Circling Lake Superior

A trip along its gorgeous shores provides everything a tourist's heart could desire.

© Beth Gauper

Of all the Great Lakes, Superior is the drama queen.

It's unpredictable and petulant, throwing tantrums that threaten to swallow any boat that ventures onto its waters. In 1975, it famously swallowed a boat that itself was called Queen of the Lakes.

Superior loves irony. The first recorded wreck, in 1816, was called the Invincible.

Everything about this lake is big and muscular. Volcanoes formed its shores, and hardened lava holds up dozens of waterfalls, except where giant dunes rise like shifting mountains.

It's fed by more than 200 rivers, which give it enough volume to cover all of North and South America with a foot of water. Its surface area is equal to Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Vermont and New Hampshire combined.

The Atlantic Ocean often is called the big pond. But Superior never is called anything so domestic — except teakettle, which always is paired with "tempest."

We adore this Great Lake. We can hardly stay away from it. It's beautiful, of course. And as our lifestyles become more sedentary, the lives of the first people on Superior — the explorers, the voyageurs, the lighthouse keepers and sailors — look that much more colorful and romantic.

Every year, thousands of people give the lake a big hug, following 1,300 miles of shoreline on the Circle Tour of Lake Superior.

Many stop to tour every lighthouse, see every waterfall and catch as many festivals as possible. For more, see Planning a Circle Tour.

Some only have a week off work to do it. For Circle Tour highlights on an eight-night, nine-day itinerary, see Lake Superior's greatest hits.

© Beth Gauper

Others have time to paddle out to islands and hike atop cliffs. Some photograph giant mascots and figures and learn their stories — Winnie-the-Pooh in White River, the goose in Wawa, Father Baraga in L'Anse, Terry Fox in Thunder Bay.

Nearly everyone stops at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum in Whitefish Point. Everyone should stop at Historic Fort William in Thunder Bay, a Disneyland of the fur trade.

But the Circle Tour also is for wanderers, for people who want to run beach pebbles through their fingers and swim in secluded coves and stop at kitschy roadside gift shops.

There's no wrong way to drive it, except too fast.

Heading east

The first time, I drove the Circle Tour clockwise in late June, celebrating Canada Day in Sault Ste. Marie in Ontario and the Fourth of July on Madeline Island in Wisconsin.

© Beth Gauper

The next time, my husband and I drove it counterclockwise in late July, starting in Duluth and making our first stop Bayfield, so we could see Big Top Chautauqua's musical revue "Keeper of the Light."

The nearby Apostle Islands have the nation's greatest concentration of National Park Service lighthouses, and no one is more revered than a lighthouse keeper.

But the tent revue is based on keepers' journals, so the story isn't so romantic.

"We work all night, or the ships sail blind," sings Peter Ivory, first assistant keeper at Outer Island in 1876. "There's enough darkness in a man, but my God, out here it stands up in your bones and roils your soul."

At the foot of Chequamegon Bay, we came to Ashland, where two local artists have spent a decade painting beautiful murals of Ashland's citizens — lighthouse keepers, lumberjacks, veterans. Now, there are more than 20 on the sides of downtown buildings.

It's easy to get waylaid in downtown Ashland — there's a great bakery, chocolatier, coffeehouse and food co-op that sells craft beers by the bottle — but we kept going.

On the Gogebic Range

Crossing into Michigan, we saw our first pasty shop, selling the hearty meat-and-potato pockets favored by miners.

We'd been to gorgeous Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park and hoped to go again soon, so instead we pushed on through Ottawa National Forest until we saw the double-decked vertical lift bridge in Houghton, which makes Duluth's bridge look like a Tinker Toy.

The only bridge over the 22-mile shipping canal that cuts the Keweenaw Peninsula in two, it's the widest and heaviest of its kind in the world.

Today, its lower deck is used for snowmobiles, and rainbow-colored sailboats have mostly replaced freighters filled with copper ore.

© Beth Gauper

Copper brought people to the Keweenaw, and when the mines closed, many people left.

Calumet was a company town — a plaque outside Washington School reads "From Minors to Miners" — but its chunky red-sandstone storefronts were built for posterity. The 1899 opera house, now the Calumet Theatre, still is a showcase for the arts.

We rejoined Lake Superior at Eagle River, where a sudden nor'easter claimed state geologist Douglass Houghton not long after his surveys jump-started the copper boom.

A narrow road took us past windswept beaches and through cedar forest to Copper Harbor. Access to the 1866 Copper Harbor Lighthouse is blocked by a private land owner, but you can visit if you rent a kayak.

