Chasing the Beargrease

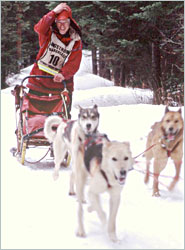

Along Minnesota's North Shore, the grueling sled-dog race enthralls onlookers.

© Torsten Muller

Long before reality shows turned survival into a stunt, there was John Beargrease.

With no fanfare and no road, the Ojibwe man delivered the weekly mail between Two Harbors and Grand Marais until 1899, using a dog team in winter. Using only four dogs to pull packs of up to 700 pounds, Beargrease could make the round-trip in a few days.

His stamina spawned a legend. Now mushers from around the nation come to trace his path, racing each other from Duluth to the Gunflint Trail in the John Beargrease Sled Dog Marathon.

For four days, they race around the clock, often running alongside their dogs and barely sleeping. But as grueling as the race is, it rewards not so much the strong as the canny — and the canines, because this race is all about dogs.

The Beargrease mushers are interesting people. But it's the dogs who sink a hook into innocent spectators, often turning them into helpless groupies.

Their spooky ice-blue eyes and maniacal energy make them mesmerizing to watch.

Seemingly too small and lean to pull anything, the dogs are bred for toughness and are as carefully trained, drilled and molded as Chinese gymnasts. At the Beargrease, announcers call them "canine athletes," not dogs.

Of the more than 900 canine athletes at the starting line of a Beargrease, at least 895 of them are literally at the ends of their ropes, jumping out of their skins with excitement.

Yelping as if in agony, they dance on their back feet as handlers struggle to hold them back. Some lead dog lurch ahead every two seconds like clockwork, until their ganglines finally go slack and their musher yells "Hike."

Then mushers hang on for dear life as their dogs explode down the fenced chute and around the first corner.

The sight of one team after another catapulting out of the starting line is one of the more thrilling sights in sports.

© Torsten Muller

A few minutes of watching this and spectators start to catch the bug: Who will come out on top? Who will fade? What will happen? Where can I watch some more?

Many people jump in their cars and follow the teams, staking out spots along the trail where they can see them go by.

"There are these little shelters up and down the trail for snowmobilers, and each one is full of people with hot dogs and hot chocolate," says Jack Welsh, a longtime volunteer coordinator who once kept a team of dogs. "Oh, yeah, it's contagious."

One year, my husband Torsten and I volunteered for Welsh at the Trail Center on the Gunflint Trail, so we could see more of the dogs and mushers.

After we watched the start, we drove up the shore and along the Gunflint Trail to the Poplar Creek Guesthouse, run by Ted and Barbara Young just across Poplar Lake from the Trail Center.

A musher himself, Ted competed in the Gunflint Mail Run, the predecessor of the Beargrease. Barb Young sewed the mailbags carried by racers, still a race tradition. They're both admirers of the 19th-century mailman.

"The Pony Express did it for 18 months; he did it for 20 years," Ted Young said.

On Monday morning, the Youngs gave us the latest race standings. Five teams already had reached the Sawbill checkpoint, where they had to spend six hours without help from handlers.

In the afternoon, we met Welsh and the other volunteers at the Trail Center to hang sponsor banners, haul wood for the bonfire and shovel snow to make a chute from the lake into the parking lot.

In the Trail Center, a former 1930s logging camp adorned with moose racks, old tin signs and antique saws, ham-radio operators listened for the latest news.

As we waited for the teams to arrive, the other volunteers, all experienced mushers, told us why the sport is so addictive.

© Heidi Pinkerton

"It's so fun," said Patty Prudden of Duluth. "The dogs are an extension of you; it's you and those little critters. There's so much trust."

"Out in the woods, it's so quiet," Welsh said. "They make a lot of noise when they start, but later they're quiet."

"That's why you can get so close to a moose and see the eagles," Prudden added.

A little after 7 p.m., we saw a headlamp winking across Poplar Lake; it was August Galloway, then a rookie from the Iron Range.

Her handlers already had shoveled out a chute in the snow near the lake and lined it with straw; her dogs ran right in and lay down, while Galloway cooked some watery mash over a little cook stove, fed them, covered them with blankets and rubbed their legs.

Galloway was followed by Frank Teasley, a mushing veteran from Jackson Hole, Wyo., and rookie Blake Freking. Liz Busa called out the time, I wrote it down and Torsten ran to get the bib number and count the dogs; mushers start with 14, and when one dog drops out, they cannot replace it.

Then Sally Bair had the musher sign a slip listing the time and number of dogs.

© Jason Mandich

Beargrease rookie Mary Black soon arrived, followed by Rachael Scdoris, a legally blind young woman from Bend, Ore., who was negotiating the turns with the help of a friend, running just ahead of her with a two-way radio.

We went in for dinner around 10 p.m., then returned to the bonfire to wait. John Stearley had driven 17 hours from southern Indiana to watch the race and spend two weeks at his cabin on the edge of the BWCA. At first, he said, the family came only in summer.

