Baraboo's gilt complex

In Wisconsin's Ringlingville, the golden age of the circus never ended.

© Beth Gauper

In the circus, nothing succeeds like excess. And no one succeeded at that more than the Ringling brothers.

In the last half of the 19th century, Americans clamored to be amazed. Tent shows traversed the countryside; Wisconsin alone had more than 100.

On the Mississippi, showboats brought entertainment to river towns. In 1869, two circuses — one was Dan Rice's Own Circus, whose proprietor's clown character was the inspiration for Uncle Sam — put on performances in the Iowa river town of McGregor.

They enthralled the 17-year-old son of a poor German harness maker.

With his brothers, Al Ringling started to put on acts for the locals, and eventually spent seven years traveling with other shows.

In 1884, he and four brothers set up their own tent in Baraboo, Wis., to which the family had returned nine years before. Al balanced a plow on his chin, and John danced in wooden shoes.

The brothers ran a tight ship — their circus was called a "Sunday-school show," because it kept out swindlers and welcomed children — and it grew. In 1889, it took to the rails, competing with Barnum & Bailey's Greatest Show on Earth.

This was the golden age of the circus. Lavish "spectacles" used costumed casts of 1,000. Menageries overflowed with lions and tigers and bears — and elephants by the dozen.

Circus wagons were eye-popping, each one a riot of gilded cherubs and eagles and bare-breasted women.

It was a giddy age, too. The public had an appetite for the exotic, and it was inflamed by the hyperbole of advance men, who would bill Hindu dancers, for example, as "beautiful wild Moorish bayadires, in bewitching dances to the music of native derboukas and flutes."

Each winter for 35 years, the Ringling brothers brought their circus back to Baraboo, repairing wagons, training animals and developing new acts in a riverside complex of 30 buildings that became known as Ringlingville.

In 1907, they bought their rival and became the biggest circus operation in the world.

© Beth Gauper

Today, the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Greatest Show on Earth still is the biggest. But the golden age — before movies and television made the exotic ordinary — is over.

Except in Baraboo.

Calliopes still blast away in Baraboo. Aerialists spin on ropes, and a ringmaster spins hyperbole.

Gaudy props and costumes from bygone spectacles fill an exhibit hall, and a pavilion houses the world's largest collection of circus wagons, some of them still loaded daily onto rail cars.

This is Circus World, a 50-acre complex on the old Ringlingville site that appeals to what John Ringling called "the universal instinct to be young again."

In the summer, circus performers come from all over the world to perform and live at Circus World, owned by the Wisconsin Historical Society.

When I brought my kids to Circus World, we met Karen and Greg DeSanto, who were directors of clowning for Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey at the Sarasota, Fla., winter quarters.

"Here, they really keep tradition, and we can do just good classic clowning," said Karen DeSanto, an auguste clown in the style of the legendary Lou Jacob. "The (regular) circus is very theatrical now. In this Lazer Tag era, it's hard to make people watch simple people do extraordinary things."

It wasn't hard to watch the DeSantos. As Prickly Pete and Polly Pureheart in a Western sketch and the Swami and his subject in a hypnotist skit, the two clowns were hysterical, leaving my son Peter convulsed with laughter.

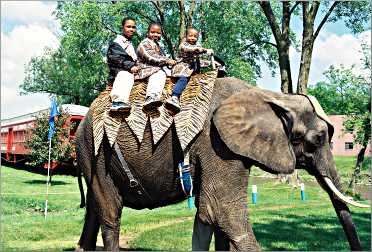

My daughter Madeleine was transfixed by the children who performed: a 12-year-old from Russia who performed aerial feats on two canvas straps; 10- and 8-year-olds who rode elephants; and a 3-year-old who rode a tiny unicycle with the help of his juggler father.

During our day at Circus World, we did everything we could. We tossed balls in the You Can Juggle demonstration and fed carrot coins to giraffes and camels. We saw the Big Top Circus and its "awe-inspiring performances that reach beyond the limits of human endeavor."

"Just as it did 100 years ago, this sawdust ring will create memories that will last a lifetime," announced the charismatic ringmaster in a rich baritone.

Two young women from Kazakhstan performed aerial feats on a rope, twisting their limbs every which way, and the enchanting Juliet twirled hoops. Another juggled with her feet, and the clowns got silly with strategically placed balloons.