Copper Harbor is at the end of U.S. 41 and the jumping-off spot for Isle Royale National Park, and in July, tourists fill its cafes and gift shops. But few venture to the quiet eastern side of the peninsula, where narrow beaches line the road.

© Beth Gauper

We pulled over and spent several hours on Oliver Bay, splashing over the shelves of smooth sandstone that lay under the water, in layers that looked just like cinnamon-vanilla swirl cake and were nearly as crumbly when poked with a toe.

Then we discovered ripe blueberries clinging to bushes covering the roadsides — and a young bear that also had discovered the blueberries and was too busy gobbling them to pay much attention to us.

A stay in a lighthouse

The Keweenaw is one of the few places in the north woods that's so remote developers leave it alone. Reluctantly, we drove on to Marquette, then northwest on a road that dead-ends at Big Bay Point Lighthouse, now a bed-and-breakfast.

There, we met lighthouse fans Steve and Judi Holland of Kalamazoo, Mich. They'd just visited Crisp Point Light, a 1904 beacon deep in forest west of Whitefish Point, at the end of 18 miles of bumpy road.

© Torsten Muller

"The first time, I got scared away, but then I came back," Steve Holland said. "Crisp is one of my favorite places. And Au Sable, I've gotta go back and see that."

They were doing the Circle Tour clockwise, heading for the lighthouses of Wisconsin and Minnesota, and we joked that we'd wave when our paths crossed again.

"We'll be in the red minivan; you can't miss us," Holland said with a smile.

We headed east to Marquette, where we took a spin around Marquette's Presque Isle Park, possibly the prettiest on the lake, and saw the redeveloped harbor front, where art installations and walking paths have replaced piles of coal.

In Munising, we took the glass-bottom boat shipwreck tour, passing the weathered Grand Island Harbor Light on our way to peer through the hull of the boat at splintered beams, toppled smokestacks, even a cast-iron commode.

© Beth Gauper

A lucky snafu

Munising is the headquarters of Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, and we'd planned to kayak along its colorful cliffs. But the outfitters said they had no record of my reservation and couldn't take us, which turned out to be a lucky thing.

Instead, we hiked the Chapel Loop atop the cliffs, which was spectacular, with a postcard panorama around every corner and one steep sand slide where we ran down for a cool dip in the lake.

We were worn out at the end of the 10-mile hike. Still, we drove east through miles of remote forest to the steep Log Slide of the Grand Sable Dunes, from which we could just spot the 1874 Au Sable Point Light, then onward to the funky little beach town of Grand Marais.

The next day we devoted to boats — big ones. At Whitefish Point, shipping lanes converge, visibility is poor and northwesters reach full fury, building up over 200 miles of open water.

Hundreds of wrecks lie near the point, earning it the title "Graveyard of the Great Lakes."

© Beth Gauper

The most famous wreck is the Edmund Fitzgerald, whose bell occupies an exalted spot in the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum. At the museum, we watched a short movie about shipwrecks whose opening and closing music was — what else? — "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald."

"I've only met Gordon Lightfoot once, but if I see him again, I'm going to strangle him," the elderly clerk told us, only half-joking.

On our way to Sault Ste. Marie, the halfway mark for people who start in Duluth, we stopped to climb the 1871 Point Iroquois Light. At the Soo Locks, we just missed the Mandarin, a Greek ship flagged in Cyprus.

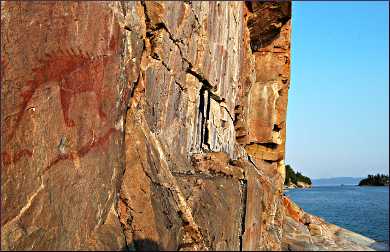

So we pushed into Ontario and made it to Lake Superior Provincial Park just as the rays of the setting sun were hitting Agawa Rock.

Long ago, Ojibwe lake travelers used a sheer cliff as a canvas for red ocher pictographs. There are paintings of canoes, serpents, a horse and a curious horned lynx with a spiked back and tail, believed to be Misshepezhieu, the water spirit.

© Beth Gauper

Some think the images depict a legendary battle, but they could simply be messages one traveler leaves to assist those who follow.

Climbing carefully, trying to avoid a sheer drop into the lake, we met Ojibwe-Pottawatomi artist Ken Tabobondung of Parry Sound, Ont., who had stopped to smoke a pipe in tribute.

"I like to think about when the ancestors came here, when it was natural," he said.

