On the rocks in the Ozarks

In spring, southeast Missouri is heaven for hikers, paddlers and rockhounds.

© Beth Gauper

Only a day's drive from Minnesota lies a world as old as the glacier-cut north woods are new.

Here, in the foothills of a worn-down mountain range, elephantine boulders stand in herds.

In riverbeds, billion-year-old slabs are as slippery smooth as clay just pressed by a toddler's thumb.

Springs pop out of the Earth's depths, shimmering as blue-green as the Caribbean.

This is what a volcanic landscape looks like after 1.5 billion years of continual erosion: very rocky and very rolling. There's rarely enough topsoil to till, and locals eke out a simple living.

The world of strip malls seems far away — in days of visiting state parks and historic sites, you may never see a single national franchise, just the mom-and-pop cafes and motels of yesteryear.

This is my favorite place to be in spring. By late March, hawthorn and dogwood are starting to bloom, daffodils line rural roads and water runs fast in crystal-clear "float streams," or canoeing rivers.

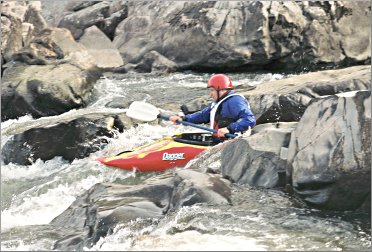

It's a good time to head for southeast Missouri, as I did one March, making it in time for the Missouri Whitewater Championships on the St. Francis River, at Millstream Gardens Conservation Area.

There wasn't really a bank from which to watch, only piles of oddly smooth, gray boulders. I sat on one near the water, as dozens of kayakers and canoeists wove their way through the St. Francis shut-ins.

Shut-ins are what Missourians call a river gorge studded with hundreds of knobs of hard granite and rhyolite, once part of the earth's original crust, then covered by hundreds of feet of sea and sedimentary rock, then exposed again by wind and rain that washed away everything around it.

It took the elements millions of years to wear this landscape down to its bones. By contrast, the terrain of Minnesota and Wisconsin dates only to the retreat of the last glacier, 12,000 years ago.

Everything here is as old as the hills, on which scaly pines, oak and hickory cling to a thin mixture of humus and crumbled rock. In dry, rocky openings in the woods, lizards and prickly-pear cactus flourish.

© Beth Gauper

It's as hospitable as a place can be, however, thanks to laid-back, Southern-style hospitality that always comes with a "ma'am."

When I arrived at the Wilderness Lodge after dark, having negotiated the narrow dirt road from tiny Lesterville, owner-manager Reagan Schall ushered me right to a table in front of one of two wood-burning hearths.

She brought me a glass of cabernet to go with the three-course menu of marinated spinach and broccoli salad, hot bread, grilled flank steak with a curried Bearnaise, glazed carrots, baked potato with a tureen of sour cream, chocolate-cream pie and coffee.

Everyone at the other three tables beamed at me, and I got the feeling we were all very happy to find ourselves at this welcoming little outpost in the Ozarks. The lodge, built by a wealthy sportsman, was a 1927 classic, with chinked log walls, plank floors and kerosene sconces.

After dinner, I drove up the steep hill to my stone cabin overlooking the Black River, changed and drove back down for a soak in the lodge's outdoor hot tub.

I sat, all alone, gazing up at a canopy of stars through the ghostly gray branches of an elm, and when I went back it was with a glass of Riesling that Schall had left for me in the lodge's fridge.

The next day, after a breakfast of eggs, ham, pancakes and biscuits in the sunny "new" dining room, under the mounted heads of bighorn sheep and lynx, I talked with office manager Mariam Smith, who grew up in the area, has worked at the lodge for decades and calls herself "one of the antiques."

"The lifestyle down here is so much different from city life," Smith said. "It seems as if life got so hectic for everyone. Just a few hours down here, and you can tell their business is forgotten."

Outside the office, near a stone building that once was a Catholic chapel, Kathy Pacheco was playing with her teen daughters, Alina and Dana. The St. Louis physician explained her presence at the lodge as "You know — overworked and tired," and laughed.

"You're part of country life down here, a slow pace," she said. "You're not under any pressure to do anything."

My morning's destination was the Dillard Mill, which looked close on the map but actually lay along a roller coaster of country roads.

By the time I reached the lead-mining town of Viburnum — named for the medicinal bark of honeysuckle shrubs by Mariam Smith's great-grandfather, the local doctor — I felt queasy, and was glad to get out and walk the trail to the 1908 mill.

© Beth Gauper

At the turn of the century, there were hundreds of water-powered mills in Missouri's hill country; the Dillard Roller Mills was unusual because it was owned by a woman, Polish immigrant Marie Mischke, who ran it for 10 years before selling it back to her brother, Emil.

