Place of the Long Rapids

Across the Rainy River, the long-dead mean much to modern-day Ojibwe.

© Torsten Muller

Along an international border, it's surprising how much difference a few yards can make.

To many Minnesotans, the stretch of Rainy River between Baudette and International Falls is beyond boondocks. It's beautiful — the highway that hugs it is the most scenic part of the 191-mile Waters of the Dancing Sky Scenic Byway — but it's far off the beaten path.

The Minnesota Historical Society closed its Grand Mound Historic Site there, and Franz Jevne State Park is visited so infrequently the Minnesota DNR doesn't staff it.

But for Canadians, this is well-traversed land. Their nation's fortunes grew with the traders who traveled this river, and their towns are clustered along the border.

The Rainy River was especially significant to the people who lived there long before the Europeans came. From all across the continent, indigenous people converged on a shallow stretch of rapids where sturgeon spawned, setting up camps and villages a stone's throw from Franz Jevne State Park.

Here they traded, socialized, feasted, connected with relatives — and buried their dead.

The Ontario side of the Long Sault, or Place of the Long Rapids, contains the largest concentration of burial mounds and ancient village sites in Canada and is a national historic site.

Today, the Ojibwe of the neighboring Rainy River First Nation are guardians of the site, and their impressive Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Historical Centre serves as a link between past and present.

Sacred grounds

One August, I made the trip to Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung, halfway between International Falls and Baudette on the Ontario side of the river.

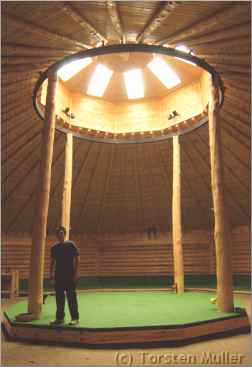

Inside the center, sturgeon swim in an aquarium, and there's a birchbark waaginogaan, or domed lodge. Exhibits explain Ojibwe history and culture in English and Ojibwe.

On the walls, large photos from the 1920s and '30s show people harvesting wild rice and playing moccasin games, and cases show artful cradleboards and bandolier bags.

In a pleasant restaurant, venison stew, walleye, wild-rice soup and fry bread are served, along with fried chicken and such specials as pierogi, the filled dumplings favored by the Ukrainians who settled in nearby Fort Frances. There's a gift shop, too.

The center exists, however, because of the burial mounds that line the edges of river terraces. The oldest were built 2,200 years ago, and the latest perhaps 400 years ago; there are at least 24 mounds, one of which was bulldozed before the site was protected in 1970.

The mounds started as a shallow pit, said Graham Hunter, and the deceased were put in and covered with earth so more could be added, perhaps over hundreds of years. The bundled remains were brought in from afar, he said, and often buried with possessions.

© Torsten Muller

"When a person passed, he'd be put in a tree so the body could decompose, and then they'd wrap the bones in birchbark or deer hide," Hunter said. "There could be 1,000 people in a big mound, and they would come from all through North America; there are shells from the Gulf of Mexico."

Hunter, whose father is from the local nation and mother from Minnesota's White Earth community, was our guide as we got into wagons to see the site.

Our first stop was the Round House, where we sat on benches as Hunter explained why the building had nine sides — to represent the nine animal clans of the local Manitou Rapids nation, such as his own Caribou Clan — and why there's a sand "moat"' around the raised stage, with wood figures of a turtle and an eagle.

"When you're dancing in the sacred circle, you can be in direct contact with Mother Earth," he said. "And you can leave tobacco offerings in the turtle, which carries the world on its back, or eagle, because he flies highest and gets closest to the Creator."

Dancers always move clockwise into the future, he said, like the sun and moon.

"There's only one place you'll walk counterclockwise, and that's around someone's grave," he said. "That's the only good time to look back and to reflect on things."

Ojibwe burials are celebrations, he said, with feasting and card playing: "a good time, not a sad time."

