High drama at Devil's Lake

Rocks tell the earthshaking story of how the Baraboo Hills were created.

© Torsten Muller

We're at the end of the Ice Age, at the edge of an endless mound of blue ice whose vast, super-cold surface has sent 200-mph winds whipping into Wisconsin.

The winds can strip the flesh off a face in 30 seconds, so the local mammoth hunters have gone south for the winter.

Now the hunters are back, standing at the edge of a milky-white, 70-mile-long lake made by melting ice.

There are 500-pound beavers here, too, and 8-ton bison. The hunters run up to a woolly mammoth, sink an 8-inch spear tip into its neck and dash away.

As they wait for the animal to bleed to death, they hear a rumble, then a roar, as the earth begins to shake. A 100-foot wall of water descends on the valley, cutting through ancient sandstone like a knife through butter.

Suddenly, the landscape has some features we can recognize — the canyons of the Wisconsin Dells, for one.

Ancient history? No, it's high drama, especially when told by Paul Herr, the P.T. Barnum of Wisconsin geology.

"Geologists from all over the world come to see this, and their jaws drop," says Herr, a Madison geologist. "They say, 'I thought I was going to see dairy cows, not one of the most stunning natural attractions on the planet.' "

He levels a stern gaze at his tour guests, gathered under a red pine near the entrance to Devil's Lake State Park.

"I'm glad you found me," he says, "because I'd have to arrest you at the border if you didn't stop to see Devil's Lake."

Devil's Lake, besides being the most-visited state park in Wisconsin, is the centerpiece of the Baraboo Hills, a 25-mile-long swatch of south-central Wisconsin that has been recognized as a "Last Great Place" by the Nature Conservancy.

Its pink quartzite ridges were at the edge of a continent 2 billion years ago, when Wisconsin was covered by volcanoes. Its peaks were tropical islands 500 million years ago.

And 13,000 years ago, it was at the edge of a glacier that dumped piles of 800-ton boulders and, when it melted, created Devil's Lake, one of the clearest lakes in Wisconsin and, many think, the most beautiful.

© Beth Gauper

This glacier stretched from New York state to Puget Sound and deep into Canada. But it was called the Wisconsin Glacier, because it tells its story best in the Baraboo Hills.

"It's just happenstance that so much happens to be in such a small area," Herr says. "Geology doesn't get any better than this."

It takes a real showman to promote geology in a neighborhood that includes the water parks of Wisconsin Dells and the acrobats and clowns of Circus World Museum in Baraboo.

And who could make a kid want a souvenir trilobite fossil as much as a plastic pirate sword? Only Paul Herr, the ringmaster of rocks.

One day, I and six other people piled into Herr's van for a trip back in time. We drove up a gravel-filled ridge that marks the southernmost advance of a 4,000-mile-long glacier.

In the front yard of a stable, we look at a horizon filled by blue glacial ice, and we can hear boulders, carried down from Canada, tumbling off the ice as it scrapes a path northward.

Then we see a giant lake, and we hear a deafening whoosh as an ice dam gives way and sends a wall of water into the valley, creating the Wisconsin Dells in a week.

"Should we say thank you to the glacier before we leave?" Herr asks. "Thanks for making wonderful fishing in the Midwest, and our wonderful lakes in the northwoods. Thanks for making us the breadbasket of the nation; we had very crummy soil, and the glacier spread freshly ground rock and made it very fertile.

"And thanks for making humans; the climatic changes forced people to adapt and promoted development of the large-brained primate."

At the entrance to Devil's Lake State Park, we stopped to look at a towering mound of pink quartzite. It's part of a mile-thick sheet of super-hard quartzite that, 1½ billion years ago, folded up like paper when the edge of another continent collided with it.

© Beth Gauper

Now its edges rise out of the ground around the park, providing the picturesque, 500-foot cliffs around spring-fed Devil's Lake.

Herr uses a laser point to show us the ripples on the rock, formed 2 billion years ago, when it was still sand at the edge of a red ocean filled with iron-eating bacteria.

"We geologists get light-headed when we touch it," Herr said. "It's so ancient, like a relic from the past."

Today, these glassy cliffs are treasured by rock climbers: "They say if you can climb Baraboo quartzite, you can climb anything," Herr said.

We went into the park, past the gorgeous sand beach and one of nine Indian burial mounds. The Winnebago, who could hear echoes bouncing off the cliffs, thought there was an evil spirit in the lake, so European explorers named it Devil's Lake.

Turkey vultures soared above us as we walked to a pile of quartzite boulders, each as heavy as 400 cars, and each looking exactly as it did 13,000 years ago, when they tumbled off the cliff.

© Beth Gauper

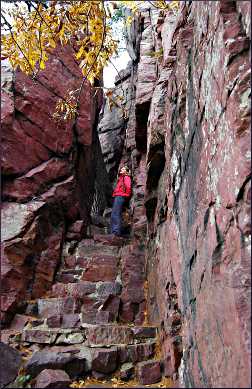

Hiking on the East Bluff Trail, we stopped at the entrance to a narrow cave, and Herr showed us round dings on the quartzite, percussion marks made when the Baraboo Hills were islands and 50-foot waves smacked the boulders against one another.

Then we admired the view of an area Herr calls the Grand Canyon of the Midwest.

Herr says he's happy if only 5 percent of the area's tourists are open to receiving what he calls "the gift of the big picture."

"One of my goals is to stretch the brain a little bit, to get people to see the big picture," he says. "Everyone should know the story of our planet, and life on our planet. And this is one of the best places in the world to learn your own story."

For more on Devil's Lake State Park, see The divine Devil's Lake.

For more about formations in the Dells, see The quiet side of the Dells.

For more about Baraboo, see Baraboo's gilt complex.