Scenes from the fur trade

At re-created forts, meet the adventurers who shaped the Upper Midwest.

© Beth Gauper

Long before settlers plodded into the Upper Midwest, its rivers and forests were swarming with a more footloose kind of entrepreneur.

The Pilgrims still were getting a toehold on the eastern seaboard when Frenchman Jean Nicolet passed through the Straits of Mackinac in 1634 on his way to Green Bay, returning to Montreal with news of a vast interior filled with fur-bearing animals.

Traders wasted no time going after the pelts, and international commerce already was brisk by the time people in Salem, Mass., were whipping themselves into a frenzy over imagined witchcraft.

Profit was a powerful motivator: Scottish fur trader Alexander Mackenzie had made his way across the continent to the Pacific a full decade before Lewis and Clark left St. Louis, carrying a copy of Mackenzie's travel journals.

There were no towns to speak of, but plenty was going on in the north woods.

North America's first million was made off the back of the almighty beaver, whose pelts were called "soft gold" and prompted the formation of one of the first modern corporations, complete with lobbyists, centralized management, mergers and buyouts.

Men's fashion shaped the continent for the first 200 years after Europeans penetrated its interior. High-society demand for felt top hats, made from the barbed fur of the beaver, changed the lives of everyone from Ojibwe hunters to the French emperor.

Local schoolchildren today are more likely to read about Paul Revere than Pierre Radisson, because the French are gone, along with the Scots and English.

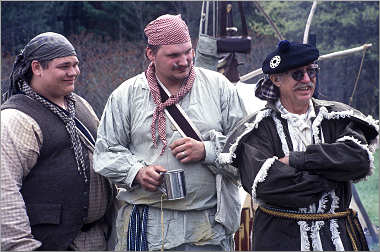

Yet redcoats and blackrobes once roamed right in our back yard, along with traders and a colorful cadre of voyageurs.

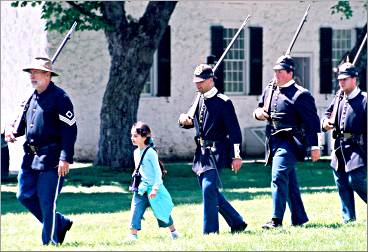

These characters live on in historical sites around the region, where re-enactors don the scarlet waistcoats of British soldiers, the flowing black cassocks of Jesuit priests and the striped shirts and sashes of the French-Canadian farm boys recruited to paddle the canoes and carry the packs.

© Beth Gauper

At Grand Portage National Monument on the northeast tip of Minnesota, costumed interpreters take visitors around a re-created Great Hall, Ojibwe village and canoe warehouse.

Grand Portage was the center of the Great Lakes fur trade until 1803, when the North West Co., run by the British, had to pack up and move across the border, 42 miles north of present-day Thunder Bay.

There, they built Fort William, which the Ontario government has re-created as Fort William Historical Park. Fort William is the continent's largest reconstructed post, with 42 buildings on 20 acres. Interpreters go about their business as if it's just another day in 1815.

When I was there, we heard a dramatic quarrel in the council house over voyageur contracts, illicit trading and the tactics of Lord Selkirk, whose Red River colony was threatening trade; the next year, North West Co. men massacred 22 people at the colony, and Selkirk seized Fort William.

There is less drama but as much history on the Yellow River in northwest Wisconsin, where an Ojibwe village and posts of the North West and XY companies have been rebuilt on the spot where they stood between 1802 and 1804.

Today, it's Forts Folle Avoine Historical Park, where costumed interpreters lead tours of the village and posts.

John Sayer was the North West Co. wintering partner, and the next year, he headed down the St. Croix River and up the Snake River to a spot near Pine City, where he and eight voyageurs built another post.

That, too, has been rebuilt and is now the Snake River Fur Post, run by the Minnesota Historical Society.

The last time I was there, I was greeted in French by Francois Boucher, the post's voyageur foreman, and shown around by Guillaume, a first-year voyageur.

Later, I chatted with Bedowekque, a métis woman with an Ojibwe mother and voyageur father, as she repaired moosehide moccasins.

© Beth Gauper

Sayer wasn't there; in real life, he moved on to Fort William the next year, leaving his children and the Ojibwe wife whose family connections had furthered his career.

One June, I visited another pair of fur posts on the Straits of Mackinac, in Michigan. Everyone in the fur trade had to pass through here, and many began their careers; John Sayer got his start working as an apprentice clerk at Michilimackinac.

Michilimackinac — the name is a French corruption of an Indian word describing Mackinac Island — was built on the south shore of the Strait of Mackinac by the French in 1715 and taken by the British in 1761, after victory over the French in the French and Indian War.

Today it's been rebuilt on the same flat, sandy site, in the shadow of the Mackinac Bridge. Within the palisades of Colonial Michilimackinac, interpreters portray the year 1775, when the King's Eighth Regiment was posted there.

It was a fur depot as well as a military post, and at any time Ottawa, Ojibwe, French-Canadians, métis, Scots and German Jews could be seen on the streets conducting business.

© Beth Gauper

I got there during the Arrival of the Voyageurs re-enactment, as a tourist family was donning stocking caps and sashes to help distribute trade goods. Archaelogists were near the gardens excavating, as they have been since 1959, and a British sergeant was giving a musket-firing demonstration.

"Imagine thousands of these going off every 20 seconds in an open meadow; it makes a lot of smoke," he said. "That's one of the reasons the British wore red coats, so they could see each other."

