Life on the Grand Portage

Once, a corner of northeast Minnesota was the center of the fur-trade universe.

© Beth Gauper

Long before Minnesota existed, Grand Portage was as familiar a name to many Europeans as George Washington.

As the American Revolution drew to a close in the East, traders at this Lake Superior outpost were busy minting the interior's first millionaires.

It was the crossroads of a continent, the place where voyageurs laden with goods from Montreal met voyageurs laden with beaver pelts from the Canadian wilderness.

Then, it was time for Rendezvous, where the French-Canadian paddlers cut loose while their Scottish bosses traded — making money hand over fist for shareholders of the North West Co., one of the first modern corporations.

"It was making a profit of $1.7 million in our money today," said Grand Portage National Monument ranger Steve Veit. "It was the first business operated on an intercontinental basis."

Its product was the lowly beaver, whose barbed fur could be turned into the felt top hats coveted by Europe's high society.

The pelts were called "soft gold," and North West collected them using such practices as centralized management, branch offices, customer assurance, market surveys and mergers.

In 1793, its best year, 182,000 pelts came through Grand Portage.

"In its heyday, people on the streets of London knew where Grand Portage was," said Pam Neil, chief of interpretation. "It was that important."

Today, no one wears top hats or owns stock in the fur trade, so Neil has to explain.

"When I say it's like Microsoft, people automatically understand that," she said. "And there were 120 posts between here and modern-day British Columbia, so if I say it's like Wal-Mart, they get it every time. That's the level these guys were operating on."

Work horses of the fur trade

For the voyageurs who actually did the work, the wilderness was one big sweatshop. They worked 12 to 14 hours a day, subsisting on dried corn, pemmican, peas, grease and salt pork.

The mangeurs du lard, or pork eaters, paddled up to 5 tons of goods and men through the Great Lakes to and from Montreal, across 36 portages. The hivernants, who wintered in the interior, had 36 portages just to get to Rainy Lake.

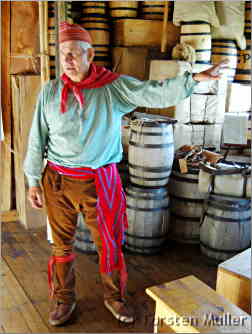

© Torsten Muller

But all the portages paled in comparison with the 8½-mile Grand Portage, a detour around the cataracts and chasms on the lower 22 miles of the Pigeon River.

Each voyageur had to haul eight 90-pound packs; carrying two at a time, the men needed seven days and 70 miles of walking to complete it.

This Kitchi Onigaming, or great carrying place, was the critical link between the Great Lakes and a virtually unbroken water highway to the west. But it was a miserable gantlet of muck and mosquitoes, rising nearly 700 feet to the Pigeon River.

When the first European to use the route, Pierre de la Verendrye, arrived in 1731, his men "mutinied and loudly demanded that I should turn back."

Over the years, in such books as Grace Lee Nute's "The Voyageur," these workhorses of the fur trade have been portrayed as jolly, carefree fellows who belted out saucy tunes to relieve the tedium and competed to see who could paddle fastest or carry the heaviest pack.

But ranger Veit doubts they were quite so lighthearted.

"I think that's a Grace Lee Nute spin on things," he said. "I don't think it was all that jolly. It was the best a lot of these young guys could do."

They were mostly illiterate second and third sons from hardscrabble farms along the St. Lawrence Seaway, he said, whose families were paid in cash when they signed with the fur companies.

Many later fell into deep debt to the company by buying overpriced goods at its Grand Portage store, making themselves, in effect, indentured servants.

They often died young of back injuries and hernias, but they didn't see themselves as victims.

"They knew what to expect," said volunteer interpreter Jim Alling of Bloomington, Ind. "Their expectation was, 'I'm going to knock my brains out being a voyageur.' There was a pride in being able to endure."

Moving across the border

Since the Scottish-owned depot lay on American soil, it was moved lock, stock and barrel in 1803 to the banks of the Kaministiquia River in Thunder Bay, Ontario, from which paddlers could reach Rainy Lake on a longer route. Soon, the site was overgrown.

© Torsten Muller

But in the 1930s, with the help of federal work programs, the Grand Portage site was excavated and the stockade reconstructed by crews of local Ojibwe, many of them descendants of voyageurs.

The band donated the land, and it became a national monument in 1958; after the first re-creation burned in 1969, a more elaborate one was built, with a palisade, Great Hall, lookout tower, kitchen, warehouse, fur press and Ojibwe encampment.

Now, a heritage center first promised in 1958 is open, enabling the park service to display the artifacts found over the years and to better tell the story of the Ojibwe, who made the fur trade possible and whose land surrounds the monument.

There are a thousand stories, and every day, a corps of costumed interpreters tells some of them.

When I was there on opening weekend, Veit was in the brown wool suit of a clerk, standing in front of a map of Scottish fur trader Alexander Mackenzie's successful trek across the continent in pursuit of the fabled Northwest Passage.

"We're all fans of Mackenzie because he got to the Pacific first," he said. "Mackenzie made it in 1793, 10 years before the guys with better PR and Thomas Jefferson backing them. He made a blueprint for Lewis and Clark to follow, in terms of saying it could be done."

In the Ojibwe encampment, Bemidji State student Jeremy Kingsbury, in the red sash and muslin blouse of a voyageur, was starting his fourth summer at Grand Portage, selecting logs for a garden shelter.

