Heritage travel: Switzerland

In Wisconsin's cheese country, townspeople hang on to tradition.

© Beth Gauper

In the Upper Midwest, the Swiss are insignificant — in numbers. Not many left the Old World. But the ones who did have had more success transplanting their traditions than nearly any other immigrant group.

In the southwest Wisconsin town of New Glarus, Germanic platitudes unfurl in Gothic script on the plaster of half-timbered chalets, over window boxes overflowing with geraniums. A little baker hangs over the doorway of the Bäckerei, where glass cases display almond-flavored brätzeli and anise springerle cookies.

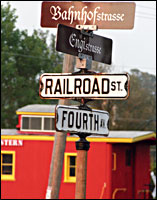

The sign over the town fire department reads "Feuerwehrhaus," and Railroad Street is Bahnhofstrasse.

In the 1840s, the Swiss canton of Glarus, southeast of Zurich, had been hit hard by the Industrial Revolution and recession, and it couldn't support all of its weavers and cloth printers. So it formed the Glarus Emigration Society and sent two trustees to buy land in the New World.

The first 131 immigrants were desperately poor when they arrived in 1845, and at first they suffered. They weren't farmers, but they liked the idea of owning land, and eventually they learned to grow wheat and raise dairy cattle.

For generations they flourished, and few of their children spoke English before they entered kindergarten. During World War I, anti-German sentiment made it harder to use their native dialect, but it wasn't until the 1930s that they noticed their culture fading.

There's nothing more Swiss than "Wilhelm Tell," the famous Schiller drama in which a 13th-century patriot defies an Austrian tyrant during the struggle for independence. So in 1938, the town of 2,000 started an annual festival that featured open-air performances of the play in German and English.

"They realized that if they didn't act then, a lot of the old ways and heirlooms would disappear, and they wouldn't be able to get them anymore," said Duane Freitag of Greendale, Wis., who grew up in New Glarus and has researched its history. "After World War II, they really got rolling."

Cheese and chalets

© Green County

One of the projects was the Swiss Historical Village, which started with one pioneer building in 1942 and grew into a collection of original buildings and replicas. Guides lead visitors around the exhibit hall and 13 small buildings, including a cheese factory.

During Oktoberfest, master cheesemakers come to make old-style cheese in its enormous copper vat, brought by oxen from Milwaukee in the late 1860s.

Then in 1962, after the local evaporated-milk plant closed, townspeople had to change tack again.

"Everybody went into a panic, but they didn't move," Freitag says. "A lot of people were able to get jobs in Madison, and they started paying a little more attention to tourism."

Alpine facades went up on the buildings downtown, along with Swiss canton flags. In 1965, townspeople added annual performances of a play based on the classic children's book "Heidi."

© Beth Gauper

The tourists came, and the town prospered again. Today, it's a favorite weekend getaway for tourists from Madison, Milwaukee and Chicago.

But it's not just an act put on for tourists. In New Glarus, people regularly eat Kalberwurst, a mild veal sausage, and Landjaeger, a jerkylike sausage.

They sing in the Männerchor, play the alphorn and practice Scherenschnitten and Fahnenschwingen, the traditional skills of scissor-cutting and flag-throwing.

As New Glarus becomes a bedroom community for Madison, a smaller proportion of its residents are of Swiss descent. But many newcomers become honorary Swiss, pitching in during town heritage events.

For more, see Swiss at heart.

Old World charm

Just to the south, Monroe, Wis., looks like classic Middle America, with its magnificent 1891 Romanesque courthouse rising over a shop-lined square. But it too is Swiss, populated by immigrants from Canton Bern.

It's the capital of cheese country, with co-ops and factories fanned out through the countryside, including North America's last Limburger plant and the mail-order firm Swiss Colony, founded there in 1926.

It has its own yodeling club, and traditional Swiss arts, such as Kerbschnitzen, still are taught at Monroe Arts Center.

At Baumgartner's tavern on the square, old-timers sit in the back room playing Jass, a betting game with cards. In the front room, locals and tourists alike buy bricks of well-aged cheese.

Two blocks away, they sit in the old Ratskeller in the basement of Turner Hall, eating cheese and onion pie and sipping Huber beer, made down the street.

© Beth Gauper

At the Historic Cheesemaking Center in the restored train depot, there's a shrine to cheesemaking, with shelves of old Swiss harps and the lids on which 200-pound wheels of Swiss cured.

In the old days, artisan cheese was made, sold and consumed within a few miles of the cows that gave the milk — and in Monroe, it still is.

Emigrants from Switzerland also settled in southeast Minnesota, in the village of Berne, and on the Wisconsin side of the Mississippi, in Alma and Fountain City. But they were surrounded by emigrants from Norway and other countries, and after a few generations, they blended in.

But in Green County, nearly everyone was Swiss, and it was easier to keep the heritage going. Today, even the non-Swiss are happy to claim it.

Go to a festival

New Glarus holds many Swiss heritage events throughout the year: the Heidi Folk Festival in June, Volksfest in August, Oktoberfest in September and a Christkindli Market in December.

On Labor Day weekend, there's a Wilhelm Tell Festival, an outdoor pageant with a Swiss fashion show and children's lantern parade.

Eat and drink

This is what you want to do in this part of Wisconsin, where Old World flavors still are favored over "lite" or low-fat anything. For more, see Cheese country.

In New Glarus, Wis., nearly all the restaurants serve such Swiss dishes as roesti, hash browns made with onion and aged cheese; raclette, melted cheese served with new potatoes; and pastetles, slices of veal, pork and chicken in a pastry shell with mushrooms in a wine-cream sauce.

The Glarner Stube is intimate and atmospheric, and the New Glarus Hotel has glassed-in balconies that make a great place for Sunday brunch.

Puempls, which has 1913 Napoleonic murals on its walls and dollar bills stuck to its ceiling, is a good place to sample New Glarus craft beer, made down the road at New Glarus Brewing Co.

New Glarus Bakery makes very good European and Swiss pastries, and the Maple Leaf sells Swiss chocolates.

In Monroe, Wis., Baumgartner's is famous for its cheese sandwiches, especially the Limburger sandwich, served on rye with raw onion. At Turner Hall, the Ratskeller serves classic Swiss fare.

© Torsten Muller

Both serve beer made a block away at Minhas Craft Brewery, formerly Joseph Huber Brewing Co., the second-oldest continuously operating brewery in the nation.

Visit a heritage site

In New Glarus, Wis., guides take visitors on tours of the Swiss Historical Village, telling stories about the community as they show a tiny pioneer cabin, a beekeeping house, a school, a blacksmith shop, a print shop and a cheese factory, among other buildings.

Two waist-high relief maps compare the steep peaks around Glarus with the gentle hills around New Glarus.

Also in New Glarus, the Chalet of the Golden Fleece is a replica of a Swiss Bernese mountain chalet, built in 1937 and filled with Swiss woodcarving, antiques and artwork. Tours are by appointment.

The Swiss Center of North America is based in New Glarus and serves as a clearinghouse for Swiss and Swiss-American heritage organizations, businesses, embassies and consulates.

It includes a genealogical research library.

In Monroe, Turner Hall displays interesting historic memorabilia and photos. It's two blocks south of the square at 1217 17th. Ave.

The Historic Cheesemaking Center, also the visitors center, is open daily from March to November and Thursdays-Saturdays from December to February.

For more, see Wisconsin's cheese country.