On a wet day muskets were unreliable, he said, and he showed how troops would "set bayonet," turning their muskets into a 7-foot spear coated in sulfur dioxide from gunpowder residue.

"The bayonet was more feared," he said. "If you were even poked in the hand, you could die of blood poisoning."

An Ottawa interpreter explained how the coveted trade goods changed tribal lifestyles, creating dependence on the Europeans.

In St. Anne's chapel, we witnessed a French ceremony in which visiting priest Father Gibeault married one of the fort's Indian interpreters and his bride from a prominent family in Detroit.

In 1781, during the American Revolution, the British burned the fort to the ground and built another on Mackinac Island, which could be better defended.

After 1783, it technically belonged to the Americans, but they were unable to take control until a treaty in 1796.

The British took it back in the first land battle of the War of 1812; the Americans tried to recapture it but failed, regaining control only by the passage of another treaty in 1815.

After that, German immigrant John Jacob Astor ran the Great Lakes fur trade, with increasing sophistication, until a European preference for hats made of Chinese silk ended the era in the 1840s.

Today, Fort Mackinac sprawls along the brow of a 100-foot bluff on Mackinac Island, high above Marquette Park.

© Beth Gauper

The tourist era started not along after the end of the fur-trade era, and soldiers posted on the isolated island spent most of their time building roads, cutting wood for buildings and steamships and leasing property for summer cottages.

"First they came for the fur, then the fish, then fun, and now fudge," said the interpreter manning the American Fur Company Store, one of five historic buildings at the foot of the bluff.

Inside the fort's walls, soldiers in Prussian-style spiked helmets interpret the 1880s, giving rifle-firing demonstrations and recruiting children to join their ranks in military drills.

During high season, there are re-enactments of a court martial, concerts of military music and tours of soldier life.

But for many tourists, the high point of a visit to Fort Mackinac is lunch on the veranda of the Tea Room, with its dreamy view of the park, marina and ferry traffic.

Other fur-trade sites are sprinkled all over the region: "If it was along a river, it was in the fur trade," says Patrick Schifferdecker, who interprets Francois Boucher and John Sayer at Minnesota's Snake River Fur Post.

© Beth Gauper

In the Twin Cities, Historic Fort Snelling had one foot in the fur trade in its early days. The Sibley House in Mendota is a fur-trade site; so is Traverse des Sioux in St. Peter.

In truth, nearly every historical site in the region has something to do with the fur trade. The Forks in downtown Winnipeg is a lode of fur-trade history, as is the Lower Fort Garry National Historic Site in nearby Selkirk.

In Green Bay, the first permanent European settlement in the Midwest, Heritage Hill State Historical Park preserves fur-trader cabins and a Jesuit chapel.

Madeline Island was a fur-trade center; in La Pointe, the Madeline Island Historical Museum has excellent exhibits on the fur trade.

The Mississippi river flats of Prairie du Chien were considered the hub of Upper Mississippi trade by three nations. It was the site of Wisconsin's only War of 1812 battle, re-enacted yearly on the grounds of Villa Louis, built with the fur-trade profits of Wisconsin's first millionaire.

In summer, fur-trade rendezvous and interpretive programs are in full swing. It's the kind of history people can really sink their teeth into.

Trip Tips: Fur-trade sites in the western Great Lakes

© Beth Gauper

At the sites below, costumed interpreters re-enact life in the fur trade.

Forts Folle Avoine near Danbury, Wis.: It's open Wednesday-Sunday from Memorial Day weekend through Labor Day weekend and for tours on Saturdays in September. Admission is $10, $6 for children 5-15. It's on County Road U, three miles west of Wisconsin 35 between Danbury and Webster.

Events include Yellow River Echoes in June, the Great Folle Avoine Fur Trade Rendezvous in July and the fall encampment, Dagwaagin Gabeshi, in October. 715-866-8890.

Grand Portage National Monument in Grand Portage, Minn.: The depot is open from Memorial Day weekend through mid-October; the rest of the year, only the visitors center is open.

Admission is free. Rendezvous Days and Powwow is on the second weekend of August. 218-387-2788.

For more, see Life on the Grand Portage.

© Beth Gauper

Colonial Michilimackinac in Mackinaw City, Mich.: It's open from early May to early October, but the daily schedule from mid-June to late August includes nonstop re-enactments and demonstrations. Admission is $14.50, $8.75 children 5-12, a little cheaper when bought online or as part of a combination ticket.

The big Fort Michilimackinac Pageant is over Memorial Day weekend, featuring 400 re-enactors.

For more, see Destination: Mackinaw City.

Fort Mackinac, Mackinac Island, Mich.: During the mid-June to late August high season, admission includes five other historic buildings staffed by interpreters. Admission is $15.50, $9.25 children 5-12, a little cheaper online. Call 231-436-4100.

For more, see Touring Mackinac Island.

Snake River Fur Post near Pine City, Minn.: It's open Thursday through Monday from Memorial Day through Labor Day weekends and for special events. Admission is $10, $8 for children 5-17, free for Minnesota Historical Society members. It's disabled-accessible.

Events include Open House (free admission) on the first Sunday in June; Children's Day in August; Festival of the Voyageur in September; and Mystery at the Fur Post in October. 320-629-6356.

Fort William Historical Park in Thunder Bay, Ont.: It's open year-round. In summer, admission is $14, $12 for children 13-17 and $10 children 6-12 (check at your hotel for discounts).

Events include Anishawbe Keeshigun in June and Haunted Fort Nights in October. 807-473-2344.

For more, see Exploring Thunder Bay.