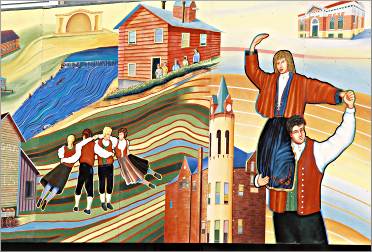

Norwegians among us

Long after the first immigrants arrived, descendants' love of the culture stays strong.

© Torsten Muller

Across the Upper Midwest, an unusually large number of people know that bunad is not a crude anatomical term and that krumkake is something sweet from a bakery.

More than perhaps any other European immigrants, Norwegian-Americans have carried on old-country traditions, even those that folks back in Norway largely have dropped (see: lutefisk-eating).

They're on full display in May, when Norwegians celebrate the anniversary of the signing of a democratic constitution on May 17, or Syttende Mai.

From the Chicago suburb of Park Ridge to Stoughton and Westby in Wisconsin, Spring Grove in Minnesota and the Red River Valley, Norwegian-Americans will be fiddling, folk-dancing and troll-hunting.

Today, even Norwegians from Norway marvel at the extent to which Norwegian-Americans have preserved the culture they left.

Many women own bunads, the dresses whose colors and embroidery identify the region from which their ancestors came.

They make krumkake, a delicate cone-shaped cookie, and bake scalloped sandbakkels, both made with lots of butter. They practice rosemaling, painting floral designs on wood, and carve wood in intricate acanthus leaf patterns.

Some play the eight-stringed Hardanger fiddle, whose haunting notes sound like homesickness.

Though most immigrants were desperately poor, they hated to leave Norway — so when they got here, they created lots of little Norways.

Why they left

In the 19th century, Norway was a bad place to be a peasant.

© Beth Gauper

Its population was increasing, mostly squeezed onto the slivers of land that could be cultivated — only 3 percent of the country.

Farm mechanization pushed out landless laborers, and a rigid social hierarchy gave them no chance to improve their lot.

So, they left. Starting in the late 1830s, Norwegians came to southeastern Wisconsin, forming enclaves that drew new immigrants.

The farmers stayed for a while before skipping to newer Norwegian settlements in the coulee country of southwest Wisconsin, the bluff country of southeast Minnesota and Iowa and then the fertile Red River Valley of Minnesota and North Dakota.

Norwegians who fished headed for the rocky shorelines of Door County and Minnesota's North Shore.

By 1915, Norway had lost 750,000 people to the United States, contributing, after Ireland, the highest percentage of its population to the new country.

Hanging onto tradition

But they didn't forget their homeland.

Each Christmas, Norwegian-Americans march into the nearest Norsk deli to buy lutefisk, the lye-soaked dried cod that once was a staple for peasants in Norway.

They grate potatoes for lefse, the flat peasant bread, and roll thin butter cookies on krumkake irons.

They send their children to Norwegian camp, read them books about mischievous trolls and dress them up in woolen Dale sweaters.

They put up troll and Viking statues in public spaces from Mount Horeb, Wis., to Spring Grove, Minn., where bottles of the local Spring Grove Soda bear the slogan "Mange Tusen Takk," Norwegian for "Thanks a million."

Norwegians, it seems, are the most sentimental of immigrants, and they often chose land that reminded them of home.

© Beth Gauper

Humorist Garrison Keillor writes, "Our ancestors chose this place, tired from their long journey, sad for having left the motherland behind, and this place reminded them of there, so they settled here, forgetting that they had left there because the land wasn't so good.

"So the new life turned out to be a lot like the old, except the winters are worse."

Festivals

Syttende Mai (pronounced SEH-tend-ah MY) is celebrated on the weekend closest to May 17 in Stoughton, Westby and Woodville in Wisconsin; Spring Grove and Milan in Minnesota; and Park Ridge in Illinois.

In Decorah, Iowa, it's always celebrated May 17 with a traditional children's parade.

