Road trip: Southwest Wisconsin

A 170-mile loop winds past lead mines, a famous grotto and a brewery town.

© Beth Gauper

Scratch the surface in southwest Wisconsin, and you'll find treasure.

In the 1820s, it took the form of lead ore that early miners, to their amazement, found at the grassroots. Lead and zinc made this area bustle when Milwaukee and Madison were just getting started, and one of its villages served as the territory's first capital.

Today, visitors to this corner of the state — just across the Illinois border and up the Mississippi bluffs — find a lode of history in a beautiful landscape.

A 170-mile loop tour takes it all in: a hill that appears to violate the law of gravity; a church built by a revered frontier priest; a famous grotto; a brewery town from the "badger" era; a rediscovered 1845 lead mine; and the territory's first capital.

Starting in Mineral Point

The entire downtown of this lovely village is a national historic district, and stone cottages built by Cornish miners are part of the Wisconsin Historical Society's Pendarvis, where costumed guides give tours.

Merry Christmas Mine was right across Shake Rag Street, which supposedly was named for a mealtime ritual: When women in the cottages had dinner ready, they'd wave a dish towel to catch the attention of the miner working atop the hill.

"Mineral" first was found at the point where two streams converged, and an old zinc-smelting chimney rises above nearby Ted's Pond. Today, this pastoral spot near the end of Commerce Street is home to a cluster of inns and restaurants.

The town is home to many artists, who have opened galleries and studios along its hilly streets. For more, see Beauty in Mineral Point.

Gift shops and Gravity Hill

Heading south on Wisconsin 23, you'll go through Darlington to reach Shullsburg, where mining continued until 1979.

It has weathered the full cycle. Solo miners came first, digging the "badger holes" that inspired Wisconsin's nickname, followed by corporations that pulled up millions of tons of lead and zinc ore. Eventually, a drop in demand and new environmental standards closed the mines.

But Shullsburg was left with a handsome collection of brick storefronts from the 1840s. It would like to emulate another lead-mining town that lined its main street with shops and became a tourist favorite: Galena, just across the border in Illinois.

© Beth Gauper

It's a rose-colored vision to match the town's rose-colored sidewalks, adorned with old-fashioned lampposts. Along Water Street, attractive shops sell gifts, cheese, kitchenware, primitive furnishings and bags of chocolate "tailings," the rock debris from mining.

At the Badger Mine & Museum, tours include a descent into a hand-dug 19th-century mine.

From downtown, drive south to Gravity Hill, at the foot of two hills. Put your car into neutral and see if your car starts rolling up the hill.

Then head west on Wisconsin 11, past the site of the big Calumet and Hecla mine, the last to close in 1979. A pile of tailings marks the Mulcahy Mine, where eight men died in a 1943 cave-in, the worst mining accident in Wisconsin history.

The landscape is lumpy here, its rocky skeleton breaking through a thin skin of vegetation. The hills of Illinois rise only three miles to the south, and the official Illinois high point is just across the border, near the village of Scales Mound.

Father Mazzuchelli's church

Just south of Wisconsin 11 in New Diggings, a weathered frame general store/bar and a few houses are almost all that remains of the early boom town.

But up the hill, there's one thing more — St. Augustine Church, built in 1844 by Father Samuel Mazzuchelli.

© Beth Gauper

This revered Italian priest — called Father Michael Kelly by his Irish flock — founded 40 parishes and built 17 churches between Mackinac Island and Muscatine, Iowa.

This one he built with hammer in hand, notching the wood planks to resemble the stonework of churches in his native Italy, complete with dentils and moldings.

The priest is being considered for sainthood, and George Burns, a member of the Mazzuchelli Awareness Campaign, said its existence should count as one of the required miracles: "For it to be still standing, without any alteration, in an isolated place like this — that's a miracle."

Three miles west of New Diggings off County Road W, drive the pastoral, 7½-mile Rustic Road 66, which follows the Coon Branch of the Galena River, a twisting gash in the flat coulee floor, and past the tunnel of an old rail line.

An inspiring shrine in Dickeyville

The old Illinois mining town of Galena, named for lead ore, is only nine miles south of the old stagecoach stop of Hazel Green. From there, head north to Cuba City and west to Dickeyville.

Between 1925 and 1930, a German-born priest named Mathias Wernerus built Holy Ghost Park, popularly known as the Dickeyville Grotto. It became a tourist attraction and largely inspired the rich tradition of sculptural expression in Wisconsin and around the region.

The series of grottos and shrines is made of concrete embellished with rose quartz, geodes, petrified wood, colored glass, china and other treasures that the priest and his parishioners scavenged from around the nation.

© Beth Gauper

They topped it off with American flags and eagles, to demonstrate loyalty to country as well as church.

The Dickeyville Grotto is part of another interesting tour of cool roadside attractions: Road trip: Wisconsin's concrete art.

Badgers and beer in Potosi

From Dickeyville, head west to Potosi, where a pockmarked hillside preserves remnants from the state's earliest days. Across from the St. John Mine, the Badger Hut Trail leads past outcroppings of dolomite and limestone — a sign to early prospectors that lead might be nearby — to two huts.