"Then one day my son said, 'I wonder what it's like in winter,' " Stearley said. "I said, 'Oh, you don't want to come in winter, it's brutal.' But we came so I could teach him a lesson, thinking he'd be turned off, but we were both turned on."

For a while, all was quiet. But Busa said there was plenty going on that we couldn't see.

"The people at the top of the pack watch each other like mad," she said. "When the mushers are sleepin', the handlers are spyin'."

At 1 a.m., Freking walked up and quietly asked for a bag check at his camp; before mushers leave a checkpoint, volunteers must verify that their bags contain mandatory gear, including the mailbag, two headlamps, rations and safety equipment.

It bought him a few minutes, but by the time he left, his dogs were howling and the other mushers knew the game was afoot.

It rattled Frank Teasley, a previous Beargrease winner, who left after checking Busa's watch and arguing with Bair about timing. Then veteran musher Keith Aili left, followed by Galloway.

No one budged after that, and we left the checkpoint to the regulars, happy to sit into the wee hours.

The next day, we strapped on snowshoes and spent the afternoon in the Boundary Waters, using canoe portages to travel from the glittering white expanses of Caribou Lake to Lizz Lake and then back to Poplar and the Banadad Trail.

We returned to the Trail Center for dinner Tuesday evening. Proprietor Sarah Hamilton was at the front desk feeding her Rottweiler puppy a plate of Alaskan pollock and sauteed veggies. She still hadn't been to bed after the big night, but she looked happy.

© Torsten Muller

"The Beargrease started up here, just a bunch of locals having fun," she said. "Then somebody took it over and took it to Duluth, and they didn't even know it was our idea. So we're thrilled to have it back here."

On Wednesday morning, the Youngs handed us a printout. By the next to last checkpoint, the status quo was holding: Freking, Teasley, Aili, Galloway, Black.

When we got back to Duluth, we heard Freking had easily won with his team of Siberian huskies, seldom-used race dogs that Jack Welsh had earlier dismissed as "Slow-berians."

"I didn't notice how many dogs he had left; I was too busy eating my words," Welsh said with a smile.

Freking had pulled what race coordinator Alex Angelos called a "Jamie Nelson" move, after the four-time Beargrease (1988, '95 and '97-'98) winner: Stay a few places back, make sure your dogs get plenty of rest, then move ahead on the downbound leg, forcing other mushers to change plans.

"If you can pull the other mushers off their strategy, things start to unfold, and they might make some changes," Angelos said. "Sometimes it works to their advantage, but usually it doesn't."

© Torsten Muller

Aili came in more than two hours later, followed by Teasley and Mary Black. But Galloway's dogs had gone on strike not far from the finish, and she had to scratch.

"She made the typical rookie mistake, running her dogs too hard off the start," Welsh said.

But he had to eat his words again when Rachael Scdoris arrived, not only placing sixth but coming across the finish line with nine of her original dogs, more than any of the other top finishers.

"Every race has a little different flavor," says Angelos, longtime race coordinator and now a race judge.

Angelos uses the same word everyone does to describe the Beargrease: addictive.

"I've been out long enough that you get the bug, and then you feel dangerous: 'I could do that,' " he says ruefully. "And then you work a while as a volunteer and a handler, and you realize, there's no way I could do that."

Trip Tips: John Beargrease Sled Dog Marathon

Getting there: The race was shortened in 2019 and now starts at Billy's Bar on the edge of Duluth and ends in Grand Portage Lodge & Casino, a 300-mile race.

The 120-mile race ends at Lutsen Mountains, and the 40-mile race ends in Two Harbors.

Check conditions before you go. To get to Billy's, take Superior Street to 43rd Avenue East and go left to Glenwood Avenue. Take a left at Glenwood and go to Jean Duluth Road. Take a right at Jean Duluth Road and drive to Tischer Road.

There's a free parking and a shuttle from the University of Minnesota-Duluth Lot W in Duluth.

Race events: The race is held the last Sunday in January, with events all weekend. On race day, spectators can meet the mushers at 8 a.m. The race starts at 10 a.m.

Marathon mushers leave first, followed by the 120 and then 40 racers. The first musher is expected to reach Grand Portage late Tuesday afternoon.

Be sure to buy a program. It includes the bib numbers of the mushers, which you'll need to know whom you're seeing farther down the route.

Watching along the route: Because mushers can choose how long they will spend at most checkpoints, it's hard to predict when they'll arrive at any one place. Temperatures also affect the race; when it's warm, mushers try to run mostly at night, when it's cooler.

It's essential to dress warmly if you'll be standing around waiting. Wear twice as much as you think you'll need and bring chemical hand and feet warmers, available at hardware and home-supply stores.

Volunteering: Nearly 1,000 volunteers are needed to do everything from tabulating "Cutest Puppy" votes to moving sponsor banners up and down the trail to helping teams cross highways.

Information: Beargrease, 218-722-7631.

For information on other things to do in the area, see Relishing winter in Duluth.