Magnificent obsessions

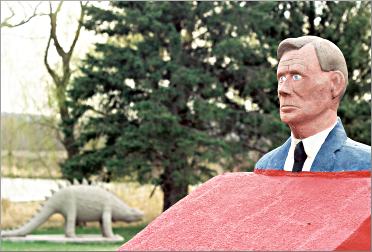

In the Wisconsin countryside, self-taught visionaries left caches of concrete art.

© Beth Gauper

In Wisconsin, nonconformity is cast in concrete.

In the middle of the last century, a motley collection of ordinary folk — a dairy farmer, a car dealer, a tavern owner, a factory worker — took a sharp turn away from the ordinary.

Out of the blue, they began to fashion fairy-tale characters, castles, temples and historical figures out of concrete, adorning them with bits of glass, crockery, porcelain and seashells and toiling until their yards overflowed with figures.

Why? Because they felt like it. Long before the New Age dawned, they had learned to follow their bliss.

The fruits of their labor can be found from the shores of Lake Michigan to the Mississippi River, along highways, in the wooded yard of a summer cottage and at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan.

Today, thousands of people come from all over the world to marvel at the artists' originality. They weren't prodigies or geniuses, but what these self-taught artists lacked in polish, they made up for in sheer exuberance.

"I just love the passion," said Terri Yoho, who, as executive director of the Kohler Foundation, helped restore the sites. "When someone does something just because they want to, and they don't care about anybody else, or money, it's so real and pure."

For many, creating art was an antidote to tedium.

Herman Rusch, a retired farmer who created Prairie Moon along the Mississippi, called it "a good way to kill old-age boredom."

Dairy farmer Nick Engelbert, who created Grandview in the hills of southwest Wisconsin, and furniture painter James Tellen, who filled the yard of his cottage near Lake Michigan, both started creating figures after they had been waylaid by illness.

© Beth Gauper

And it was a way to pay tribute to people and things close to their hearts.

In the countryside near Sparta, Wis., car dealer Paul Wegner had retired and didn't want to hunt or fish. So, inspired by a visit to the Dickeyville Grotto in the state's southwest tip, he and wife Matilda came home and built a glass church.

Then, they fashioned an American flag, a replica of their 50th-anniversary cake, a big white heart, a star and the Bremen ocean liner, which reminded them of the one on which they had emigrated from Germany.

After Paul died in 1937, Matilda kept working on the Wegner Grotto.

In the north woods, former lumberjack and tavern owner Fred Smith started building figures of people he liked or admired — he filled the yard of his tavern with 203 figures, which he called the Wisconsin Concrete Park.

His neighbors in Phillips, Wis., thought he was a crackpot, but the flamboyant Smith didn't care: "I've been having a good time all my life!" he said, even after a 1964 stroke forced him into a rest home.

The work was good for their souls — and today, it's good for ours.

© Beth Gauper

True originals

In a mass-produced world, their idiosyncratic visions are like a breath of fresh air. I visit them whenever I can.

Driving along the Mississippi on Wisconsin 35, I always stop at Prairie Moon Sculpture Garden and Museum, where Rusch installed a Hindu temple, a crenellated stone watchtower and three dozen other concrete sculptures, including a colorful arched fence with conical tips painted gold.

Driving between my favorite towns in southwest Wisconsin, Mineral Point and New Glarus, I stop at Grandview, where whimsical figures populate the rolling yard of Nick Engelbert.

There's an organ grinder, a Viking in a boat, Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, a Hapsburg castle, King Neptune and the Family Tree that depicts his own four children as monkeys.

© Beth Gauper

One of the newer sites preserved by the Kohler Foundation is the Tellen Woodland Sculpture Garden, in a quiet neighborhood on the outskirts of Sheboygan.

James Tellen worked in a furniture factory, painting decorative details. In 1942, in a hospital recovering from an illness, he was inspired by the concrete sculptures he could see in the churchyard across the street.

For the remaining 15 years of his life, he created concrete figures for the yard of his log summer cottage, often displaying the sly humor seen at Grandview.

Unlike Smith, Tellen had the encouragement of his friends and family, and his 1957 obituary in the Sheboygan Press called his sculpture environment "one of the finest exhibits of outdoor art in the state."

"He stands away from the others," Yoho said. "He was a businessman, more mainstream than some of the other artists. And he was very well read, with a lot of respect for history and his religion."

© Beth Gauper

Rescue missions

For decades, the Kohler Foundation in nearby Kohler has painstakingly preserved such works; since the artists created them for themselves, not posterity, most had fallen into nearly irreparable states of decay.

It also has rescued sites outside Wisconsin, such as one in Chauvin, La., where an enigmatic man named Kenny Hill left more than 100 concrete sculptures along a bayou.

"That was magical, and nobody knew about it, not even in the town where he did it," said the late Ruth DeYoung Kohler, who was the longtime president of the Kohler Foundation and director of the John Michael Kohler Arts Center, which occupies her grandfather's former home in Sheboygan.

"They needed someone to say, 'This is important.' Fred Smith was the first, and when we first went up to talk to him, his family was talking about razing the place."

Smith's will specified if the figures weren't moved, they belonged to the tavern, which had been sold. When they went to Phillips to move the heavy figures, Kohler said, the tavern owner put up mounds of dirt to block the DNR front-end loader and gave away free beer so customers' cars would clog the parking lot.

© Beth Gauper

But Kohler and her crew succeeded in moving the figures across the lot line, where they were restored and remain today.

"Even that first day, people began to think about them differently," she said. "Some even stayed to help us. There was a change in the mind set."

Now, the Wisconsin Concrete Park is world-renowned, drawing thousands of visitors yearly.

Even though the Kohler Foundation's goal is to allow local people to take over after restoration is complete, Yoho said it never loses contact.

"It's like a child who goes off and gets married and has a life of its own," she said. "That doesn't mean you forget about them."

The Kohler Foundation continues to go to great lengths to preserve great examples of outsider art, which is what curators call it. Another project had to be retrieved from a Minnesota antiques dealer and the various people to whom he had sold or consigned the life work of Carl Peterson.

A blacksmith and cabinetmaker, Peterson also was a self-taught artist. Between the turn of the century and 1937, he created an Environmental Sculpture Garden of Nature in the southwest Minnesota farm town of St. James.

"We got a call from a friend at the Art Institute in Chicago, who said, 'There's some really cool stuff going up for auction in Maine Tuesday, I think you'd like it,' " Yoho said.

"So we bought all the pieces available, and then we tracked down the consigner, and he had some of the rest, including a 45-foot flagpole, a birdbath and eight or 10 miniature concrete castles.

"Then we sent an intern to St. James to look around, and we paid some people to let us excavate, and we found some old rubble and pieces. We started putting things together, and suddenly the castles are fitting together like a village. So what had been the size of a doghouse suddenly became much bigger, with unbelievably constructed pieces. It was done with such incredible care; it's mesmerizing."

The center has more than 50 pieces, and 15 of the large-scale works are displayed in its gardens.

"We feel bad that we had to take them out of state; we feel really bad," Yoho said. "But we feel really good that we're able to preserve them. Everyone here has become very attached to them."

Trip Tips: Wisconsin art environments

Many pieces can be seen in and around the wonderful John Michael Kohler Art Center in Sheboygan.

For more photos and descriptions of the art environments, see Road trip: Wisconsin's concrete art.