Syttende Mai in Stoughton is the biggest in the nation and almost certainly bigger than any in Norway, though its organizers don't want to brag.

For details, see Celebrating Syttende Mai.

Midsummer Fest is in mid-June at Norskedalen open-air heritage museum near Westby.

The Midwest Viking Festival is in June in Moorhead, Minn., sponsored by five Scandinavian societies.

The big Nordic Fest in Decorah, Iowa, is the last weekend of July. Plan ahead. For details, see see Nordic nirvana.

Norwegian Christmas Celebration is the first Saturday in December at Vesterheim in Decorah, Iowa.

The Snowflake Ski-Jumping Tournament in Westby, Wis., is the first weekend of February. Local Norwegians carefully groom a 40-story ski jump, on which jumpers from all over the world compete.

For more, see A jumpin' joint.

Language and culture

© Beth Gauper

Sons of Norway, founded in 1895 in Minneapolis, is an international society that promotes Norwegian language, culture and traditions.

Concordia Language Villages in Bemidji, Minn., hosts Norwegian-immersion summer camps for youth and also programs for adults and families. Skogfjorden, the Norwegian village, began in 1969 with help from Sons of Norway and was the first permanent site.

For more, see Language camp for adults and Going abroad in Bemidji.

The Norwegian American Genealogical Center and Naeseth Library in Madison helps Norwegian-Americans research their family histories.

Mindekirken Norwegian Memorial Lutheran Church in Minneapolis holds weekly services in Norwegian as well as English and offers Norwegian language and culture classes.

Heritage sites

© Beth Gauper

Vesterheim in Decorah, Iowa. It's a village in itself, with 16 historic buildings, a four-level museum and a crafts and education center, where instructors teach rosemaling, acanthus carving, weaving and other folk skills.

It has its own church, its own stone mill and blacksmith shop and its own celebrations.

Its museum exhibits are open Tuesday-Sunday through April; from May through October, daily tours include the outbuildings.

For more, see A pocket of Norway.

Norskedalen Nature and Heritage Center near Westby, Wis. It includes the Bekkum Homestead, a collection of 13 buildings from nearby Norwegian pioneer farms, moved and reconstructed, and the Skumsrud Heritage Farm, with 11 reconstructed buildings, including an 1853 log house.

Norskedalen offers workshops and lectures all year at its visitors center, and in summer and fall, its schedule includes Norwegian-heritage events as well as such pioneer festivals as threshing bees and ice-cream socials.

Hjemkomst Center in Moorhead, Minn. It shows the re-created Hjemkomst (Norwegian for "homecoming") Viking ship and a replica of a medieval Norwegian stave church, and it also offers tours, lectures and exhibits.

© Beth Gauper

Old World Wisconsin near Eagle, Wis. Two Norwegian farmsteads and a school were moved to this sprawling site just southwest of Milwaukee, the nation's largest outdoor museum of rural life.

In the summer, interpreters take visitors back to the years 1845, 1865 and 1906, explaining how immigrants observed Old World traditions and adopted new ones.

Replicas of stavkirkes. The wooden churches that melded early Christianity with leftover paganism, are sprinkled all over the countryside.

Wisconsin's Door County has two, on Washington Island and on the grounds of Bjorklünden just south of Baileys Harbor, an estate owned by Lawrence University.

They're also found on the grounds of the Hjemkomst Center in Moorhead; on the grounds of Skogfjorden, Concordia University's Norwegian village north of Bemidji; and at Green Lake Bible Camp in Spicer, Minn.

Trolls in Mount Horeb, Wis. This town just west of Madison calls itself the Troll Capital of the World, and more than 15 carved wood trolls line its Main Street.

Its medieval-style wooden stave church has gone back to Orkdal, Norway, whose residents built it for the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Books

"Norwegians in Minnesota," by Jon Gjerde and Carlton C. Qualey (Minnesota Historical Society Press).

"Norwegians in Wisconsin," by Richard J. Fapso (Wisconsin Historical Society).