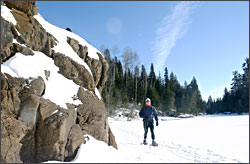

North Shore by snowshoe

In winter, hikers find serenity and stark beauty on trails above Lake Superior.

© Beth Gauper

In summer and fall, hikers by the thousands take to the hiking trails on Minnesota's North Shore.

In winter? Not so many. But those who strap on snowshoes to climb river gorges and follow the blue blazes of the Superior Hiking Trail are rewarded by stark beauty.

The brittle winter sun throws everything into high relief: Black lenticel pores seem to pop out on trunks of birch that are a brilliant white against the blue sky.

Sounds sharpen: the snapping and popping of trees in the cold, the crunch of snow underfoot, the grating croak of a raven. A coating of snow records the life — and often, death — of small animals.

One January, I snowshoed up to Carlton Peak on a 10-below day with 70-below wind chills. It was so cold the forest's trees were popping their skins, expanding as the moisture within them froze. The snapping sounded like the first raindrops before a thunderstorm.

But the wind never found its way to me through the trees, and I was warm in mukluks, snowsuit and fleece balaclava.

In less than an hour, I was winding my way around the darkened heel of the peak, a moonscape of ice and frozen lichen on a wall of granite, and up to the sunny summit.

Lake Superior, about 50 degrees warmer than the air, was steaming away 924 feet below; in the distance, I could see miles of hazy shoreline and a plume of vapor from the ore-processing plant in Taconite Harbor.

From the summit, the cold seemed rather exhilarating, and the rest of the three-mile hike was a cakewalk.

The next day was a little warmer, and I walked the five-mile Split Rock River loop. Newly fallen snow had frosted the fingerlike branches of baby firs and made the birches a paler shade of white.

Plump little cedar waxwings flitted around like Cinderella's helpers as I followed the packed trail, high above the open yellow mouth of the Split Rock River.

There was plenty to look at: a small, frozen waterfall into a creek, looking just like stalactites in a cave. Piles of chewed-up pinecones left by a squirrel. Deer tracks into the woods. Coyote scat, bristling with the hair of some small, unfortunate mammal.

© Paul Sundberg

Soon, I noticed rows of snowshoe tracks on the surface of the river and descended the banks. I could hear gurgling under the ice, but it was good and thick, and I walked upriver until the red-rock walls of the gorge trailed away into riverbank.

The trail returns on the east side of the river, but I followed the riverbed back, climbing back to the western spur along a beaver trail lined with toppled aspen.

On the highway, wind-sharpened flurries had replaced what, only a few steps inland, had been softly falling snow. I remembered something city people tend to forget: In the embrace of the forest, winter is much gentler.

Of course, that's not news to people who live on the North Shore. Ann Russ, a Tofte teacher and naturalist, loves winter for the serenity it gives to the forest and for what it reveals to those who venture there.

She shows it all to her students, from the tracks of animals invisible in other seasons to a birch tree's luminous peach underskin, unnoticed amid summer's greenery.

"I really get a charge out of taking people out, and oohing and aahing about what we see," she says. "The interesting thing about taking a walk in the woods is that we always see something, but we never know what it's going to be."

On a snowshoe hike in George Washington Memorial Pines, a small preserve just up the Gunflint Trail from Grand Marais, I could see the dramas of northwoods life sketched in the snow.

Rabbit tracks were everywhere, threading in and out of flocked heaps of downed boughs and, occasionally, meeting sets of larger tracks with a longer stride.

Just east of Grand Marais, I hiked atop the sheer, 100-foot walls of the Devil Track River gorge.

It was a good thing I had poles to help me grip the slippery inclines, because I was giving all my attention to the scenery — red-rock cliffs, frozen waterfalls, cascades of icicles.

Scenery is one thing the North Shore has in spades. For hikers, snow literally is the icing on the cake. Go and enjoy — just don't forget those long johns.

For other places to snowshoe around the state, see Snowshoeing in Minnesota.

© Beth Gauper

Trip Tips: North Shore by snowshoe

Events: The naturalist at Gooseberry Falls State Park leads many snowshoe hikes, and there's a candlelight skiing and snowshoeing event Presidents' Day weekend.

Split Rock Lighthouse State Park also offers hikes, some by candlelight.

Snow conditions: Check the Conditions page of the Superior Hiking Trail website for the latest news. Sometimes, the trailhead parking lots aren't plowed.

Snowshoe rental: At most resorts, use of snowshoes is free for guests. Gooseberry Falls State Park lends snowshoes for use during events; call in advance to reserve them.

Cascade Lodge between Lutsen and Grand Marais rents them, and so does Sawtooth Outfitters in Tofte.

Split Rock Lighthouse and Tettegouche state parks rent snowshoes for $6 per day.

For guests at many hotels and resorts, use is free (see Where to stay on Minnesota's North Shore. Be sure to take poles for climbs and icy spots.

Good snowshoe hikes: Any place with snow is a good spot. Sometimes, trails in state parks are so packed you don't even need snowshoes.

If there's not fresh snow, choose a spot off the beaten path, away from the state parks. The three-mile George Washington Memorial Pines preserve, six miles up the Gunflint Trail from Grand Marais, is a good choice.

A universal favorite is the Split Rock River Loop of the Superior Hiking Trail. The trail starts four miles north of Gooseberry Falls State Park, at the mouth of the Split Rock River; there's a parking area.

Not far from the trailhead on the west side of the river, there's a 20-foot blue-ice waterfall on a creek, around the corner from the first bridge. It's five miles up the west side of the red-rock gorge and back along a ridge on the east side and down through forest and wetlands.

© Beth Gauper

It's three miles round-trip to Carlton Peak from the Britton Peak parking lot, which is three miles up the Sawbill Trail (County Road 2) from Tofte.

From the same trailhead, you can snowshoe on the two-mile Oberg Mountain loop, popular in every season.

If you bring skis, you can return to Tofte on a wonderful 3-kilometer stretch of the Sugarbush Trail system known as the Tofte Ski-Down (see Skiing the North Shore ).

Five miles west of Schroeder, there's a one-mile interpretive trail through the Sugarloaf Cove preserve.

The trails that hug both sides of Cascade River State Park are scenic in every season.

To the Devil's Kettle in Judge C.R. Magney State Park, it's 2½ miles round-trip along the Brule River.

You can snowshoe along the Gitchi-Gami State Trail, which has an 17½-mile stretch from Gooseberry Falls State Park to Silver Bay, but much of it is open to the highway. Try the three-mile stretch through Temperance River State Park.

© Beth Gauper

Snowshoeing up rivers: You can snowshoe on a river itself, but be careful. Ask a local naturalist for advice, bring a buddy and carry a stick that you can tuck under your arms horizontally if you fall in.

Thick snow is no guarantee of safety; it's an insulator and may be keeping water from freezing.

Near Schroeder, there's a 1½-mile hike along the Caribou River past Caribou Falls to a bridge and back.

Three miles west of Lutsen, you can snowshoe through the slot canyons on the Onion River from the Ray Berglund Wayside parking area.

A 2.4-mile stretch of the Superior Hiking Trail follows the rim of the Devil Track River canyon, with views of the red cliffs and waterfalls below.

To get there, drive five miles north of Grand Marais to County Road 58 and turn; there's a parking area on the left.

It's 1½ miles round-trip up the narrow gorge of the Kadunce River from a wayside 10 miles north of Grand Marais.

For more, see Snowshoeing river canyons of the North Shore.