Farther down the river, at one of the mounds, Hunter gave us our own chance to pay respects to the dead, some of whom had to be retrieved from a government archaeologist and reburied.

With our left hands, the ones closest to our hearts, we received pinches of tobacco to place on the mound; walking around it counterclockwise, we used our right hands to add benedictory handfuls of dirt.

At the oldest and tallest mound, we admired the view of the Long Sault, lined by mixed forest and the oak savanna prairie to which the site is being restored.

"The first time here, I had such an overwhelming sense of peace," said Rita Moorhouse of Fort Frances, who had come with her two sons and a friend visiting from the Toronto area. "I think it's a marvelous place. Just to come here and walk the trails on a beautiful day, you get a real sense of the sacred grounds here."

Bucking stereotypes

Like many nonprofit cultural centers, however, Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung (emphasis is on the second syllable) is on thin ice financially, though it gets some support from the provincial and national governments.

"There are a lot of people around here who have never heard of us," Hunter says. Still, he says, some think they know something about aboriginal people.

"There are still a lot of negative stereotypes," he said. "We're all on welfare, everybody drinks alcohol — I run into people (who think) like that everywhere."

And some who do visit Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung are just as unrealistic, expecting to see "leather and feathers."

"We had a group of Germans come, and they were mad when they got here and we actually had clothes and telephones," Hunter said.

On the U.S. side of the river, there's nothing to mark the vibrant culture that once existed along the river or the first-rate cultural center that's there now.

At Franz Jevne, a plaque marks the Long Sault but does not mention the mounds just a few yards away. Down the road, Grand Mound interpretive center is unmarked; people who know it's there and venture beyond the barriers are greeted by swarms of mosquitoes.

Koochiching County and the historical society would like to bring back Grand Mound, which is just 17 miles west of International Falls.

It's the largest concentration of burial mounds in the Upper Midwest and reflects a society nearly as sophisticated as the one that left Cahokia Mounds in Illinois, said Ed Oerichbauer of the Koochiching County Historical Society.

For one thing, he says, International Falls needs more to attract tourists.

"To network with Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung would be the perfect thing to encourage people to cross the border; there's something to do on both sides," he says.

And for another, people have a right to know their history.

"The average Minnesotan, depending on where they are, thinks there aren't any Indians anymore, or if there are, they're operating casinos," Oerichbauer says. Schoolchildren from all over northern Minnesota came to see Grand Mound when it was open, he says.

"It was a big deal," he says. "Now, it's sitting rotting in the ground with nothing going on; it doesn't make sense."

The Rainy River burial mounds on both sides of the river, Graham Hunter says, give people today an unparalleled chance to connect not only with the past but also with each other.

"If we educate people on our history, our culture, it brings us closer together," he says. "If we do that, we can bridge the gap."

Trip Tips: Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Historical Centre

Getting there: It's about 5½ hours to International Falls and Fort Frances from the Twin Cities; from there, the center is about 40 minutes west on Ontario 11, between Barwick and Stratton. It also can be reached from Baudette; from there, it's a half-hour east.

Call in advance. The cash-strapped center operates under a constant threat of closing.

Crossing the border: You'll need a passport or passport card. At International Falls, there's a fee to use the private bridge through the paper plant (it's free on the way back).

Tours: They're given throughout the day. The center is open Wednesday to Sunday from May through October.

Events: Father's Day weekend, Rainy River First Nations Powwow.

Dining: Hungry Hall is a good place to eat, serving such dishes as cream of wild rice soup, wild blueberry pancakes, walleye, venison stew, fried chicken and bannock.

Franz Jevne State Park: The quiet park on the U.S. side of the Long Sault has campsites and picnic areas along the Rainy River.

Accommodations: With advance notice, Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung will put up canvas tepees. Guests can use the shower and kitchen at the Round House.

Information: Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung, 888-992-9949.

For information on accommodations and dining in International Falls, see Land of big water.