H.H. Bennett's Wisconsin Dells

Thanks to a 19th-century photographer, tourists flooded in to see the famous rock formations for themselves.

© Beth Gauper

H.H. Bennett wanted tourists to come to the Wisconsin Dells, and thanks to him, they came.

Boy, did they come.

In Bennett's day, they stayed for weeks, playing croquet and checkers and going on picnics, boat excursions on the Wisconsin River and perhaps to a magic-lantern show of stereoscope slides from Bennett's studio.

Now they stay only a few days, but they come in droves, flocking to thrill rides and theme parks, magic shows and musical revues. The Dells today are a first-rate tourist trap — and the pioneering photographer might have been fine with that.

"He has given to the Dells a notoriety which it could have gained in no other way," the Wisconsin Mirror said of Bennett in 1884.

Young Henry Hamilton Bennett wanted to be a carpenter, but his right hand was crippled during the Civil War when his gun accidentally discharged.

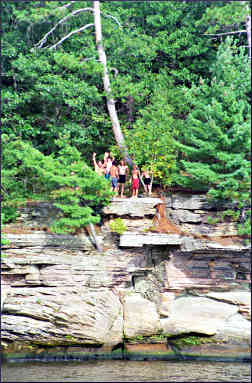

He became a photographer instead, supporting his family through his portrait studio but also by selling photographs of the sandstone formations and shadowy gulches of the Dells, a 15-mile gorge created by a sudden flood at the end of the Ice Age.

He was a tireless promoter and businessman, taking photos as steamboats arrived, rushing to his studio to develop the glass negatives and returning to hawk prints to passengers.

He named landmarks to make them more appealing to tourists — Witches Gulch, Romance Cliff — and sometimes whitewashed the interiors of caves so they'd show up better on his negatives.

To increase revenue, he invented devices that allowed him to produce 75,000 stereoscope cards a month.

H.H. Bennett was a working man, yes — but he also was a brilliant artist and innovator.

© Beth Gauper

"I have digital and everything, and I can't take a picture the way he did 100 years ago," said Annie Kurtz, a Dells native. "And he had a bad right hand."

Even more important, he loved his subject. Other pioneering photographers became famous by portraying the majestic mountain ranges of the West.

But Bennett stayed in Wisconsin, shooting fishermen, logging-camp cooks and picnickers: "I had many opportunities to photograph the West, but I never traveled to record other terrain," he said.

"My energies for near a lifetime have been used almost entirely to win such prominence as I could in outdoor photography, and in this effort I could not help falling in love with the Dells," he said the year before his death.

Bennett's family continued to operate his studio after he died in 1908, and when it closed in 1998, it was considered the oldest continuously operating darkroom in the nation.

Today, thanks to donations from Bennett granddaughter Jean Dyer Reese and her husband, Oliver, it's part of the H.H. Bennett Studio and History Center, operated by the Wisconsin Historical Society.

The museum is a good first stop for tourists, some of whom have no idea that there are dells in Wisconsin Dells, which was called Kilbourn City until 1931, when tourism-minded civic leaders renamed the village.

"When people come to the Dells, you would think it would be the first thing they want to see, but that's not why they come," Kurtz says. "When they come downtown, it's for the T-shirts and ice cream."

The beautifully designed little museum is Wisconsin's own loving portrait of the old Dells and the man who made the tourists come running.

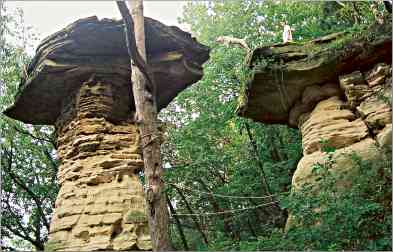

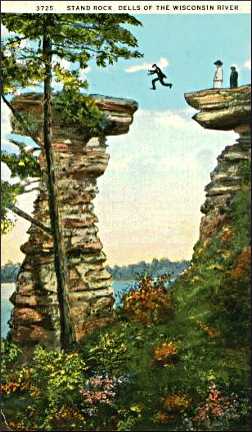

There's a cutout of Bennett's famous 1888 photo of his 17-year-old son, Ashley, jumping the 5½-foot chasm to the top of Standing Rock. The first example of stop-action photography, it made audiences at his magic-lantern shows gasp.

To get the photo, Bennett invented a rubber band-operated shutter he called "the Snapper," and Ashley had to make the jump 18 times before his father captured the image he wanted.

The museum has marked off the distance on carpet for visitors who want to try it, and it's not that easy. Today, dogs make the jump there and back for passengers on Upper Dells boat tours.

He also made many portraits of the local Winnebago, whose dance ceremonials, along with boat excursions, were the only tourist attractions in the Dells for many years.

He tried to learn their language, keeping notebooks of phonetic Winnebago words and their English meanings, and recorded their legends.

© Beth Gauper

According to the Winnebago, who in 1994 reclaimed their original name, Ho-Chunk, the Dells were formed by an enormous serpent who slithered toward the sea, cutting a groove for the river bed with its scaly body.

At the Dells, the serpent squeezed through a crack in the rock, they thought, scraping it into the formations seen today.

Racks of stereoscope views show the Dells in vivid 3-D, before the 1909 Kilbourn Dam divided the Upper and Lower Dells and raised the river 17 feet, obliterating sand beaches and altering views of the formations.

Bennett opposed the dam: "With me, every rock that is to be hidden is a sacrilege of what the good God has done in carving them into beautiful shapes."

Because of Bennett and his heirs, however, much of the old Dells have been preserved. Not only do the photos show the old river, but Bennett's daughter Nellie and her husband, George Crandall, acquired and preserved 1,200 acres along the Upper Dells, which the family later donated.

"Had they not done that, it would've been condos all the way to Mauston," Kurtz said. "And they were not wealthy people; they were just very environmentally conscious."

By the end of the 20th century, tourists were starting to bring their own cameras, buying more souvenirs at the Bennett studio than photos.

The studio museum also sells souvenirs; that's usually what catches the eyes of passing tourists and lures them inside the 1875 storefront, wedged between a trading post and an old-time portrait studio.

Once inside, they'll have a chance to see an era preserved only in Bennett's photographs.

They're all that's left of the old Dells, and after all, said John Muir, a contemporary of Bennett's who grew up in the next county, "no human eye will ever describe them."

Trip Tips: H.H. Bennett's Wisconsin Dells

H.H. Bennett Studio: It's open daily from May through October. Admission is $12, $5 for children 5-12. It's open daily from Memorial Day weekend to mid-September, then Thursdays-Sundays through October.

Details: For more, see The quiet side of the Dells.