk, where the Illinois town of Rock Island now stands.

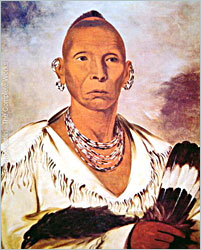

One aging Sauk chief refused to leave the lands of his ancestors. Black Hawk was a brilliant warrior but a gullible and unsophisticated leader.

Still, he was a magnet for the disaffected — whom, three years later, he would lead into a "war" whose romance enhanced the political fortunes of future presidents and governors but eventually was recognized for the tawdry debacle it was.

Remembering Black Hawk

In the 1880s, a young country doctor in southwest Wisconsin began studying the Black Hawk War, talking to witnesses, identifying skirmish sites and cataloging artifacts strewn around the bucolic landscape in which he lived.

For here, 28 years of tension and misunderstanding reached a nadir.

In 1832, on the strength of promises of help from other tribes and the British, Black Hawk had led more than 1,000 followers back to their homelands.

By the time he found out the promises were false, a military force of soldiers and volunteers, including a young private named Abraham Lincoln, had mobilized.

Belligerent politicians and newspaper editors called for scalps. Black Hawk fled north and tried to surrender, but overexcited volunteers attacked his scouts.

Another surrender attempt was thwarted by lack of an interpreter. Undisciplined volunteers (Lincoln left earlier, and later ridiculed other enlistees' claims to fame) killed, among others, an old blind Sauk and a grieving warrior sitting on the grave of his wife.

© Beth Gauper

By the time Black Hawk's band entered Wisconsin, it was starving; by the time it reached the high ridges and coulees of Vernon County, its path was marked by corpses and discarded possessions.

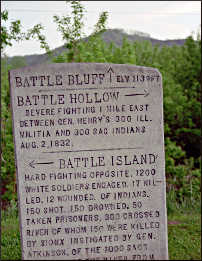

This is where Dr. C.V. Porter picked up the trail. Unlike many of his era, he was sympathetic to the Indians, and in 1930 he made a series of roadside markers, recording the story of each site by pushing newspaper headline type into fine concrete.

"He didn't want the people to forget what did happen," says Vernon County historian Judy Gates. "It's a very important event in county history, and in U.S. history."

But over the years, Porter's markers slid into ditches and became surrounded by corn fields.

Eventually, the Vernon County Historical Society restored them and erected shelters and explanatory plaques. For the dedication, descendants of Black Hawk traveled from Oklahoma, where the tribe ended up.

Today, it's possible, with the help of a society brochure, to follow Black Hawk's flight to the Mississippi.

Pilgrimage to Wisconsin

A friend and I started out one sunny September afternoon near the tiny burg of Rising Sun, where the band camped in a ravine July 31, 1832, followed by the militia the next night.

Today, contoured fields of soybeans and tobacco line the valleys, and ridges are dotted with white steeples and farmhouses.

Scandinavian pioneers homesteaded here; near Coon Valley, the 400-acre open-air museum Norskedalen keeps their traditions alive.

Pockets of Germans settled to the north, and Italians along the river, in the towns of Genoa and De Soto.

Freed slaves came to farm in the east part of the county before the Civil War; the son of one former Tennessee slave designed many of the round barns for which the county is renowned. The Amish now live in the scenic Kickapoo Valley, around Ontario, Cashton and LaFarge.

This hilly terrain helped Black Hawk throw off the militia, in an effort to buy time to build rafts and escape across the Mississippi.

He sent 20 decoys, most of whom, according to Marker 5, were shot when they tried to surrender. It presaged the slaughter to come.

© Beth Gauper

Massacre on the Mississippi

On Aug. 1, the remainder of Black Hawk's band arrived at the Mississippi. Suddenly, the armed steamboat Warrior appeared.

Under a white flag of truce, the Sauks approached it to surrender and were greeted by a hail of lead. Black Hawk and a few followers headed north, but the rest of the band elected to try to cross the river.

The next day was the real bloodbath: Routed from wooded islands by the Warrior's cannons, most of the band, including women and children, were shot or drowned.

Sioux sent by the whites caught up with those who had escaped and brought back 68 scalps; Menominee and Winnebagos hunted others.

The "battle" site now is part of Black Hawk Recreation Area, which includes campsites, a pavilion and playground on the river flats north of De Soto.

A plaque there quotes Black Hawk, who later was caught by Winnebagos and turned over to Col. Zachary Taylor and a guard named Jefferson Davis.

"Rock River was a beautiful country," he said. "I loved my towns, my cornfields, and the home of my people. I fought for it."

Trip Tips: Black Hawk's Trail in southwest Wisconsin

Getting there: The Wisconsin sites are half an hour south and southeast of La Crosse.

Maps: The Vernon County Historical Society in Viroqua has self-guided driving tour maps of the Black Hawk markers.

Information: For more about the area, see Valleys of Vernon County.

Illinois sites: Near Galena, Black Hawk's band besieged the town of Elizabeth. The town palisade has been re-recreated as the Apple River Fort State Historic Site.

For more, see Black Hawk on the Apple River.

In Oregon, Ill., a 48-foot statue known as Black Hawk overlooks the Rock River.

For more, see On the Rock River in Illinois.