Heritage travel: Dakota and Ojibwe

Despite centuries of disruption, their cultures survive.

© Beth Gauper

In the 17th century, when Europeans began to flee religious and economic oppression, the New World was not an untouched wilderness.

In the wooded forests beyond Lake Superior, the Dakota and Ojibwe tapped maple trees for sugar, harvested wild rice and hunted the abundant game.

Many of them cultivated crops and lived in villages, like the Europeans. They were careful stewards of the land, reseeding rice beds and maintaining healthy soil through controlled burns, just as state agencies do today.

For the Dakota and Ojibwe, this already was the land of the free.

(For differences between the tribes, see Ojibwe or Chippewa, Dakota or Sioux? )

In daily life, they were deeply spiritual, perceiving the divine wherever they looked — in a thunderbolt from the sky, the swoop of an eagle, the twisted branches of an old cedar tree.

They raised children in extended family clans, imparting moral and ethical values with subtly nuanced stories and teaching by example. Leaders were appointed by group consensus, not to exert long-term control but to deal with specific challenges as they arose.

It wasn't the European way, but the French generally respected it when they arrived. Offering firearms, metal implements and woven blankets in return for furs, the French made life easier, but also started a dangerous dependence on trade goods.

By the time the furs ran out, the French were gone, replaced by hard-nosed Yankees who wanted something more than furs. The Dakota and Ojibwe had little to trade but land, and eventually, the Yankees got nearly all of it.

Without land, the Dakota and Ojibwe had no means of sustaining themselves or their culture. The tribes were set adrift in a sea of foreigners.

© Beth Gauper

Assimilation vs. tradition

Unlike the newly arrived Germans, Norwegians and Swedes, who set up ethnic enclaves where they could carry on their traditions, the Indians were expected to fade away into the general population.

Government agents urged them to cut their hair, wear suits and live in single-family houses. Missionaries urged them to swap their Creator for a different one, worshiping not in the natural world but inside a building.

Starting in the 1870s, Dakota and Ojibwe children were forced to attend boarding schools, where they were punished for speaking their own language.

By the time the schools finally closed, some as late as the 1960s, the language and stories — encoded with knowledge handed down from generation to generation — nearly were lost.

In the 1950s, the U.S. government stepped up the assimilation process, targeting relatively successful bands, such as the Menominee in Wisconsin, for termination. On the reservation, government officials gave young people bus money to relocate to faraway cities.

Ironically, white tourists helped preserve many of the old traditions. The Indian Allotment Act of 1887 fragmented reservations, and much of the land taken from the Indians was sold to white people for lake cabins and resorts.

When the vacationers arrived in the summer, Indian families set up roadside stands to sell them sweetgrass baskets, beaded moccasins and other traditional handicrafts. To entertain them, tribal members put on their regalia and performed in weekly powwows and dance ceremonials.

It was part of a hand-to-mouth existence for many until the advent of Indian gaming in the 1980s.

Still, their right to continue a traditional lifestyle continues to be challenged. In 1999, however, the U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed their right to hunt, fish and gather according to the Treaty of 1837, under which the Dakota and Ojibwe lost most of their land east of the Mississippi.

"People are still stunned that the treaty held up," says Charlotte Hockings of the Lac du Flambeau community in northern Wisconsin, site of violent protests against spear-fishing in the 1980s.

© Torsten Muller

In Wisconsin, the Dakota and Ojibwe are joined by the Potawatomi and Menominee; the Ho-Chunk, who once were called Winnebago; and two tribes from the east, the Stockbridge Mohicans and the Oneida, once part of the League of Iroquois.

Today, only 1 percent of the population of Minnesota and Wisconsin call themselves Indians, and many non-Indians know little about them.

Some people, says Hockings, still think Indians are savages. Others, who think fraud ended with the treaties long ago, think Indians should get on with their lives.

Well, they're trying.

Carrying on the culture

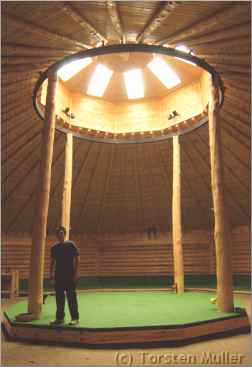

For many years, Hockings and her late husband, Nick, shared their culture at Waswagoning, an open-air site in northern Wisconsin that guided visitors through a typical year in the life of an Ojibwe band.

There was a maple-sugaring site, with a birchbark kettle hanging over a fire. There was a summer wigwam and a field for lacrosse, where boys learned battle skills, and doubleball, which taught girls the dexterity needed for harvesting wild rice.

