Valleys of Vernon County

In the nooks of Wisconsin's coulee country, people of all kinds found a niche.

© Beth Gauper

In 1862, a poor Norwegian couple and their four small children, including their infant son Thorvald, joined a wave of immigrants to Wisconsin, eventually settling in the coulees of Vernon County.

Vernon County was an interesting place in the 1860s. Only a generation before, Black Hawk and his band had fled through it, hounded by militia.

The band ran headlong into a slaughter that remains one of the most shameful chapters in U.S. history. Today, 11 plaques mark the route, which ended near the town of Victory.

Norwegians poured into the steep, flat-floored valleys that reminded them of home. Italians fished along the Mississippi from a town they called Genoa.

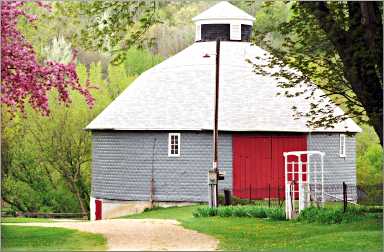

Free blacks already had arrived and were joined by newly freed slaves. One of them had a son who became an expert builder of round barns, of which Vernon County has the nation's highest concentration.

In 1966, Old Order Amish began arriving from Ohio, settling onto the high ridges and tilling the land with horse-drawn plows. Like the hard-working settlers before them, they thrived.

The land, while beautiful, is difficult. Glaciers slid around it rather than over it, leaving a jumble of little valleys boxed in by pointy hills.

Norwegians and former slaves

The valleys weren't as rocky as the ones in Norway, however, and usually a creek wound through their flat floors. This made the Norwegians optimistic.

In 1865, my great-great-grandfather Rolf Olson Gauper of Chaseburg wrote home to his father, Ole Trondsson Gauper.

"When I consider my children, I think that their futures will be very good, yes, much better than if I had stayed in Norway," he wrote. "Here, the common laborer and the poor are not so shamefully treated as they are in Norway . . . Poverty is considered to be honest, and that poor man will they eagerly help and support."

Black farmers found the same thing to be true on the east end of Vernon County, among the Bohemians, Irish and Norwegians in Cheyenne Valley. They were the largest community of rural blacks in Wisconsin, and old photos show their complete integration into society.

One of their descendants, Gen Reko, attributed it to the practicalities of life in an isolated valley.

"One person didn't have more than the other, and if they did, they shared," said Reko, who stayed in Cheyenne Valley. "They all went to school and church together, and as a whole, everybody got along fine."

Reko descended from Mycajah Revels, who was of Cherokee, African and English ancestry and arrived in Vernon County in 1854.

© Beth Gauper

She was raised by her grandmother, Flora Shivers, and Flora's husband Alga, a college-educated son of a former slave who built round barns, spoke Czech and French and was one of the area's most popular residents.

One year, Reko helped organize a reunion that drew 250 descendants to Hillsboro. "People had lots of stories to tell about Algie," she said.

Surprises everywhere

Alga Shivers' round barns are among seven on a Cheyenne Valley heritage tour mapped out for tourists.

Other driving tours include all 12 of the county's remaining round barns and the route taken by Black Hawk and his band in 1832. And there are tours for people who want to visit Amish farms and for bicyclists looking for scenic routes.

Exploring is the thing to do in Vernon County. On a topographic map, coulees are represented by tight little squiggles; equally squiggly county roads follow creeks and rise to ridges that have spectacular views.

From the towns of Romance to Avalanche, from Norwegian Hollow to Irish Ridge, there's something surprising around every turn — a round barn, a throng of wild turkeys, an Amish farmer bouncing on his plow.

Even before I knew that my great-grandfather Thorvald grew up in Vernon County, I loved it.

One spring, I hunted morels and went for a bird walk in the Kickapoo Valley Reserve. In summer, I canoed the crooked Kickapoo River, paddling in all four directions of the compass on just the six miles south of Ontario.

Near Westby, I visited the open-air Norskedalen heritage museum and froze my toes watching an international ski-jumping competition on a 40-story jump lovingly maintained by local Norwegians.

One fall, I followed the route of Black Hawk's retreat. Another fall, I took a guided tour of Amish farms along the county's northern border, around Cashton.

Tracing ancestors

I headed to Vernon County again one May, as flowering trees were infusing the green hills with pink. Driving up Hamburg Ridge, I passed the first of many bicyclists; local racers have discovered that these punishing hills are a good place to train.

In Chaseburg, I stopped at Fortress Bank to ask for directions to Bad Axe Lutheran Church, and manager Janet Stafslien sent me down to Purdy, on the Bad Axe River.

"It's really pretty down there," she said. "People like to fish, and now people from the cities are building houses down there."

People from La Crosse? "No, Chicago," Stafslien said. "That's what we get around here."

The city folk are driving up land prices and taxes, a hardship for the Amish, who are determined to buy farms near each other.

© Beth Gauper

I hadn't known they'd settled this far west. Up the hill from Chaseburg, I stopped to buy a blueberry pie at the Miller farm, whose matriarch said they'd moved there in 1996.

Most of the Gaupers had died or left Vernon County by the 1930s. My great-grandfather Thorvald was first to go, changing his name to Thomas and decamping for Eau Claire before he was 18, apparently with his older brother Lars, who became Lewis.

Their brothers Ole and Emil, however, are buried at Bad Axe Lutheran Church, near the coulee where Ole's sorghum mill was washed away by a flood.

From Purdy, I followed Norwegian Hollow into Viroqua, which occupies the only flat stretch of Vernon County. It's the county's only outpost of coffeehouse-and-gallery culture, as well as the home of both its stoplights.