© Beth Gauper

My favorite act was strong man Vladimir, a Russian in a Roman gladiator's outfit who balanced an enormous barbell on his head and juggled three silver spheres, letting one land on his back and slide down his arm.

To prove their weight, he tried to give one to a man in the front row, who couldn't hold it even for a second.

We watched a movie about the Ringling brothers, seven of whom eventually worked for the circus, and toured the exhibit barns, where we saw a 30,000-piece miniature circus and Emmett Kelly's hobo wardrobe.

In the Hippodrome, we saw the Razzle Dazzle Revue, a vaudeville-style "after show."

After T.J. Howell's unicycle act, Peter grabbed my arm. "This place rocks, big time," he said, his eyes still glued to the stage.

We watched the performers waving atop elephants and circus wagons in the street parade and went to the Elephant Encounter, where we got to stroke Makita, her small eye blinking under a long, long eyelash.

"Elephants are really capable of doing anything we ask them to do," said her trainer, Jorge Barreda. "Once they understand what you want them to do, they never forget. Their memory banks are three times larger than a human's, so it really is true that an elephant never forgets."

The elephants now have been retired from performing.

And we went to Karen DeSanto's Be a Clown class, where a young boy won the chance to be made into her auguste twin, complete with white greasepaint and red bulb nose.

"They're like the only non-scary clown I've seen," Madeleine said afterward. "The way she described the circus, I think it'd be fun."

In fact, Madeleine was a little peeved when I reminded her she hadn't wanted to visit Circus World, thinking it nothing but a kiddie show.

"I guess this is pretty cool after all," she said. Not boring? "No!" she said, shocked. "Not boring at all."

Trip Tips: Circus World and Baraboo, Wisconsin

© Beth Gauper

Getting there: It's 20 minutes south of Wisconsin Dells and 45 minutes northwest of Madison.

Circus World Museum: The circus performance season begins in May and runs through Labor Day. Exhibit halls are open year-round. It's open daily from mid-April to late October, weekdays in winter.

Events in Baraboo: May, Spring Fair on the Square. June, Art June. June, Big Top Parade & Circus Celebration. August, Badger Steam & Gas Engine Show. October, Fall Fair on the Square. October, Southwest Wisconsin Fall Art Tour.

Accommodations: The Ringling House B&B, in a Georgian Revival mansion built in 1900 for Charles Ringley, has six rooms.

Baraboo has several motels, among them the Best Western Baraboo Inn.

On the southern edge of town, the Willowood Inn is close to Devil's Lake State Park. It's a neat and comfortable mom-and-pop motel with 15 units and a two-bedroom cottage with kitchen. Three units are available for pets. There's a fire pit in the back yard, grills, a playground and a heated outdoor pool.

Nearby Wisconsin Dells also has many accommodations.

For more, see The quiet side of the Dells.

Dining: The Little Village Cafe on Courthouse Square is a good place to eat, 608-356-2800.

Jose's Authentic Mexican Restaurant is on the northeast side of downtown, at 825 Eighth St.

Near the north entrance of Devil's Lake State Park, Tumbled Rock Brewery & Kitchen serves wood-fired pizza, steak and fish. It has a patio and a lawn for games.

© Beth Gauper

Shopping: There are many interesting shops on Courthouse Square, including Bekah Kate's, which sells gourmet cookware and holds cooking classes.

Nightlife: The palatial 1915 Al. Ringling Theatre in Baraboo offers concerts, plays and national acts.

Nearby attractions: Gorgeous Devil's Lake State Park, the most-visited state park in Wisconsin, is three miles south of Baraboo and has a beach and 30 miles of hiking trails.

The five-mile hike around the lake on the West Bluff and East Bluff trails, part of the Ice Age National Scenic Trail, is perhaps the most spectacular hike in Wisconsin.

For more, see The divine Devil's Lake.

The International Crane Foundation is three miles southeast of the junction of I-94 and U.S. 12.

For more, see Cranes of Wisconsin.

For more about Baraboo-area naturalists, see Pilgrimage to the Baraboo Hills.

Ten miles west of Baraboo in North Freedom, the Mid-Continent Railway Museum runs excursion trains daily through summer and on autumn weekends; there's a snow train in February.

Information: Baraboo tourism, 608-448-3490.