In the forest, there was an arrow-maker's lodge, filled with the utensils used before white traders introduced metal.

For many of the visitors, who knew only what they saw in Hollywood movies, it was a revelation.

In Minnesota, the Four Seasons room at the Mille Lacs Indian Museum also shows sugaring, fishing and ricing camps, and guides tell about Ojibwe innovations, from early wildlife conservation to the first disposable diapers.

Videos show powwow dancers, and a computer translates English words into the soft, cushioned syllables of Ojibwe. In special programs, Ojibwe elders tell stories and teach classes in beading, weaving and other traditional crafts.

Nearby, Mille Lacs Kathio State Park holds traces of a palisaded village, one of 19 prehistoric sites built by the ancestors of the Mdewakanton Dakota, the "people who live by the water of the Great Spirit."

Once, the Dakota lived on the shores of Mille Lacs; according to Ojibwe oral tradition, they were forced out between 1745 and 1750.

Not far away, at the Snake River Fur Post in Pine City, Minn., and Forts Folle Avoine near Danbury, Wis., interpreters tell of the Ojibwe who worked in the fur trade.

Ojibwe life also is represented at Grand Portage National Monument and in Thunder Bay, Ontario, at Fort William Historical Park. Both re-created fur posts hold traditional powwows in summer.

In Canada, the first nations guard their heritage at such sites as Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Historical Centre, an Ojibwe village on the Rainy River where visitors can hear traditional stories, take classes and stay in tepees.

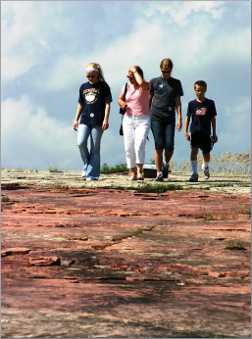

In southwestern Minnesota, members of prairie tribes still quarry sacred stone at Pipestone National Monument.

© Beth Gauper

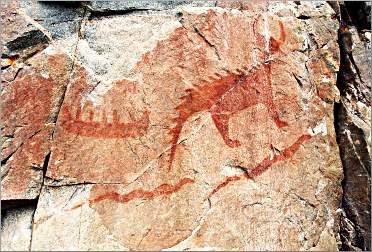

Nearby, at Jeffers Petroglyphs, their ancestors left an ancient story on a 1,000-foot-long outcropping of hard red quartzite that once was a place for prayer. In the interpretive center, members of prairie tribes often come to tell stories, dance and present programs about their culture.

And every weekend there's a powwow somewhere, giving non-Indians a unique portal into the Indian world.

But since there is no one "Indian" world, it's hard to grasp everything.

In the end, there is perhaps only one thing we really need to know. In Lakota, Mitakuye oyasin. In Ojibwe, Gakina awiya gidinawendimin.

In English, that means we are all related.

Go to a powwow or wacipi

This is when band members gather to greet old friends, replenish their sense of cultural identity and show off achievements. Traditional powwows are more like family reunions; at competition powwows, cash prizes are awarded.

At both kinds, the dancing and drumming celebrate each man and woman's artistry, spirituality and connection to ancestors and community.

The centerpiece is the Grand Entry; most are 1 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays and 7 p.m. Saturdays, but call in advance to find out for sure.

© Beth Gauper

Guests may want to bring tobacco to honor favorite dancers, drummers, or elders with whom they wish to talk.

Never enter the circle unless invited, and don't take photos when the announcer forbids them. Refer to outfits or regalia, not "costumes." Guests should stand during the Grand Entry and honor songs.

One of the first things visitors will notice is the many ways in which veterans are honored. Despite their history with the U.S. government, Indians take great pride in serving their country, and their young people have a long record of valiant service.

For a listing of Upper Midwest powwows and wacipi, see Powwow primer.

In Lac du Flambeau in northern Wisconsin, weekly powwows have been presented at the Indian Bowl since 1951.

For more, see Carrying the torch.

© Beth Gauper

Visit heritage villages

Just west of International Falls and over the border, on the Rainy River near Emo, Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Historical Centre is a Canadian National Historical Site.

Visitors can stay in a tepee, take handiwork classes, hear elders tell stories and take a boat trip to see pictographs. The visitors center includes an aquarium, exhibits and a restaurant that serves Ojibwe food.

For more, see Place of the Long Rapids.

Study the culture

In Lac du Flambeau in northern Wisconsin, the George W. Brown Jr. Museum and Cultural Center includes a four-seasons diorama, a rare 18th-century dugout canoe and a 7-foot, 195-pound sturgeon speared in nearby Pokegama Lake.

It offers Ojibwe culture programs and craft classes year-round.