Superior's east coast

The scenery through which we traveled next — pine-studded islands, jagged red cliffs glittering with quartz, wild inland lakes and distant mountains — was jaw-dropping, and my husband spotted a moose along the road.

"This is crazy beautiful, and we're zipping right through it," he said. "This is better than the view from any lighthouse tower."

© Beth Gauper

But we were headed for the first really good meal of the trip, at Kinniwabi Pines in Wawa. Over plates of strawberry chicken and duck with black-currant sauce, we met Linda and Bruce Schlueter of Ramsey, Minn., who were doing the Circle Tour on a motorcycle and camping.

"These provincial parks are way incredible, much nicer than Minnesota state parks, and I love the Minnesota state parks," Linda Schlueter said. "You're going to be in heaven on Earth with what's coming up."

Wawa wasn't connected to the rest of the world until 1960, when the last section of the Trans-Canada Highway was laid there.

It's famous for its giant Canada goose — Wawa is Ojibwe for wild goose — and for Young's General Store, which sells pickles from a barrel and has a covered front porch with a stuffed moose and flush toilets in outhouses marked "Ma" and "Pa."

But Wawa also has a lovely, fiord-like lake, and we bought sandwiches and strawberry milk and had a picnic on its beach.

A chance meeting

Fog descended as we drove into Marathon, and it was drizzling when we got to Terrace Bay. Still, we made a detour to see Aguasabon Falls.

The four other people, in a red minivan, looked familiar. It was the Hollands, whom we'd last seen at Big Bay Lighthouse. From lighthouses, they said, they'd segued into waterfalls — Kakabeka near Thunder Bay, Rainbow near Rossport, then 100-foot Aguasabon Falls.

They told us they'd bought baked goods from the monks at the Jampot near Eagle River, toured Glensheen mansion in Duluth and spotted three bears in two separate places.

That day, they'd seen Ouimet and Eagle canyons and had a picnic on Nipigon Bay.

And they couldn't wait to see more.

"This is a beautiful, beautiful drive," Steve Holland said reverently.

© Beth Gauper

Judi Holland told us not to miss Rainbow Falls, but it was nearly 6 p.m. when we pulled up to the park office.

"Are you going to see any other provincial park today?" the young ranger asked us. "No? Well, there's a fee, but I don't see the point, so I'll let you in free."

The falls were running fast and furious, but so were the mosquitoes, so we ran for Rossport.

The next day was beautiful, and we went kayaking with a guide from Superior Outfitters. The Rossport Islands are a safer, closer-in version of the Apostles, ideal for beginning and intermediate kayakers.

I'd paddled the inner islands with the outfitters on the first trip and vowed to come back. This time, we paddled all the way to Battle Island, where the retired lighthouse keeper spends his summers.

Not only did he tell us stories, but he surprised our young guide by inviting us to climb into the 1911 red-and-white tower, from which we had a panoramic view from the catwalk.

© Beth Gauper

Tasty Thunder Bay

We straggled into Thunder Bay that evening. It's a great place to eat; we stopped for gelato in the Italian neighborhood, and had the famous Hoito pancakes in the Finnish neighborhood.

And of course we visited Historic Fort William, a reconstructed North West Co. fur post where living-history interpreters re-create 1815, often in dramatic vignettes that involve the conflicts that often arose.

In fact, we stayed until it closed, only then driving over to see famed Kakabeka Falls.

Then it was back over the border and a quick stop at Grand Portage National Monument, a re-creation of the British-owned North West post that had to be moved to Fort William in 1803.

The stretch of Minnesota 61 from the border to Duluth is a national scenic byway, and the scenery is spectacular and non-stop.

© Beth Gauper

You could easily spend a week or two just on this 150-mile stretch, and many do. There are agates to find, waterfalls to see, stones to skip, sweeping views to admire and hiking in seven state parks.

Grand Marais is a village of only 1,350, but it has everything a tourist could want and more, including a folk school, a craft brewery and a performing arts center.

The most-photographed place on the North Shore is Split Rock Lighthouse, and the most-visited is Gooseberry Falls State Park.

For the best view, drive up Palisade Head, just south of Silver Bay at Mile Marker 56.

There's a flame-red lighthouse and an ore dock to see in Two Harbors, and then you're back in busy Duluth — you could spend a whole week there, too.

It's hard to see everything on a Circle Tour; once is not enough. But as it turns out, twice isn't enough, either.

More about the Big Lake

It's an amazing lake, and here are some fun facts about it.

Here's a timeline of its history, starting at the end of the last Ice Age.