They're circle-shaped piles of rubble today. But they weren't that much nicer in the 1830s, when they had sod roofs that leaked on the miners inside, making them about as grumpy as the mammals for which they're named.

The state could have a worse nickname: "Badgers" were the miners who dug in for the winter, but the ones who migrated south were called "suckers," after the fish.

Halfway up the opposite hillside is Snake Cave, where it's said local Indians first showed lead to French explorer Nicolas Perrot around 1690.

A century later, across the river, the Mesquakie band befriended French-Canadian fur trader Julien Dubuque, who married Potosa, daughter of a chief, and made a fortune mining lead on their land.

In Potosi, St. John Mine was dug under the floor of Snake Cave in 1840. Its walls were covered with flowstone, onyx and chert, or flint. But the miners were looking for something else, using candlelight to catch the gleam of galena, or lead ore.

Potosi also is a long-time brewing town. The Potosi Brewing Co. started in 1852 and became the fifth-largest brewery in Wisconsin, in later years producing Holiday, Garten Bräu and Alpine Lager.

It closed in 1972 but reopened in 2008 and now is run by a foundation. The restored brewery includes the American Breweriana Association's National Brewery Museum, the Potosi Brewing Co. Transportation Museum and the Great River Road Interpretive Center.

There's a handsome brew pub and a pretty beer garden out back.

And of course, there's freshly made beer: the flagship Good Old Potosi farmhouse ale as well as Snake Hollow India pale ale, Potosi Pure Malt Cave ale, half a dozen seasonal brews and, for the kids, Princess Potosa root beer.

© Beth Gauper

Underground in Platteville

From Potosi, take Wisconsin 35 north, then County Road B east to Platteville, where the nation's first mining school was founded in 1907.

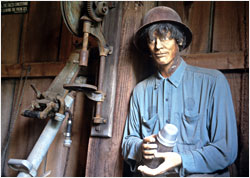

In the middle of town, an 1845 lead mine was rediscovered under a schoolhouse in 1972 and now is part of the Mining Museum, where guides explain what life was like underground.

Visitors descend 90 steps into the mine and hear a classic get-rich story: Lorenzo Bevans, having failed at law and shopkeeping, was bankrupt and living on credit when he asked a prominent mine owner if he could dig on his land.

He found nothing for months and was about to give up when he hit a vein that yielded 2 million pounds of ore the first summer. He promptly got out of the mine business and opened another general store.

It was a wise decision: By the time miners were in their 40s, they suffered from poor eyesight, bad knees, chronic coughs and, of course, lead poisoning.

Life-size mannequins portray the men who toiled by candlelight; one of them is black, representing the slaves who were sent north to work in Wisconsin mines.

Outside, visit the hoist house, where ore was lifted out of the shaft and sorted, and ride around the grounds behind a 24-gauge locomotive that once pulled 1,500-pound ore cans.

Many similar mines lie under the streets of Platteville, the region's largest town, and until the 1950s, when people sold their houses, they would maintain the mineral rights.

The Wisconsin Mining Trade School grew into UW-Platteville, whose students created and maintain a 241-foot-tall white "M" on a hill east of town — the largest "M" in the world.

The forgotten First Capitol

Off U.S. 151 just east of Platteville, you'll find Belmont. In 1836, thanks to lead-mine owner Henry Dodge, this village became the first capital of Wisconsin Territory, which included all of present-day Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa and part of the Dakotas.

Today, Belmont barely exists, though the Wisconsin Historical Society still preserves the two lodging houses into which 39 legislators squeezed, hammering out a legal and judicial framework in 46 days.

Henry Dodge became the first territorial governor, and Nelson Dewey, who also became a lead-mine owner when he bought Potosi's St. John Mine, was the first state governor.

The California Gold Rush soon led to the first bust in the lead-boom cycle, siphoning off local miners. Then the rest of Wisconsin grew up, making the state famous for other things: motorcycles, paper, outboard motors, beer and cheese.

But in this niche of Wisconsin, the landscape still stands testament to those who took the lead.

Trip Tips: Southwest Wisconsin mining country

© Beth Gauper

Pendarvis in Mineral Point: Costumed interpreters give tours of the restored miner's cottages from Thursdays-Sundays from late May through mid-October.

For more, see Beauty in Mineral Point.

Badger Mine & Museum in Shullsburg: It's open Wednesday-Sunday from Memorial Day through Labor Day.

Gravity Hill: From Shullsburg, drive south on County Road U two miles, past Rennick Road. Stop just short of the farm-field gate on the right and put car into neutral. Watch for other cars.

National Brewery Museum in Potosi: It's open daily.

Mining Museum/Rollo Jamison Museum in Platteville: It's open Wednesdays-Sundays from May through October. It's at 405 E. Main St., just east of downtown.

First Capitol in Belmont: It's open weekends from Memorial Day through Labor Day weekends. Admission is free.

Accommodations: There are many good places to stay in Mineral Point.

Shopping: Mineral Point, Darlington and Platteville have Bargain Nooks, non-profit resale stores that carry mostly cut-rate Land's End catalog returns.

Information: Shullsburg and Grant County tourism (Dickeyville, Potosi, Platteville).