It produced Ozark Pride Flour for many years, but closed in 1956 and now is a state historic site.

It was too early in the season for tours, but my timing won me the perfect Ozarks souvenir: a completely intact opossum skull, which I spotted lying at the base of a tree.

I pocketed it and walked on to the barn-red mill, perched over a rock dam at the junction of two creeks and considered one of Missouri's most picturesque.

From there, I retraced my route until I came to Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park, on the East Fork of the Black River north of Lesterville.

Downstream, the water ran an obstacle course of rock, creating dozens of small waterfalls as it coursed over a thicket of smooth rhyolite slabs, creased and gray like an elephant's haunch.

Farther along, the waters of the 35-foot Deep Hole shimmered a gaudy blue-green.

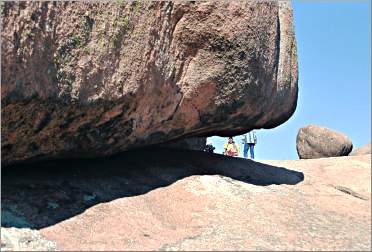

There were truly elephantine rocks not far to the north, in Elephant Rocks State Park. Eroded out of a massive granite outcropping, the largest, called Dumbo, is 27 feet tall and weighs 680 tons.

Other boulders resemble walruses, manatees and rhinos, and ecstatic children were swarming all over them.

"This is like kid paradise, isn't it?" said Jane Wease of St. Louis, who was staying at the nearby YMCA Trout Lodge with her family. "That's all they need, some rocks to climb on. Who cares about toys?"

Actually, Wease was having as much fun as her young daughters, climbing through "magic tunnels" between and under the gigantic boulders and slithering down the vast granite slab on which they sat.

© Beth Gauper

"I just love this," she said. "We could be here two weeks and not see every little crevice."

It was late in the day when I passed through Ironton, the county seat, and reached Taum Sauk Mountain State Park, home of Missouri's highest point. The 1,772-foot summit is just a small clearing in the woods, but from there a trail over loose rock leads to Mina Sauk Falls, the highest in the state at 132 feet.

Mina, according to legend, was a Sauk chief's daughter who loved an Osage. To prevent her from marrying him, her tribesmen lined a cliff with spear points and tossed him off.

Mina jumped after him, and the spirit god produced a great bolt of lightning that split the cliff and brought forth a gusher of water that washed away the blood of the lovers.

Sure enough, the narrow falls, crashing straight down from ledge to ledge, was as wild-looking as they come. I couldn't look long, however, for the light was fading, and only a few white blazes stood between me and a cold night on Taum Sauk Mountain.

I made it back to the lodge and instead spent the evening in front of a wood fire, in my rustic but comfy stone cabin on a hillside.

The area can't really claim to be "Missouri's best-kept secret" anymore, said Cody Wiles of Arcadia, though there still are many caves, shut-ins, trails and old mine sites that tourists overlook.

"There are so many natural features here," she says. "It's a gorgeous area."

Trip Tips: Missouri's Arcadia Valley

© Beth Gauper

Getting there : From St. Louis, it's two hours to hiking and canoeing sites.

When to go : April is a lovely month to visit, with no crowds, sunny days in the low 70s and cool evenings; however, cold and rainy days are possible. May and October are the prime tourism months, and the outdoor season extends into November.

For more about float trips, see Floating Missouri.

Summer can be hot and humid and is the time when city dwellers flock into the Ozarks, especially on weekends; rivers often are too low for canoeing, though not for tubing, and Mina Sauk Falls dries up.

Accommodations : In rural Lesterville, the Wilderness Lodge is a center for canoeing and has stone and timber cabins with kitchens, plus a lodge and outdoor hot tub, on 1,200 acres on the Black River.

Rates include dinner and a large breakfast, and box lunches are available. 888-969-9129.

In Lesterville, the Log Cabin Inn rents attractive modern units across the road from a canoe landing on the East Fork of the Black River, 573-637-2667. The Black River Chamber of Commerce lists other lodgings.

West of Potosi, an hour north of Ironton, the YMCA of the Ozarks Trout Lodge is a nice place for families.

Rates include three meals a day and activities: canoeing, hiking, archery, tennis, swimming, caving, pontoon rides, water slide and climbing tower with ropes program. Call 314-241-9622 or 573-438-2154.

Missouri Whitewater Championships : They're held in mid-March.

Recreational paddling : See Floating Missouri.

Missouri state parks and historic sites : 800-334-6946,

Information : Arcadia Valley Chamber of Commerce in Ironton, 573-546-7117; Missouri tourism, 800-810-5500.