"The most important thing I say is that it wasn't only negative, what happened between the Ojibwe and the Europeans," he said. "They didn't drop what they were doing to participate in what the Europeans were doing, and they didn't go away just because the Europeans showed up. And they're still not away."

Kingsbury isn't Ojibwe, though he has studied the language and culture since he was in high school.

"We've gone through our fair share of native interpreters," he said. "After a while, they can't handle it anymore. They get it only two or three times a year, but it's, 'Hey, it's Pocahontas.'"

In the heirloom garden, volunteer interpreter Sue Alling was working with a rake made of deer antlers.

"The Ojibwe called this a three sisters garden — squash, bean and corn," she said. "The corn grows up, the pole beans grow up around the cornstalks and the squash leaves cover the ground from the baking sun," she said.

In the warehouse, Jim Alling showed us a North West Co. invoice from April 27, 1797, listing the precise contents of one 36-foot-long Montreal canoe: 8,100 pounds, including 5,400 pounds of cargo and 2,700 pounds of men, paddles, tools, rum and beef.

© Beth Gauper

"They were fanatics about record-keeping," he said. "They used them for forecasting the future, to know what to order — if the Cree wanted wool blankets, for example, you had to get them from London."

It wasn't a cooking day in the kitchen, where the descendants of the original Ojibwe fishermen bring in herring twice a week for interpreters to cook, along with bread and such seasonal dishes as rhubarb pie.

Instead, interpreter Karl Koster showed us a bowl of pemmican, a mixture of suet and buffalo meat that's pounded and dried for easy transport.

It was so important, he said, there were "pemmican wars" between North West Co. and its chief rival, the Hudson Bay Company.

"It was the Power Bar of the 18th century," he said. "You needed something that could fuel you up if you could not stop and hunt."

On a typical day at Grand Portage National Monument, said Neil, visitors can watch historic weapons being fired, hear a bagpiper, try on the clothing of the fur trade, play voyageur games and see a canoe being built.

© Beth Gauper

"We always have somebody doing something," she said. "It's a very interactive site. You're not going to find a ranger with his face stuck in a book."

The biggest event of the year is in mid-August, when the national monument holds a rendezvous and the Ojibwe band holds a powwow.

A modern-day equivalent of the 18th-century rendezvous, which could draw as many as 1,200 people over a month, it's a colorful juncture of cultures, with re-enactors mingling with Ojibwe, Cree and Assiniboine dancers and the many people who are enthralled by the fur-trade era.

"It's a pretty amazing story," Neil said. "In fact, I think Mel Gibson should do a movie about it. We're a little unit with a very big story to tell."

Trip Tips: Visiting Grand Portage, Minnesota

Getting there: It's 5½ hours from the Twin Cities, 35 miles north of Grand Marais.

Events: August, Grand Portage Rendezvous and Powwow (plan ahead; lodgings book up a year in advance).

Grand Portage National Monument: The historic fur-trade depot and Heritage Center are open daily from the Saturday of Memorial Day Weekend through Columbus Day in October. Admission is free.

The rest of the year, the Heritage Center is open Monday through Friday and Saturdays in December. Visitors can borrow snowshoes for use on trails.

A replica of the post's replacement, Fort William, is 45 miles north in the huge Fort William Historical Park in Thunder Bay. It's well worth a visit.

For more, see Exploring Thunder Bay.

© Beth Gauper

Hiking: The one-mile round-trip Mount Rose trail, which has 16 interpretive posts, is open dawn to dusk. It's asphalt but very steep, and provides good views of the stockade and bay.

The steep, two-mile round-trip Mount Josephine trail provides an even wider panorama; it starts from a small parking area off County Road 17, 1½ miles east of the monument.

The Grand Portage trail is open year-round; there are two large primitive campsites at the other end, on the site of old Fort Charlotte.

Grand Portage State Park: Along the Pigeon River on the international border, this park contains Minnesota's highest waterfall, the spectacular 120-foot High Falls. The half-mile trail to it is disabled-accessible.

A more challenging four-mile trail leads to Middle Falls, with magnificent views from the ridge that splits the park. 218-475-2360.

Accommodations: Grand Portage Lodge & Casino is on the lakeshore and has 100 rooms. It also has a pool and restaurant.

The marina has an RV Park with full hook-ups and tent sites. The tent sites are a great option during Rendezvous, when the entire area is booked up.

The lodge also has a staff naturalist who leads van trips to the Spirit Little Cedar Tree, a twisted, 400- to 500-year-old cedar at the tip of Hat Point that is sacred to the Ojibwe. Trips to the tree, to which access is restricted, are given on weekends.

Hollow Rock Resort on Hollow Rock Bay, three miles south of Grand Portage, has five cabins. It's now owned by the Grand Portage Lodge & Casino.

Grand Marais, 35 miles south, has many motels, B&Bs and a municipal campground.

Visiting Isle Royale: From the Grand Portage marina, the Voyageur II travels to two harbors of the beautiful national park, Windigo on the western side of the island and Rock Harbor on the north. The Wenonah also makes a trip to Windigo.

Note: Isle Royale is part of Michigan, so it's on Eastern time, an hour ahead.

Reservations are required and should be made as soon as possible. 888-746-2305, GPIR Transportation Line.

For an overview of Isle Royale National Park, see Isle Royale reverie.

Background: Carolyn Gilman's "The Grand Portage Story" (Minnesota Historical Society Press) is a wonderfully readable history of the site.