On the west shore of Mille Lacs in central Minnesota, Mille Lacs Indian Museum includes engaging exhibits on Ojibwe culture and history, and there's a Trading Post next door.

Weekend handicrafts workshops and special events, such as storytelling in Ojibwe, are held year-round. A powwow is held on Memorial Day.

In the shores of Lake Vermilion in northeast Minnesota, near Tower, the Bois Forte Heritage Center includes exhibits on the history of the Ojibwe band.

© Beth Gauper

Near Green Bay, the Oneida Nation Museum, one of the nation's oldest Indian museums, includes a traditional Iroquois longhouse and exhibits, including one on Oneida warriors, who had seven commissioned officers in the Revolutionary War and have served in every U.S. military conflict since.

A gift shop sells contemporary Oneida and Iroquois arts.

In southwest Minnesota, the Jeffers Petroglyphs bear the story of an ancient people. Guides lead visitors along trails to see carvings of serpents, buffalo and stick figures, and the interpretive center holds programs on both ancient and modern Indian traditions.

For more, see Written in stone.

Farther west, rangers at Pipestone National Monument join visitors on the Circle Trail to talk about the cultural traditions surrounding the pipestone quarries, still used by members of Plains tribes.

In the Upper Midwest Indian Cultural Center, pipemakers and other artisans give demonstrations. It's open daily.

For more, see Pipestone homage.

Revisit the fur trade

On the shores of the Yellow River, near the St. Croix Ojibwe band headquarters in Hertel, Wis., Forts Folle Avoine Historical Park re-creates a fur post and Woodland Indian Village on the site of an 1802-1804 post.

Visitors can talk with interpreters on guided tours, Wednesday-Sunday from Memorial Day to Labor Day. Special events include the Great Folle Avoine Fur Trade Rendezvous in July.

© Beth Gauper

On the Snake River near Pine City, Minn., the re-created 1804 Snake River Fur Post includes an Ojibwe encampment, and interpreters portray the Ojibwe and metis who worked in the fur trade. Special events include Fall Gathering in September.

At the northeast tip of Minnesota, Grand Portage National Monument re-creates a fur depot at the site of the Kitchi Onigaming, the long portage around the Pigeon River first marked by Indian travelers.

It was the nerve center of the Great Lakes fur trade until 1803, when it was packed up and moved across the border to Thunder Bay. Costumed interpreters lead walking tours that include an Ojibwe encampment.

It's open daily from Memorial Day weekend to mid-October, and the year's biggest event is the Rendezvous and Powwow in August.

For more, see Life on the Grand Portage.

In Thunder Bay, Fort William Historical Park takes up where Grand Portage left off. It's a virtual Disneyland of the fur trade, with 42 buildings, including an Ojibwe encampment, and costumed interpreters who act the parts of real 1814 characters very convincingly.

© Beth Gauper

A full slate of demonstrations and dramas is held daily in July and August; the Anishnawbe Keeshigun cultural festival is in June.

For more, see Exploring Thunder Bay and Scenes from the fur trade.

Take a tour

Two self-guided tours allow people to learn more about two of the saddest episodes in U.S. history.

On the rolling byways of southwest Wisconsin, a series of roadside markers on the Black Hawk Trail recount the last leg of Sauk leader Black Hawk's flight from federal troops in 1832, which ended in the slaughter of his band, including many women, children and old men, on the Mississippi River.

In the Minnesota River Valley, many sites mark the events of the 1862 U.S.-Dakota War of 1862.

For more, see Mourning the summer of 1862 and River with a past.

On the way, don't miss the Treaty Site History Center in St. Peter, on the site where the Dakota gave up 24 million acres in 1851.

It contains fascinating exhibits on the characters of the era and shows copies of the "trader's papers" that claimed virtually all the money the Dakota received under 1851 and 1858 treaties. It's open Tuesday-Sunday from April through October.

Read more

Travel Wisconsin puts out a very good guide called Native Wisconsin, available free. Native American Tourism of Wisconsin also promotes heritage travel.

"Wisconsin Indians," by Nancy Oestreich Lurie, Wisconsin Historical Society Press, is a succinct summary of the convoluted history of Indians in that state, where official policies often played out first.

"Ojibwe Waasa Omaabodaa, We Look in All Directions," by Thomas Peacock and Marlene Wisuri, Afton Historical Society Press, is a beautifully illustrated book that includes a personal approach from author Peacock, a member of the Fond du Lac band of Ojibwe.

"American Indians: Answers to Today's Questions," by Jack Utter, University of Oklahoma Press, will be enlightening to anyone curious about Indians and their complex history.