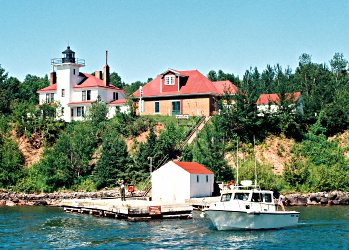

Lighthouses of the Apostles

The allure of a bygone lifestyle pulls visitors to these island beacons.

© Beth Gauper

A century ago, in the Apostle Islands, only seven puny shafts of light stood between sailors and catastrophe.

Lake Superior has been called the most dangerous body of water in the world, an inland teakettle in which any tempest can be deadly.

Storms gather fury over 200 miles of open water, and heaven help mariners caught between wind and rock — heaven or a lighthouse keeper with sharp eyes.

During a ferocious storm in September 1905, Outer Island lighthouse keeper John Irvine saw a lifeboat leave the foundering schooner Pretoria and then capsize offshore. Five men drowned, but the 60-year-old keeper was able to pull the remaining five ashore.

In the same storm, Sand Island keeper Emmanuel Luick had to watch, helpless, as a life raft from the ore freighter Sevona broke up 100 yards from Justice Bay, just south of the lighthouse.

All seven men drowned, and Luick spent the next month rounding up the bodies.

Tales of these early lighthouses and their keepers, who often risked death themselves, still have rapt audiences on Wisconsin's Apostle Islands National Lakeshore.

The 21 islands, off Wisconsin's Bayfield Peninsula, has the greatest concentration of National Park Service lighthouses in the nation.

Visitors arrive in kayaks, sailboats or cruise boats out of Bayfield, eager to see these 19th-century anachronisms. Long after radar and electricity made manned lighthouses obsolete, they still have a grip on modern-day imaginations.

"I like the stories behind them — the rugged way of life, the isolation, the romance of it — though it probably wasn't that romantic," said Kae Lance of Brooklyn Park, Minn., who visited the light stations on Michigan, Sand and Raspberry islands during one of the Lighthouse Celebrations.

© Beth Gauper

Life in a lighthouse, while sometimes dramatic, was hardly romantic. Emmanuel Luick, who served as keeper on Sand Island from 1892 to 1921, married 16-year-old Ella Richardson in 1896.

Though she proved able and eventually was made assistant keeper, young Ella left the island one day in 1905 and never returned.

Anna Marie Carlson was a young bride in the winter of 1893, when her husband, the head keeper, disappeared with his brother after a storm arose as they fished.

Speaking of the ordeal during a 1931 interview, Anna Marie said, "Women who sit in brightly lighted cities with people all around, within call of the voice, have no conception what it is to sit and wait for your man on a deserted island, with snow and ice everywhere and no light but the stars."

For three nights, she worried, left alone with her toddler and two infants. On the fourth day, her husband, Robert, returned, afraid she'd killed herself and the children.

He and his brother had drifted on an ice floe to Madeline Island, where they'd jumped to shore, found an old boat, repaired it and rowed, frostbitten, the eight miles back to Michigan Island.

Robert Carlson's sister, Cecilia McLean, was wife of the Raspberry Island keeper and spent 30 years on isolated Lake Superior islands: "I hate lighthouses," she said later. "If I had my life to live over again, it would not be in light stations."

There are eight lighthouses on six islands, two of them retired.

Park-service rangers give tours of the Raspberry Island light, and the Apostle Islands Cruise Service in Bayfield offers cruises to Raspberry and also Michigan Island, staffed by volunteers in summer.

The lights on Sand Island and Devils Island also are staffed by volunteers, who give tours to tourists who get there in their own boats.

Outer Island is the most remote and exposed to weather. Its 1874 lighthouse tower is attached to a keeper's house, and there's also a fog-signal building.

The two lights on Long Island can't be toured, but visitors can explore the grounds.

Sometimes, the Apostle Islands Cruise Service schedules trips to Sand, Devils and Outer islands as well as Raspberry and Michigan, weather permitting. Tourists are quick to snap up places on the boats.

Michigan Island has two lighthouses, and one September, I hopped a boat over and toured them. Maryland volunteer Bill Hibbard met us, apologizing for the clouds of mosquitoes that swarmed over the island.

© Beth Gauper

The light station, he said, had a curious history: It was first to be built but was abandoned after a year of service, in 1858, when a federal inspector arrived and announced it should have been built on Long Island.

The contractor, consulting local mariners, apparently had decided a light on Michigan made more sense, but its light was extinguished, and he was forced to build on Long.

In 1869, however, the Michigan Island lighthouse was reactivated and used until 1929, when it was retired and a new light placed atop a 112-foot steel tower next door. Today, visitors can climb both structures.

"Feel free to yodel as you go up," Hibbard said as visitors climbed the tower. "It's kind of like a giant organ pipe. I'm a bass, so it's fun; my choir master would never believe it."

Erected between 1856 and 1929, each lighthouse is different.

The 1881 Norman Gothic lighthouse on Sand Island, made of locally quarried brownstone, is reached by a two-mile trail lined by thimbleberries and an antique jalopy rusting in the woods.

The 1862 Raspberry Island lighthouse has a vintage garden.

And because 400 acres around each lighthouse was reserved for the use of the keeper — on Devils and Raspberry, the whole island was reserved — the scenery around each lighthouse includes spectacular stands of old-growth white pine and hemlock.

"Oddly enough, these symbols of civilization ended up actually protecting the largest tracts of unlogged forest in the Upper Midwest," said the park service's Jim Nepstad.

Big or small, old or newer, each lighthouse has its fans.

"Up here, they're all unique," Nepstad said. "They all have a unique personality."

Trip Tips: Lighthouses in Wisconsin's Apostle Islands

Cruises: From Bayfield, Apostle Islands Cruises gives a Grand Tour of the islands daily from mid-May to mid-October and cruises to the Raspberry Island and Michigan Island lighthouses several days a week from late June through Labor Day.

© Beth Gauper

Volunteer keeper positions: The park starts filling the positions on Sand, Devils and Michigan islands in January, ideally for three- or four-week stretches, but positions may be available through spring. There's a lot of work, so couples are preferred.

Keepers on Sand Island stay in a modern cabin but must walk two miles to the lighthouse and have the most campground work. On Devils Island, they have running water but a lot of grass to cut.

Michigan, which has two lighthouses, has the most steps to climb, but the campground isn't busy.

Positions also are available on Oak and Manitou islands. People who are interested should call 715-779-3397, Ext. 303, to discuss opportunities.

Apostle Islands National Lakeshore: The headquarters is in Bayfield at Washington Avenue and Fourth Street.

Accommodations and dining: Bayfield and Madeline Island have many great places to stay and eat.

For more, see Beloved Bayfield and Madeline's magnetism.