On the east side of town, past the big, red-brick buildings of the Viroqua Leaf Tobacco Co. — the Norwegians were skilled cultivators — I found the red-tiled Cina barn.

Round barns were easy to build, efficient and wind-resistant, but they fell out of favor when square hay bales and pipeline milking systems were introduced.

From there, I headed for a farm guesthouse to meet my children and nieces, who had driven over to join me. They'd already seen lots of Amish buggies clip-clopping over county roads and were fascinated by their no-frills lifestyle.

"I feel so sorry for those Amish boys," my son Peter said. "No TV, no computer, nothing."

Visiting the Amish

The next day we drove down to Ontario and two miles west to Der Bake Oven, on an Amish farmyard where two small children in blue and black clothes were swinging on a rope. They waved at us, but they were too shy to return our hellos.

© Beth Gauper

Then, with the freshly made doughnuts, raspberry rolls and bags of cashew crunch that we bought, we drove up to Wildcat Mountain State Park.

The Old Settlers Trail was only 2½ miles, but it took us past nearly every feature of a coulee landscape.

From an overlook with a sweeping view of Ontario, we climbed onto a cavity-riddled outcropping of gold sandstone and down the valley on a path lined with trilliums and spring beauties.

A creek gurgled along on the valley floor, past clumps of marsh marigolds. We walked through a corridor of red pines and ascended again, stopping to take in another view just short of the end.

From the park, we took a glorious roller-coaster ride on County Road P to the blue Evanstad barn near Dell, then north on D to sample squeaky cheese curd at Old Country Cheese and back to Wisconsin 33 between Cashton and Ontario, which is lined with Amish farms.

We stopped at one for more cashew crunch, but instead found a friendly Amish man named David, trying to calm a colt he'd just bought.

The colt's parents, he told us, were racehorses. The Amish like to use retired racehorses to pull their buggies because they're used to loud noises, such as those made by passing cars.

David invited us to look at the back of the barn, where a newborn colt wobbled next to its blind mother, then took us to the basement and brought out three wiggling Chihuahua-Jack Russell terrier puppies for us to hold. He sells them as pets, he said.

The puppies made Peter's day.

"All the Amish men we've run into have been jolly," he noted.

Heading home, we stopped at another farm, where an Amish girl in a green shirt sold us plants. We found Pine Grove bakery on another farm and bought maple syrup, jam, cookies and a mixed-berry pie with heart-shaped cutouts; the hard-working baker noted ruefully she had only two daughters to help her.

"What a cool day," said my niece Alissa, when we got back. "I feel as if I'm in a different country — different landscape, different people."

The next day, they rode bikes on the Elroy-Sparta State Trail and I drove to two round barns near Mount Tabor, in the heart of the black settlement, and to Cheyenne Settlers Heritage Park in Hillsboro.

© Beth Gauper

Syttende Mai in Westby

Then we all drove on to the Norwegian stronghold of Westby for the annual Syttende Mai parade, celebrating Norwegian constitution day.

The Westby area was known as "America's little Gudbrandsdal," after the valley from which many immigrants came, including Rolf and Riah Gauper, and it's still thoroughly Norwegian.

Visiting Norwegians, says gift-store owner Jana Dregne, often say the locals are more Norwegian than they are.

"We don't have industry," she jokes. "We have heritage."

Trip Tips: Vernon County in southwest Wisconsin

Getting there: Westby is half an hour southeast of La Crosse.

Annual events: First weekend of February, Snowflake Ski-Jumping Tournament in Westby. Weekend closest to May 17, Syttende Mai in Westby. Mid-June, Midsummer Fest at Norskedalen. Mid-July, Driftless Music Festival in Viroqua. Mid-August, Larryfest folk-music festival near La Farge. Second weekend of October, Civil War Experience at Norskedalen, with battle skirmishes (for more, see Civil War, up close).

Accommodations: On Viroqua's Main Street, the newly restored 1899 Hotel Fortney has 14 rooms.

In Westby, Westby House Victorian Inn has five rooms and two suites in a guesthouse.

On a ridge outside La Farge, Trillium has two cottages.

There also are many country cabins and cottages for rent, including the Paulsen Cabin at Norskedalen.

© Beth Gauper

Camping: Vernon County has lovely county parks, including Esofea/Rentz Memorial Park on the North Fork of the Bad Axe River, nine miles northwest of Viroqua, and Sidie Hollow Park, on a lake three miles west of Viroqua.

Wildcat Mountain State Park has 30 sites, all reservable, with flush toilets and showers. It also has 26 miles of trails. 608-337-4775.

Dining: In Viroqua, the Driftless Cafe offers small plates and uses produce and meats from nearby organic farms, and the Food Co-op has an excellent deli.

Round barns: The Vernon County Historical Museum sells "Round Barns of Vernon County."

It also supplies a map of 11 markers along the route of Black Hawk's retreat.

For more, see Road trip: Black Hawk's trail.

Cheyenne Valley heritage tour: For the route map, call Hillsboro, 608-489-2521.

Amish businesses: Many Amish businesses around Cashton sell furniture, candies, plants, produce and home goods. They welcome visitors, except on Sunday.

Visitors also can stop if they see one of the hand-lettered signs that tell which farms do business.

Norskedalen: The nature and heritage center, three miles north of Coon Valley off County Road P, is open daily in summer and offers classes in Scandinavian folk arts.

Bicycling: The 5.5-mile, paved Viroqua-Westby Trail links Viroqua and Westby. Bluedog Cycles in Viroqua rents bikes.

The Elroy-Sparta State Trail skirts the east edge of Vernon County. For more, see Cycling in coulee country.